- Код статьи

- S032103910015606-9-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S032103910015606-9

- Тип публикации

- Статья

- Статус публикации

- Опубликовано

- Авторы

- Том/ Выпуск

- Том 81 / Выпуск 2

- Страницы

- 634-661

- Аннотация

Until recently the provenance of the offering basin known through the transcription in Urk. I, 165 remained uncertain. On the basis of a photograph from the George Andrew Reisner’s archive in the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston (Photo ID number: C10393_OS), it is possible to attribute to tomb G 1111 (Giza West Field). The present publication of the texts on the offering basin contains a number of corrections to the previous transcription by Kurt Sethe, as well as a commentary on the names and titles of the deceased and his son. Their names and titles show that both served as commanders of prospectors. A prosopography of all persons named jww-nmtj in the sources of the Old and Middle Kingdoms, as well as of the Old Kingdom holders of the office of sHD srjw “inspector of prospectors”, is compiled. In conclusion, it is suggested that the owner of the offering basin from tomb G 1111 is identical with jww-nmtj mentioned in inscription Sinai 13, which dates to the reign of Dd-kA-ra jzzj. This is currently the earliest date for a tomb in Cemetery G 1100 at Giza established through indirect synchronism.

- Ключевые слова

- Giza, Old Kingdom Egypt, Old Kingdom expeditions, Old Kingdom onomastics, Old Kingdom titles, Middle Kingdom onomastics

- Дата публикации

- 28.06.2021

- Год выхода

- 2021

- Всего подписок

- 11

- Всего просмотров

- 222

Tomb G 1111 is located in south-east area of the northern part of cemetery G 1100 within the Giza West Field necropolis which is immediately adjacent to Cheops Pyramid and is the largest cemetery at Giza.

According to architectural appearance, iconographic style of reliefs and statuary typologies, the earliest monuments of cemetery G 1100 date to the late 4th or early 5th Dynasties1; however, most of the tombs of this group belong to the category of the secondary construction dated to the 6th Dynasty. The evidence of titles does not make possible to identify any reliable criteria for dating tombs of this cemetery before the end of the 5th Dynasty.

Epigraphy of the group of tombs G 1100 is modest and for the most part is not published. Porter & Moss’ Topographical Bibliography provides only selected data on the tombs and monuments from this cemetery2:

- G 1104 (statue of zA=j-ms(.j)).

- G 1105 (statue Cairo JdE 377193).

- G 1109 (statue of mrt-jb=j).

- G 1111 (offering basin, data reported in Porter & Moss are incorrect; see further).

- G 1151 (the owner is nfr-qd=j).

- G 1152 (wooden statue of a boy, unnamed).

- G 1157 (unnamed statue).

- G 1171 (the owner is kA=j-m-Tnnt).

All the materials found in tombs of cemetery G 1100 are now available on websites www.gizapyramids.org and giza.fas.harvard.edu. Here one can find archive photos of monuments from other tombs of this cemetery as well as those that were found on its territory. The following epigraphical materials should be added to the body of information presented in the Topographical Bibliography:

G 1105 and G 1107 (false door of jHj, found in the debris between these tombs)4.

G 1107 (offering table for a group of people: smsw pr «elder of the house» nfr, mrtrt (indicator of nobility for ladies, exact meaning is uncertain) Spst, zS «scribe» wp, a woman named rwD-zAw=s, a man named prjw(?); it contains a dedication by Hm-kA «ka-servant» kAj)5.

- G 1119 (offering basin of jj-anx-n=f, see further).

- G 1123 (false door of tbAS)6.

- G 1152a (false door lintel of nj-kA=j-mjnw)7.

- G 1156 (false door of ptH-Htp)8.

- G 1162+1172 B (false door of ttj)9.

- G 1165 (offering basin of Tntj, see further).

- G 1177 (statue of kA=j-pw-ptH)10.

7. www.gizapyramids.org: B8584_NS.

8. www.gizapyramids.org: B7619_NS.

9. www.gizapyramids.org: C12034_OS; C11216_OS.

10. Cairo JdE 37716. Fischer 1960, 301–302, fig. 2; www.gizapyramids.org: B11753_OS; C11955_OS.

The bulk of attendants and officials buried at G 1100 cemetery were engaged in construction (G 1123, G 1105, G 1162+1172 B, G 1165) and organization of expeditions (G 1104, G 1111, G 1171). Two police titles (G 1171, G 1177), offices held in the corporation of xntjw-S (G 1151, G 1152a) and some others, for example, the juridical one (G 1156), are also mentioned. Inscriptions in their tombs contain only a few important indicators for their dating. Most notable is titulary of nfr-qd=j, the owner of tomb G 1151, who held the office of Hm-nTr ra m Szp(w)--ra «priest of Ra in the Sun temple Desire of the Sun»11. However, this title of a functionary in the cult of the Sun temple of king nj-wsr-ra cannot use as a reliable criterion for dating; according to other data tomb G 1151 should be dated later – to the second half of the 5th Dynasty12. Moreover, nfr-qd=j is the only known priest of Cheops (Hm-nTr xwfw) buried in cemetery G 1100.

12. Brovarski 2016, 86–87; cf. Nuzzolo 2018, 389–390 [74]: «Niuserre – Djedkare». A. M. Roth was inclined to identify him with nfr-qd=j, the owner of tomb G 2089 which she dated to the reigns of nj-wsr-ra – jzzj (Roth 1995, 94–95), however this dating is highly doubtful.

Inscriptions on the offering basin from tomb G 1111 provide an opportunity to specify the date of development of cemetery G 1100.

OFFERING BASIN FROM TOMB G 1111

First of all, it is necessary to once again clear up misunderstanding about attribution of offering basins Boston MFA 13.3282 and 13.3283 which finding place is sometime attributed to tomb G 111113. This is incorrect. According to data from the archive of G. A. Reisner, offering basin Boston MFA 13.3282 comes from G 1165 which belonged to Tntj14. jj-anx-n=f from tomb G 111915 was the owner of another offering basin, Boston MFA 13.3283.

14. Lehmann 1995, Taf. 24; www.mfa.org/collections/object/offering-slab-140858; www.gizapyramids.org: C11990_OS. Dating: 6th Dynasty. There was a misunderstanding, probably because of a mistake in manuscript by G. A. Reisner who specified G 1111 as a place of discovery of offering basin of Tjenti (G 1165): Reisner, G.A. A History of the Giza Necropolis III. 1942 (unpublished manuscript). [Chap.] 17: [Analytic Overview of] Cemetery G 1000–1600: [Pt.] 7: Chronology of Cemetery G 1000–1600. [Pt.] VII. P. 034 (giza.fas.harvard.edu/photos/63607/full/: UM2901). Appendix G: Cemetery G 1000–1100. P. 015 (giza.fas.harvard.edu/photos/63676/full/: UM2970).

15. www.gizapyramids.org: SC167191; see also: www.mfa.org/collections/object/offering-basin-of-iyankhenef-140860. Dating: late 6th Dynasty. The origin of the offering basin is also mentioned in Reisner’s documentation. Corrections of data from the PM III are presented on the website www.gizapyramids.org (Photo ID C11990_OS and SC167191) and on the website giza.fas.harvard.edu/sites/270/full/. See also Piacentini 2002a, 95, n. 3; 2002b, 334. The reading of the name as jj-anx=f is also likely.

According to documents from the archive of G. A. Reisner, another offering basin was found in G 1111 for which the following reference was made16: «Photo ID number: C10393_OS. Western Cemetery Giza; View: G 1111. Cemetery G «1100: G 1111, Photographer: George Andrew Reisner. Photo date: July 1904».

Photograph C10393_OS of the offering basin can be found on the websites www.gizapyramids.org and giza.fas.harvard.edu. Despite this publication, so far no one has paid attention to the offering basin, although this object is of interest for many reasons.

Epigraphy of the offering basin has long been available through K. Sethe’s transcription in Urk. I17. According to Sethe, the text was copied by W. Spiegelberg in 1907 from an object seen at an antiquities dealer at Giza. Sethe himself made a transcription after Spiegelberg’s estampage. The offering basin was entered into the Topographical Bibliography (Porter & Moss)18 with reference to Urk. I and, as a result, actually remained non-attributed. At present it is exclusively quoted according to publication in Urk. I19.

18. PM III.1 1974, 310.

19. For example, Wilson 1947, 240; Strudwick 2005, 245–246; Hannig 2003, passim.

According to the archive photograph C10393_OS, inscriptions on the offering basin from G 1111 basically correspond to the transcription published by Sethe in Urk. I, 165.

Thus, the offering basin was discovered by G. A. Reisner in July 1904, and already in 1907 it was seen by W. Spiegelberg at an antiquities dealer; that is within those three years the object was simply stolen from the excavation site at Giza or from the temporary storage and reach the antiquities market. I do not know the present location of this offering basin.

The photograph on the website www.gizapyramids.org clarifies Sethe’s reading of the inscriptions. Corrections relate only to reading the name in the inscription on the left side of the offering basin (line 3) and the final part of the offering formula. Besides that, the title before the name on the right side is not reproduced in Urk. I at all.

INSCRIPTIONS

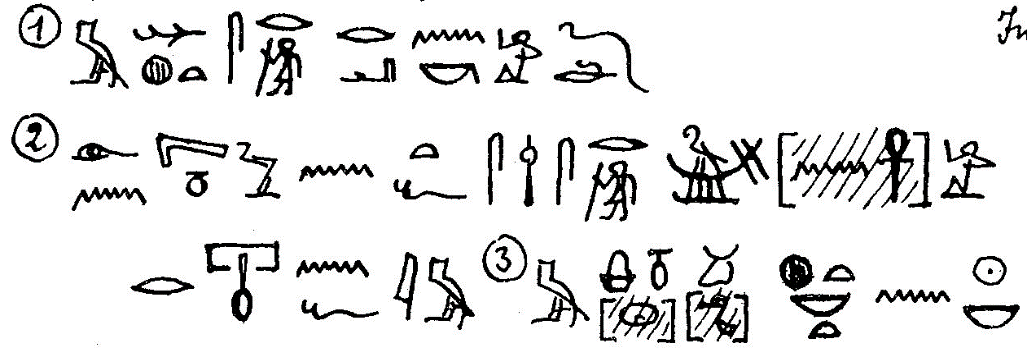

Transcription of the offering basin according to Urk. I, 165.4 and Urk. I, 165.8–10:

Note by K. Sethe: „a. So in einer andern Inschrift desselben Stei nes“.

Note by K. Sethe: „a. So in einer andern Inschrift desselben Stei nes“.

Transcription of the offering basin according to photograph C10393_OS published on the website www.gizapyramids.org :

| 1. Right side: |  |

| 2. Top: |  |

| 3. Left side: |  |

| 4. Bottom: |  |

| 1. sHD srjw nj-anx=j-nmtj | 1. Inspector of prospectors nj-anx=j-nmtj. |

| 2. jmj-xt srjw nj-kA=j-ra Dd(.j) | 2. Under-supervisor of prospectors nj-kA=j-ra says: |

| 3. jrj.n=j nw n jt=j sHD srjw [j]w(w)-nmtj (j)r pr(t) n=f xrw jm | 3. «I made this for my father, inspector of prospectors [j]w(w)-nmtj, that invocation offerings come forth for him therein, |

| 4. m t Hnqt kA [Apd] (j)xt nb(t) bnrt ra nb | 4. consisting of bread, beer, beef, [fowl], all sweet things every day». |

Commentary on the offering formula

Line 3. jrj.n=j nw n jt=j ... (j)r pr(t) n=f xrw jm «I made this for my father..., that invocation offerings come forth for him therein». One of the customary grammatical patterns of the formula prt-xrw «invocation offering» is presented here: in pseudo-verbal construction (j)r pr(t) xrw jm «that invocation offerings come forth therein»20. As it is known, this formula in the form sDm=f is represented by two patterns: prj=f xrw «he calls» (simple sDm=f, structure: «he comes forth by the voice») and Dj=f prj xrw «he calls» (structure: «he gives so that the voice would come forth» is, in this case, analytic, compound causative build on the pattern Dj=j rx=k «I inform you, I bring to your attention» which in Middle Egyptian was also used as subjunctive: «I would like to inform you; I have to tell you»21). In the first pattern the subject of «calling out» is a person while in the second pattern the voice itself is «coming forth». Such inversion of subjects of relationship for the verb prj «to come» is also reflected in the passive form sDm.tj=f: prj.tj xrw «(someone is) calling» (structure: «(someone is) coming out by the voice»). The formula in the infinitive pr(t) xrw is often used as a fixed expression which simply means «invocation, appeal» (to the deceased). Two directions of an action, however, still remain in its grammatical structure: it can be interpreted both as «coming forth by the voice» and as «coming forth of the voice». In our case the ritual appeal to the deceased is realized through inscriptions on the offering basin.

21. About this form, also attested in Old Egyptian, see Luft 1984, 103–111.

Line 4. (j)xt nb(t) bnrt ra nb «...all sweet things every day». For a long time, this phrase has been considered the only example of plene spelling of the word nbt «all, any» after jxt «thing» in combination (j)xt nb(t) «everything» that in the Old Kingdom always loses the ending -t in the word nb(t):  22

22 . Since this example was only written in Sethe’s transcription in Urk. I, 165.10, it has raised serious doubts23

. Since this example was only written in Sethe’s transcription in Urk. I, 165.10, it has raised serious doubts23 . The concerns proved justified: according to the photograph C10393_OS from Reisner archive, here isn't merely jxt nbt «everything», but the combination

. The concerns proved justified: according to the photograph C10393_OS from Reisner archive, here isn't merely jxt nbt «everything», but the combination  (j)xt nb(t) bnrt «all sweet things» which is well known from the formulae on other monuments24

(j)xt nb(t) bnrt «all sweet things» which is well known from the formulae on other monuments24; Kaplony 1963, 970 (1505); Lapp 1986, 134–138, 252 (§ 235–241); Hannig 2003, 203–205 {3691}, 422 {9875}; Daoud 2005, 140, pl. 70; Legros 2013, 154–155, 157 (g); Kanawati 2013, 351, fig. 2, 359, etc..png) . The feminine ending -t in Sethe’s transcription relates precisely to the word bnrt missed by him. Likewise, the preposition n in the transcription in Urk. I, 165.10 should be corrected to determinative pl. «3 grains» for the word bnrt «sweet».

. The feminine ending -t in Sethe’s transcription relates precisely to the word bnrt missed by him. Likewise, the preposition n in the transcription in Urk. I, 165.10 should be corrected to determinative pl. «3 grains» for the word bnrt «sweet».

Commentary on the names

Three names are mentioned on the offering basin: nj-anx=j-nmtj, [j]w(w)-nmtj and nj-kA=j-ra.

Following Sethe, the name of the deceased in the third line of the declaration is traditionally restored as [nj-anx]-nmtj based of the perfectly preserved name nj-anx=j-nmtj in the first line (the right side). Nevertheless, as a matter of fact, this name is to be read as [j]w(w)-nmtj, which does not preclude from assuming that named on the right-hand sHD srjw «overseer of prospectors» nj-anx=j-nmtj is still identical with him. Turns out the owner of the offering basin had two names with the element nmtj, the name of the god-wanderer, patron of travelers25.

Both anthroponyms with divine name nmtj as a component are rare26.

1. The name nj-anx=j-nmtj «my life belongs to the god nmtj» is built according to typical Old Egyptian pattern nj-anx=j-NN «my life belongs to (king or god) NN» or «NN owns my life». The following evidence of the name nj-anx=j-nmtj27 are mentioned in the literature:

1.1.  . False door Stockholm, Medelhavsmuseet, 1140628

. False door Stockholm, Medelhavsmuseet, 1140628. Dating: late 4th - early 5th Dynasty. Giza West Field..png) . Hypocoristic: nj29

. Hypocoristic: nj29 . Titles: jmj-rA mSa «general», rx nswt «king's acquaintance», [aD-mr grg]t mrr nb=f «[administrator of settlement], beloved by his lord», xrp wabw nswt Axt-[xwfw] «director of king's priests of the pyramid Horizon [of Cheops]». His eldest son and heir (zA=f smsw jwaw=f) jj-m-Htp had similar titles: sHD wjA «captain (of crew) of the ship», xrp (j)m(jw)-zA «director of the members of a phyle»30

. Titles: jmj-rA mSa «general», rx nswt «king's acquaintance», [aD-mr grg]t mrr nb=f «[administrator of settlement], beloved by his lord», xrp wabw nswt Axt-[xwfw] «director of king's priests of the pyramid Horizon [of Cheops]». His eldest son and heir (zA=f smsw jwaw=f) jj-m-Htp had similar titles: sHD wjA «captain (of crew) of the ship», xrp (j)m(jw)-zA «director of the members of a phyle»30 , aD-mr grgt «administrator of settlement», xrp wabw nswt «director of king's priests». According to the titles, both relatives served in the river fleet, organizing expeditions.

, aD-mr grgt «administrator of settlement», xrp wabw nswt «director of king's priests». According to the titles, both relatives served in the river fleet, organizing expeditions.

1.2.  . Relief Cairo CG 147931

. Relief Cairo CG 147931. Dating: late 4th Dynasty. On the dating the relief see also Diego Espinel 2014, 46–48 (late 4th - early 5th Dynasty)..png) . The example is doubtful as neither photograph nor the drawing of the inscription are published. This man was Hm-kA «funerary priest» of rn-(j)rj, father of leather worker wtA. H. Ranke read his name as nj-anx-zkr32

. The example is doubtful as neither photograph nor the drawing of the inscription are published. This man was Hm-kA «funerary priest» of rn-(j)rj, father of leather worker wtA. H. Ranke read his name as nj-anx-zkr32 . К. Scheele-Schweitzer gives a combined reading N(.j)-anx-Hn.w/Nm.tj «Besitzer von Leben ist die Hn.w-Barke/Nemti» with a note: «M.E. ist die Lesung als N(.j)-anx-Nm.tj hier zu bevorzugen»33

. К. Scheele-Schweitzer gives a combined reading N(.j)-anx-Hn.w/Nm.tj «Besitzer von Leben ist die Hn.w-Barke/Nemti» with a note: «M.E. ist die Lesung als N(.j)-anx-Nm.tj hier zu bevorzugen»33 . Doubts about the name reading are related to multiple meaning of sign

. Doubts about the name reading are related to multiple meaning of sign  given by L. Borchardt, which is open to different readings: nmtj, zkr, or Hnw «Sokar's boat»34

given by L. Borchardt, which is open to different readings: nmtj, zkr, or Hnw «Sokar's boat»34 . The reading nj-anx=j-zkr «my life belongs to Sokar»35

. The reading nj-anx=j-zkr «my life belongs to Sokar»35; Scheele-Schweitzer 2014, 424 [1564], 630 [2987] (?)..png) is based only on credence to Borchardt’s transcription; if it is right, then the sign is the ideographic name of the god Sokar. However, Sokar's name was not written with a single ideogram like Hnw, so nmtj is the preferred reading.

is based only on credence to Borchardt’s transcription; if it is right, then the sign is the ideographic name of the god Sokar. However, Sokar's name was not written with a single ideogram like Hnw, so nmtj is the preferred reading.

1.3. On the offering basin published in Urk. I, 165 which is the subject of this study.

Thus, there are only two reliable evidences for the name nj-anx=j-nmtj in the Old Kingdom, and one of them is preserved exactly on the offering basin from G 1111.

2. Name jww-nmtj occurs more often, it has been attested both in the Old36 and the Middle Kingdoms. By a strange coincidence it is not listed in H. Ranke’s Personennamen. Scheele-Schweitzer’s Handbuch cites the following data on this anthroponym:

2.1.  jww-nmtj. Inscription Hatnub Gr. 2.7 dating back to ttj37

jww-nmtj. Inscription Hatnub Gr. 2.7 dating back to ttj37 . Title: jmj-rA S «overseer of the lake (i. e. the contingent of soldiers and craftsmen and their locations)»38

. Title: jmj-rA S «overseer of the lake (i. e. the contingent of soldiers and craftsmen and their locations)»38 is also given here. However, previously published translation of this inscription (Osing 2004, 5) was not taken into account either by the publishers or me. Given the J. Osing’s article I made a new, slightly corrected translation, although it as well does not purport to be accurate until a quality publication appears: jmj-rA S rsj «overseer of the southern lake» kA=j-m-Tnnt(?), jmj-rA S rsj «overseer of the southern lake» xnzw-Htp, Xrj-a smntjw 260 (?) «under (their) supervision: 260 (?) guides» (only from photograph, transcription is missing), jmj-rA S mHtj «overseer of the northern lake» anx-m-a-ra, xrp apr S rsj «captain of a squad of the southern lake» nfr-sSm-ptH, zS S «scribe of the lake» mrw..png) . The reading of the name is doubtful. Hieratic original after G. Möller’s copy:

. The reading of the name is doubtful. Hieratic original after G. Möller’s copy:  .

.

2.2.  jww-nmtj. Inscription Hatnub Gr. 3.2 dated to «year of the 14th occasion (of the counting)» i. e. 27/28th regnal year of king Hr nTrj-xaw (ppj II)39

jww-nmtj. Inscription Hatnub Gr. 3.2 dated to «year of the 14th occasion (of the counting)» i. e. 27/28th regnal year of king Hr nTrj-xaw (ppj II)39 . Title: xtmtj-nTr «treasurer of the god». He was the expedition chief and the author of the inscription. His identity with the first jww-nmtj who lived under the reign of ttj is hardly possible as two graffiti are separated by 27 years.

. Title: xtmtj-nTr «treasurer of the god». He was the expedition chief and the author of the inscription. His identity with the first jww-nmtj who lived under the reign of ttj is hardly possible as two graffiti are separated by 27 years.

2.3.  jww-nmtj. Inscription in Wadi Maghara40

jww-nmtj. Inscription in Wadi Maghara40; <em>Urk</em>. I 1932–1933, 56.6–8; Gardiner, Peet, Černý 1952, pl. 7; Baines, Parkinson 1997, 9–27, fig.1; Tallet 2018, 304..png) . Title: jmj-rA sr(jw) «overseer of prospectors». It dates back to rnpt m-xt zp 4 Tnwt jHw awt nb «year after the 4th occasion of the counting all the large and small cattle», i. e. 8th/9th regnal year of king Dd-kA-ra jzzj.

. Title: jmj-rA sr(jw) «overseer of prospectors». It dates back to rnpt m-xt zp 4 Tnwt jHw awt nb «year after the 4th occasion of the counting all the large and small cattle», i. e. 8th/9th regnal year of king Dd-kA-ra jzzj.

2.4.  jww-nmtj. The name is attested on one or two figurines from the series of so-called Execration texts of the Old Kingdom41

jww-nmtj. The name is attested on one or two figurines from the series of so-called Execration texts of the Old Kingdom41, Taf. 42–43; Osing 1976a, 139 (RB 83), Taf. 44 (doubtful)..png) . Altogether, four pots with the Execration texts containing 435 names of rebellious Nubians and Egyptians (some of them duplicated) were discovered at Giza. Dating marks going back to year (m)-xt zp-5 «after the 5th occasion (of the counting)» i. e. to 10th/11th regnal year of unknown king remained on three pots, and namely:

. Altogether, four pots with the Execration texts containing 435 names of rebellious Nubians and Egyptians (some of them duplicated) were discovered at Giza. Dating marks going back to year (m)-xt zp-5 «after the 5th occasion (of the counting)» i. e. to 10th/11th regnal year of unknown king remained on three pots, and namely:

1. Pot of series AB: (m)-xt zp 5 Abd 3 prt hrw 29 «year after the 5th occasion (of the counting), 3rd month of the seed season, 29th day»42;

2. Pot of series J: (m)-xt zp-5 Abd 3 prt hrw 22 «year after the 5th occasion (of the counting), 3rd month of the seed season, 22nd day»43;

3. Pot of series RK: (m)-xt zp 5 Abd 2 prt hrw 5 «year after the 5th occasion (of the counting), 2nd month of the seed season, 5th day»44.

According to these data the ritual, in the course of which the pots were buried, lasted over 55 days (from at least Abd 2 prt hrw 5 «5th day of 2nd month of the seed season» to Abd 3 prt hrw 29 «29th day of 3rd month of the seed season»). I think that burial of the figurines with the names of Nubian rebels at Giza was the result of the punitive campaign of king mrj.n-ra to Nubia which was accomplished in his 9th/10th regnal year. Campaign rock inscriptions, devoted to that event, contain the following dates from the reign of mrj.n-ra45: zp 5 Tnwt Abd 2 Smw hrw 24 «year of the 5th occasion of the counting, 2nd month of the harvest season, 25th day»46, and zp 5 Tnwt Abd 2 Smw hrw 28 «year of the 5th occasion of the counting, 2nd month of the harvest season, 28th day»47. If one accepts dating of the figurines with the Execration texts to the reign of mrj.n-ra, that means that they were made 6-8 months later than the above-mentioned graffiti48. During that period of time (between 2nd month of the harvest season of year of the 5th occasion of the counting and 2nd month of the seed season of year after the 5th occasion of the counting) king mrj.n-ra reached Nubia, defeated rebels, drew up a list of those who had been slain or executed, came back and performed the rite of burying the pots with the figurines of the rebels at Giza. The name jww-nmtj is typical exactly for the expedition members; thus, that military man or prospector repeatedly visited Nubia in the line of duty. Most of the rebels, listed on the occasion of their rebellion suppression, had Nubian names49, and only a few dozen held Egyptian names50, at that Nubians with Egyptian names were singled out as a special group since they were clarified by the title nHsj «Nubian»51, though not always. Some persons were of the mixed descent52 which attests to the long-term contacts between Egyptians and Nubians. This impressive union of Nubians and Egyptians was in vassal dependence on Egypt for a long period of time, however for unknown reasons they rose in rebellion at the end of the reign of mrj.n-ra. Egyptian jww-nmtj probably was a member of the expeditionary contingent in Nubia that became involved in the native rebellion and paid for that.

46. Kaiser et al. 1976, 79; Seidlmayer 2005, 290–291, Anm. 11, Taf. 6b. Rock niche of the temple of Satet on Elephantine Island. The name of king nfr-kA-ra without indication of the regnal year is also attested herein.

47. Urk. I 1932–1933, 110.10–16. Island of Hesse, the First Cataract of the Nile.

48. Inscription Hatnub VI (Anthes 1928, 14, Taf. 5 = Urk. I 1932–1933, 256.18) also dates to the year after the 5th occasion of the counting (10th/11th regnal year) of mrj.n-ra.

49. Osing 1976a, 160–164.

50. Osing 1976a, 158–159, 164.

51. Osing 1976a, 159–160. Remarkable example: leader («foreign ruler», HqA-xAst) of all rebels had the Egyptian name anx-wnjs «wnjs will live»; his Nubian name was jAtrAs (Abu Bakr, Osing 1973, 112–113 [199], Taf. 52-53).

52. This fact is established by the filiation data: Osing 1976a, 160.

This list of holders of the name jww-nmtj should be supplemented with the data collected by Michelle Thirion53:

2.5.  jww-nmtj. A gift bearer with the title smr «courtier»54

jww-nmtj. A gift bearer with the title smr «courtier»54 .

.

2.6.  jww-nmtj. Statue Liverpool, World Museum, 1967.455

jww-nmtj. Statue Liverpool, World Museum, 1967.455; www.liverpoolmuseums.org.uk/artifact/statue-of-sobekhotep (unsatisfactory photographs). Ihnasiya el-Medina. Dating: late Old Kingdom - beginning of the First Intermediate Period..png) . He held the office of jmj-rA st xntjw-S pr-aA «overseer of the bureau of the palace attendants» and was the son of the statue owner, jmj-rA mSa «military commander» and jmj-jrtj «captain» sbk-Htp, who also held the ritual title jmAxw xr nmtj «revered with nmtj»56

. He held the office of jmj-rA st xntjw-S pr-aA «overseer of the bureau of the palace attendants» and was the son of the statue owner, jmj-rA mSa «military commander» and jmj-jrtj «captain» sbk-Htp, who also held the ritual title jmAxw xr nmtj «revered with nmtj»56, 28–29 (132–134); a Middle Kingdom ritual title jmAxw xr nmtj nb Atft «revered with nmtj – lord of the 12th nome of Upper Egypt» is also known (Fischer 1974, 19 (fig. 21), 21–22 (fig. 29), 25–26 (fig. 24)). About the god nmtj nb Atft «nmtj - lord of the 12th nome of Upper Egypt» on private monuments up to the 18th Dynasty see also Abdel-Raziq 2017, 3–8, fig. 1–2..png) . According to this title, both of them were natives of the 18th (Sharuna – el-Kom el-Ahmar/Sawaris)57

. According to this title, both of them were natives of the 18th (Sharuna – el-Kom el-Ahmar/Sawaris)57 , 12th (Deir el-Gebrawi – El-Atawla) or 10th nomes of Upper Egypt where the cult of the god nmtj was practiced. Another son of sbk-Htp, also named sbk-Htp, was jmAxw xr st-jrt nb Ddw jnpw nb spA nmtj nb Tbt «revered with Osiris lord of Busiris, Anubis lord of Sepa, and Nemty lord of Qau». If my reading of the settlement name as

, 12th (Deir el-Gebrawi – El-Atawla) or 10th nomes of Upper Egypt where the cult of the god nmtj was practiced. Another son of sbk-Htp, also named sbk-Htp, was jmAxw xr st-jrt nb Ddw jnpw nb spA nmtj nb Tbt «revered with Osiris lord of Busiris, Anubis lord of Sepa, and Nemty lord of Qau». If my reading of the settlement name as  Tbt «bottoms of the feet» (having in mind the cut off clows of the god nmtj) is correct, then it is the first occurrence of the name of the city Antaeopolis (Tbw), and it is about that the god nmtj which cult localized in the 10th nome of Upper Egypt.

Tbt «bottoms of the feet» (having in mind the cut off clows of the god nmtj) is correct, then it is the first occurrence of the name of the city Antaeopolis (Tbw), and it is about that the god nmtj which cult localized in the 10th nome of Upper Egypt.

2.7.  jw(w)-nmtj-wr{t}58

jw(w)-nmtj-wr{t}58. Abydos. Dating: late 13th Dynasty. The major part of the inscriptions on the stela were made in hieratic script..png) . This masculine name is sometimes read as jwt-nmtj or nmtj-jwt59

. This masculine name is sometimes read as jwt-nmtj or nmtj-jwt59 , however, judging from the photograph, it should be exactly read as jw(w)-nmtj-wr{t}, i. e. jw(w)-nmtj Elder (with the false feminization of the epithet wr «Elder» because of a mistake made when transferring the hieratic text into stone60

, however, judging from the photograph, it should be exactly read as jw(w)-nmtj-wr{t}, i. e. jw(w)-nmtj Elder (with the false feminization of the epithet wr «Elder» because of a mistake made when transferring the hieratic text into stone60 compare example of the masculine name jtj=sn-nDs{t} (Moussa 1972, 290, Taf. 29). However, in this case the epithet wr «Elder» was used rather than nDs «Junior»..png) ). This person is shown in the bottom register of the stela: his name was chiseled while several columns of the text, preceding it, were written in ink – nowadays, these inscriptions are completely lost. Name and title of the owner of the stela are written on the top in a mixture of hieratic and ideographic script, and the ideographic inscription on the arch of the stela changes the writing direction and the order of signs several times. The owner held the office of jmj-rA zA n Xrtjw-nTr «overseer of a phyle of the craftsmen of the necropolis», and his name is probably also to be read jw(w)-nmtj-wr. If this is so, then the owner was depicted on the stela two times. The boy with the title zA=s «her son», standing behind the mother, also bears the name in honor of the god nmtj: nmtj-nxt. Such propensity of the family for the cult of the god nmtj makes it possible to assume that it originated from the 13th or 18th nome of Upper Egypt.

). This person is shown in the bottom register of the stela: his name was chiseled while several columns of the text, preceding it, were written in ink – nowadays, these inscriptions are completely lost. Name and title of the owner of the stela are written on the top in a mixture of hieratic and ideographic script, and the ideographic inscription on the arch of the stela changes the writing direction and the order of signs several times. The owner held the office of jmj-rA zA n Xrtjw-nTr «overseer of a phyle of the craftsmen of the necropolis», and his name is probably also to be read jw(w)-nmtj-wr. If this is so, then the owner was depicted on the stela two times. The boy with the title zA=s «her son», standing behind the mother, also bears the name in honor of the god nmtj: nmtj-nxt. Such propensity of the family for the cult of the god nmtj makes it possible to assume that it originated from the 13th or 18th nome of Upper Egypt.

Several other names should be added to these data:

2.8.  jww-nmtj. Graffito in Gebel Abrak (Eastern Desert)61

jww-nmtj. Graffito in Gebel Abrak (Eastern Desert)61..png) . Title: jmj-rA 10 srjw smntjw «overseer of the ten prospectors and guides»62

. Title: jmj-rA 10 srjw smntjw «overseer of the ten prospectors and guides»62 is implausible (cf. de Bruyn 1958, 97; Eichler 1993, 91 (188); Jones 2000, 218 (814)) since the title jmj-rA zSw «overseer of scribes» is not used without specifying the name of the department. For the reading see also Fischer 1985, 31, n. 24..png) .

.

2.9.1.  jw(w)-nmtj63

jw(w)-nmtj63); formerly Guimet C 13: Moret 1909, 29–31, pl. 12 (13); <a target=_blank href=)

, however the name jw(w)-nmtj with the same scriptio plena Berlev read simply as nmtj, although the sign «legs»

, however the name jw(w)-nmtj with the same scriptio plena Berlev read simply as nmtj, although the sign «legs»  in it is obvious:

in it is obvious:  .

.

2.9.2–3. The name jw(w)-nmtj in the similar form  was also attested on stelae Cairo CG 20520 (masc.)65

was also attested on stelae Cairo CG 20520 (masc.)65. Abydos..png) and Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional, 627 [2419] (fem.)66

and Rio de Janeiro, Museu Nacional, 627 [2419] (fem.)66; Kitchen 1990, I, 16–17; II, pl. 1–2 (1), with a mistake in the transcription of the name. Abydos..png) . This name was included in Ranke’s Personennamen as an alternative to the simple name nmtj in scriptio plena67

. This name was included in Ranke’s Personennamen as an alternative to the simple name nmtj in scriptio plena67 (Adams 2010, 5–7, fig. 4–5).]]]. The name nmtj without the ‘falcon on a boat’ ideogram on the other stelae should also be understood as the divine name nmtj adopted as the personal name68

(Adams 2010, 5–7, fig. 4–5).]]]. The name nmtj without the ‘falcon on a boat’ ideogram on the other stelae should also be understood as the divine name nmtj adopted as the personal name68 without any epithet appeared in the Middle Kingdom. The Old Kingdom names xnsw (fem.) and Xnmw=j/Xnmt=j are not related to the gods xnzw and Xnmw respectively (another reading: Scheele-Schweitzer 2014, 603 [2783], 615–616 [2861]–[2863])..png) considering to the parallels on the other stelae or to the names of the relatives (for example, the name nmtj-Htp on stela Cairo CG 2060569

considering to the parallels on the other stelae or to the names of the relatives (for example, the name nmtj-Htp on stela Cairo CG 2060569 , nmtj-wr on stela Cairo CG 2052070

, nmtj-wr on stela Cairo CG 2052070 ) on stela Cairo CG 20520 and jmj-rA pr «householder» nmtj-wr (

) on stela Cairo CG 20520 and jmj-rA pr «householder» nmtj-wr ( ) on stela Leiden, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, L.XI.2 (Leiden V 108: Boeser 1909, 13 [50], Taf. 38; Simpson 1974, pl. 16 (ANOC 7.2) are apparently the same person (Franke 1984, 217 (325)).]]], Antaeopolite names on stela Cairo CG 2059171

) on stela Leiden, Rijksmuseum van Oudheden, L.XI.2 (Leiden V 108: Boeser 1909, 13 [50], Taf. 38; Simpson 1974, pl. 16 (ANOC 7.2) are apparently the same person (Franke 1984, 217 (325)).]]], Antaeopolite names on stela Cairo CG 2059171 ). This is why the sign «legs»

). This is why the sign «legs»  could also not be the determinative for the hypothetic name nmtj «wanderer» from the verb nmt «walk, wander»: the name nmtj always meant only the god-wanderer. Although, on rare occasions, the divine name nmtj is presented only by the ideogram «legs» with the phonetic complements (

could also not be the determinative for the hypothetic name nmtj «wanderer» from the verb nmt «walk, wander»: the name nmtj always meant only the god-wanderer. Although, on rare occasions, the divine name nmtj is presented only by the ideogram «legs» with the phonetic complements ( )72

)72 , the sign

, the sign  after the ideogram of the falcon-god on a boat was not reliably attested. In this regard, I distinguish the name

after the ideogram of the falcon-god on a boat was not reliably attested. In this regard, I distinguish the name  from the simple name nmtj in scriptio plena and read it as jw(w)-nmtj despite the fact that the element jw(w) is presented in it as a single sign “legs”, i. e. in the form which does not occur in the full variants of the name jw(w)-nmtj.

from the simple name nmtj in scriptio plena and read it as jw(w)-nmtj despite the fact that the element jw(w) is presented in it as a single sign “legs”, i. e. in the form which does not occur in the full variants of the name jw(w)-nmtj.

2.10.  jww-nmtj-wr (т.е. jww-nmtj Elder). Stela Sinai 8573

jww-nmtj-wr (т.е. jww-nmtj Elder). Stela Sinai 8573 .

.

Spelling the name in inscriptions Abrak (2.8) and Sinai 85 (2.10) is of interest. In the first case the writer violated the rule of pronouncing the divine name honoris causa, in the second case the component jww is presented in the full form. Thus, it is necessary to read the name as jww-nmtj «coming of nmtj» where jww is nomen actionis from the verb jwj «come». The word jww «coming»74 means the child himself who impersonated «appearance» (of a certain god) before the father.

The reading of the name as jww-nmtj is confirmed by several examples of the names from the Old and the Middle Kingdoms that were formed on the similar principle - with the initial nomen actionis from the verb jwj «come». This pattern coexisted with the similar derivatives in the form sDm=f or with a pseudo-participle from the verb jwj. The following examples of the names with nomen actionis jww/jwt «coming» can be found in the anthroponymy of the Old and the Middle Kingdoms:

1.  jww-bA «coming of the sacred Ram»75

jww-bA «coming of the sacred Ram»75.w-BA «kommend ist der (heilige) Bock»; Gundacker 2013, 45: Jwjw-Bt «Bata soll kommen!»; Gundacker 2014, 67: Jwjw-BA «Der heilige Bock soll kommen!»..png) . Double waw indicates the form nomen actionis from the verb jwj «come».

. Double waw indicates the form nomen actionis from the verb jwj «come».

2. jww-bnw «coming of phoenix». Two individuals are known who have that name attested in the different spelling: 1)  76

76 and 2)

and 2)  77

77. For reading the name cf. Ranke 1935, 97.10; 1952, 277.10; Schindler von Wallenstern 2011, 231..png) .

.

3.  jww-ptH. This name in the form nomen actionis is mentioned on a stela of the First Intermediate Period78

jww-ptH. This name in the form nomen actionis is mentioned on a stela of the First Intermediate Period78 (Bosticco 1959, 22, fig. 15 (15); Fischer 1964, 80–81, pl. 24 (27). Naqada). Cf. Ranke 1935, 138.12..png) . A similar name, but in a different form, is attested in the Second Intermediate Period:

. A similar name, but in a different form, is attested in the Second Intermediate Period:  ptH-jw.j where jw.j is a pseudo-participle79

ptH-jw.j where jw.j is a pseudo-participle79. Edfu). Cf. stela Aix-en-Provence, Musée Granet, 849.1.367 (<em>PM</em> VIII.1 1999, 91: (803-027-141); Barbotin 2020, 56–59 (7). Abydos (?)) where the name of the same pattern but with a different spelling is attested: image32.png) with the reading ptH-jw.j.]]].

with the reading ptH-jw.j.]]].

4.  jwt-n=j-ptH «coming of Ptah to me» masc.80

jwt-n=j-ptH «coming of Ptah to me» masc.80 where the word jwt «coming» (in the feminine gender) was formed according to another model of nomen actionis81

where the word jwt «coming» (in the feminine gender) was formed according to another model of nomen actionis81. Cf. the name in sDm=f form, with the same meaning: ptH-jw(j)=f-n=j «Ptah, he came to me» (Scheele-Schweitzer 2014, 362 [1146])..png) .

.

5.  jw(w)-n=j-sbk «coming of Sobek to me»82

jw(w)-n=j-sbk «coming of Sobek to me»82 where the word jww «coming» is nomen actionis with the w-ending as in the name jww-nmtj83

where the word jww «coming» is nomen actionis with the w-ending as in the name jww-nmtj83mj-n=j-Cbkw «Komm zu mir, Sobek!» (m.). I interpret the grammatical form of the similar examples given in Gundacker 2010, 70: Ex. (53, dwA-n=j-Raw), Ex. (54, Hsj-n=j-PtH), and Ex. (55, jAj-n=j-PtH)) as the perfective relative form. It is difficult to translate these names, though the common content is approximately like the following: dwA.n-ra «the one who (came) by the grace of Ra» («begged for from the Sun»), Hzj.n-ra «the one who (came) by the grace of Ra» («blessed by the Sun»; it is worth noting that the verb Hzj «favor, praise,<strong> </strong>reward» always expresses action of a lord with respect to a subordinate or a father to his son, and not vice versa) and jAj.n-ptH «the one who came through prayer to Ptah» («begged for from Ptah»). Analogues of these names with a participium perfecti passivi (i. e. without n) and with the same meaning are also known: dwA-ra (cf. Scheele-Schweitzer 2014, 743 [3770]: «der Re preist»), Hzj-ra (cf. Scheele-Schweitzer 2014, 554 [2510]: «Gelobter des Re»), jAjw-ptH (cf. Scheele-Schweitzer 2014, 207 [61]: «Verehrer des Ptah»)..png) . Nomen actionis is used in the names No. 4 and 5 instead of the simple sDm=f form (as in the name pattern jj-n=j-NN «NN came to me»84

. Nomen actionis is used in the names No. 4 and 5 instead of the simple sDm=f form (as in the name pattern jj-n=j-NN «NN came to me»84 ).

).

6.  jww-wp(j)-wAwt «coming of Wepwawet», he is also known by the name nfr-jww «good coming» which his father also held85

jww-wp(j)-wAwt «coming of Wepwawet», he is also known by the name nfr-jww «good coming» which his father also held85. Abydos. Dating: 13th Dynasty..png) . The variant nfr-jww with the epithet nfr «good» confirms the meaning of the word jww «coming» as nomen actionis once more. The Middle Kingdom names of this type with the element nfr were divided into two patterns: nfr-jww86

. The variant nfr-jww with the epithet nfr «good» confirms the meaning of the word jww «coming» as nomen actionis once more. The Middle Kingdom names of this type with the element nfr were divided into two patterns: nfr-jww86 and jww-nfr «good coming»87

and jww-nfr «good coming»87 , to which adjoined the name jww-nfrt «coming of the beauty»88

, to which adjoined the name jww-nfrt «coming of the beauty»88 . The name jww-nfr/ nfr-jww occurs dozens of times in the Middle Kingdom, both for men and women. On the contrary, the equally widespread name jww-nfrt occurs only for women and only in the Middle Kingdom. Its Old Kingdom prototype nfrt-jww=s «beauty, (this is) her coming»89

. The name jww-nfr/ nfr-jww occurs dozens of times in the Middle Kingdom, both for men and women. On the contrary, the equally widespread name jww-nfrt occurs only for women and only in the Middle Kingdom. Its Old Kingdom prototype nfrt-jww=s «beauty, (this is) her coming»89 gives more reason to see the goddess Hathor in this «beauty». This explains the constant carrying forward the word nfrt «beauty» in the Middle Kingdom name jww-nfrt whereas position of the verb nfr «be good» in the name jww-nfr/ nfr-jww is not stable; thus, the name patterns of jww-nfr/ nfr-jww (masc./fem.) and jww-nfrt (only fem.) are not equivalent. The name pattern with pseudo-participle nfrt-jj.tj «the beauty is coming» (Nefertiti) on the Middle Kingdom material is not attested. In this name, as before, Hathor is the deity who is hiding under the name nfrt «beauty»90

gives more reason to see the goddess Hathor in this «beauty». This explains the constant carrying forward the word nfrt «beauty» in the Middle Kingdom name jww-nfrt whereas position of the verb nfr «be good» in the name jww-nfr/ nfr-jww is not stable; thus, the name patterns of jww-nfr/ nfr-jww (masc./fem.) and jww-nfrt (only fem.) are not equivalent. The name pattern with pseudo-participle nfrt-jj.tj «the beauty is coming» (Nefertiti) on the Middle Kingdom material is not attested. In this name, as before, Hathor is the deity who is hiding under the name nfrt «beauty»90 , which appeared during the 18th Dynasty and survived into the Ptolemaic period (also in the form tA-nfr(t)-jj.tj).

, which appeared during the 18th Dynasty and survived into the Ptolemaic period (also in the form tA-nfr(t)-jj.tj).

7.  nfr-jww-Hwt-Hr «coming of Hathor is good»91

nfr-jww-Hwt-Hr «coming of Hathor is good»91 «gut ist, daß Hathor kommt»; Gundacker 2014, 96, Ex. (109): «Vollkommen ist, daß Hathor kommt!»..png) . The female name in which jww «coming» can be understood only as nomen actionis.

. The female name in which jww «coming» can be understood only as nomen actionis.

A compound name jmn-m-HAt-nfr-jw(w)92 is also known, however in this case nfr-jw(w) is only the second name of the man93.

93. Vernus 1971, 196 (13); Vernus 1986, 8 (19).

The feminine names  Hwt-Hr-jw(j).t(j) «Hathor is coming»94

Hwt-Hr-jw(j).t(j) «Hathor is coming»94 and

and  sxt-jw(j).t(j) «Sekhet (Field-goddess) is coming»95

sxt-jw(j).t(j) «Sekhet (Field-goddess) is coming»95 should be considered as pseudo-participial constructions, built according to a name pattern with the masculine subject kA=j-jw(j.j)/ kA=j-jw(j).w «my Ka is coming», with the element kA in the initial position96

should be considered as pseudo-participial constructions, built according to a name pattern with the masculine subject kA=j-jw(j.j)/ kA=j-jw(j).w «my Ka is coming», with the element kA in the initial position96.w is an example of existence of the pseudo-participial ending .w for the verb jj/jwj «come» already in Old Egyptian (cf. Edel 1955–1964, 272, § 573; 278, § 579), which further demonstrates the diatopic character of divergence between the pseudo-participial forms, with the endings .j and .w, as well without any ending in Egyptian language. Cf. the names jj-kA=j «my <em>Ka</em> came» and jj-kAw=j «my <em>Kau</em> came» in the form sDm=f (Scheele-Schweitzer 2014, 216–217 [124]–[126])..png) . Generally, the sign «legs» in the name Hwt-Hr-jj.tj / Hwt-Hr-jw(j).tj97

. Generally, the sign «legs» in the name Hwt-Hr-jj.tj / Hwt-Hr-jw(j).tj97. To add: <em>1)</em> stela Louvre E 27211 (Ziegler 1990, 74–77 (8); <em>2)</em> inscription Kumma 452 = Khartoum, Sudan National Museum 34381 (Hintze, Reineke 1989, I, 127; II, Taf. 172); <em>3)</em> stela Langres 110 (Gauthier-Laurent 1931, 110–111, pl. 1); <em>4)</em> statue Dahshur Magazine 160 (Fakhry 1961, 20, fig. 295, pl. 57A; Schulz 1992, I, 128–129 (053); II, Taf. 22c); <em>5)</em> stela Moscow, The Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts I.1.a.1136 (Hodjash, Berlev 1982, 86–87 (40)); <em>6)</em> stela Cairo CG 20656 (Lange, Schäfer 1902b, Taf. 50; 1908, 289; Stefanović 2011, 98, 100); <em>7)</em> stela Cairo CG 20228 (Lange, Schäfer 1902a, 248; 1902b, Taf. 17). All the examples date to the Middle Kingdom and the Second Intermediate Period..png) was made purposely more complicated to the sign jj (

was made purposely more complicated to the sign jj ( ), since in the name form jww/jwt «coming» this sign was never used, only the sign jw (

), since in the name form jww/jwt «coming» this sign was never used, only the sign jw ( ); on the contrary, this simple sign jw (

); on the contrary, this simple sign jw ( ) was sometimes used to form a pseudo-participle - for example, the name Hwt-Hr-jw(j).tj «Hathor is coming» on stela Louvre C 11198

) was sometimes used to form a pseudo-participle - for example, the name Hwt-Hr-jw(j).tj «Hathor is coming» on stela Louvre C 11198

. Thus, the pseudo-participle from the verb jwj in this name is presented in two forms: jj.tj and jw(j).tj «she is coming» which also occurs in other names.

. Thus, the pseudo-participle from the verb jwj in this name is presented in two forms: jj.tj and jw(j).tj «she is coming» which also occurs in other names.

Taking into account the anthroponymic material, military officers, expedition members and travelers often held the name jww-nmtj which indicated that they followed footsteps of their fathers who served in the same professional sphere. A separate group is made up of those born in the 10th, 12th or 18th nomes of Upper Egypt (Nos. 2.6, 2.7, 2.9.1-2, 3(?)) who got their names with the component nmtj out of reverence for the local god of their nomes, the Falcon on a boat.

3. Author of the inscription on the offering basin, son of jww-nmtj, had the name nj-kA=j-ra «my Ka belongs to Ra».

This name was fairly common in the Old Kingdom. Scheele-Schweitzer’s Handbuch provides data about eight bearers of this name99. Besides them, the following persons are known:

3.1. Spsj nswt jmj-rA qdw «king's nobleman, overseer of builders» nj-kA=j-ra, father of jmAx(w)t «revered» TTj100. His correspondence to sHD qdw, sHD Hmw-kA «inspector of builders, inspector of funerary priests» nj-kA=j-ra, a servant of jj-mrj, owner of tomb G 6020101, remains questionable since presence of the title Spsj nswt «king's nobleman» for nj-kA=j-ra on the offering basin is a clear evidence in favour of dating to at least the reign of ttj while usually tomb G 6020 (jj-mrj) is reasonably dated to the first half of the 5th Dynasty.

101. Weeks 1994, 51, fig. 42 {2.120}.

3.2. nj-kA=j-ra, son of xaj-mrr-nbtj, grandson of xwfw-snb and Hnwt=sn102.

Commentary on the titles

Two titles from the sphere of the organization of expeditions are attested on the offering basin:

1. nj-kA=j-ra: jmj-xt srjw «under-supervisor of prospectors».

2. nj-anx=j-nmtj / jww-nmtj: sHD srjw «inspector of prospectors».

Range of problems connected with interpretation of the lexical item srj «presage, forecast, predict» etc.103 Social designations from the sphere of lexicography of srj deserve a separate study; this is why for the present I limit myself to categorical conclusions on the initial results of my own study which hopefully shall be completed soon.

Considering the meaning of the word sr(j) «official, office-holder»104, many scholars interpreted the term sr(j)w in the expedition titles as «officials»105. However, it should be noted that actually the office sr(j) «official» did not existed in the Old Kingdom. The term sr(j) in Old Egyptian was used in the meaning derived from the verb «envisage», however with many nuances depending on occupation of the holder: «auditor, controller, agent, informer, scout». In most of the narrative contexts (i. e. outside the titulary) it appeared as a general notion sr(j) «official» with the non-determined content. The title sr(j) transformed into a functional office only in the expedition nomenclature where to it was included with the meaning «geological explorer, prospector». It occurs mostly in the hierarchical titles jmj-rA sr(j)w / sHD sr(j)w «overseer / inspector of prospectors».

105. Goelet 1982, 200–201 (n. 199); Fischer 1985, 31; Eichler 1993, 169; Martin-Pardey 1994, 159–160, 162; Moreno García 1997, 108; Jones 2000, 229–230 (849–851), 909 (3331–3335), 966–967 (3564–3565), et al.

The contingents of srjw often appear in the titles together with the crew of smntjw which is indicative of resemblance of their functions. And because smntjw are usually determined as «guides»106, then for the title srjw a suitable equivalent is «prospectors»; it is derived from the verb sr(j) in the meaning «survey the routes, plot the sailing directions» which were widely used, in particular, in the Coffin Texts. Units of «prospectors»-srjw were generally a part of the expeditionary force in the quarries of the Sinai, Wadi Hammamat, Hatnub, Nubia and other remote locations. Nevertheless, according to the titles of their superiors, srjw could serve in the Nile valley as well. Functions of such srjw in Egypt itself, probably, were to accompany goods and to send reports along the routes that were plotted by them, while outside of the Nile valley they were conducting the prospecting. The ordinary srjw and smntjw, along with different categories of soldiers and craftsmen, had a very modest status, so there are almost no inscriptions of them107.

107. Data about the single title smntj of Middle Kingdom, presented in Rainer Hannig’s dictionary, are either incorrect (for example, on stela Cairo CG 20457 it is the personal name mnjw, cf. Fischer 1996a, 177) or doubtful (for example, on stela «cCassirer» (Schlögl 1978, 49, 155; cf. Meeks 1998, II, 327, 78.3547) a title of musician is mentioned, most probably, it means «castanets or sistrum player» (srwj?/sxmj?) rather than smntj), or represent the group spelling (Hannig 2006, 2212 {28076}). About the ordinary title srj: Tallet 2012a, I, 218–219, II, 154 (CCIS 247).

1. The title jmj-xt srjw «under-supervisor of prospectors».

I chose for the rank jmj-xt (literally meaning «one who follows, one who goes after») the conditional translation «under-supervisor»108. This rank was the second in the phyle of employees directly after «inspector» sHD. In the Middle Kingdom the hierarchic rank jmj-xt disappeared from almost all government bodies, apart from the police: it remained only as part of the title jmj-xt zAw-prw «under-supervisor of policemen (or gendarmes, literally «sons of the house(s)»)»109.

109. Jones 2000, 296 (1081): «under-supervisor of sons-of-houses (police)»; Hannig 2003, 132; 2006, 240–241.

The title jmj-xt srjw «under-supervisor of prospectors» held by the author of the inscription, nj-kA=j-ra, is unique. The only parallel to it from the sphere of organization of the expeditions, is the office of jmj-xt smntjw «under-supervisor of guides» which occurs very rarely as well:

1. In graffito of Htpw in the form jmj-xt smntjw mrr nb=f «under-supervisor of guides beloved of his lord»110.

2. On a sealing with the name of king [Hr] wsr-xaw from Buhen111.

3. On a sealing with the name of king Hr Dd-xaw, Dd-kA-ra from Edfu in the form [jmj]-xt smntjw jrr wDt nb=f «under-supervisor of guides who does what his lord commands»112.

The unique title in Wadi Hammamat, published in transcription as jmj-xt mSa «under-supervisor of army»113, should most likely be read as jmj-xt smntjw «under-supervisor of guides”.

The only known namesake of nj-kA=j-ra served in the administration of the contingent of srjw is wr mDw Smaw zS «great (among) the tens of Upper Egypt, scribe»114 nj-kA=j-ra. He left behind many monuments115, and his titulary is exclusively rich with offices from different spheres of activity116. He was a priest Hm-nTr of kings [sAH]w-[ra], Hr [wsr-xa]w (nfr-jrj-kA-ra), Hr st-jb-tAwj (nj-wsr-ra) and Hm-nTr ra «priest of the Sun» in the Sun temples [st]-jb-[ra] (of king nfr-jrj-kA-ra) and Szp(w)-jb-ra (of king nj-wsr-ra). The main activity nj-kA=j-ra related to the ministry of food where he held several offices117: [jmj-rA] Snwtj «overseer of the (department of) two granaries», [jmj-rA] zSw mDAt n(j) Snwt «overseer of scribes of documents for the (department of) granary», jmj-rA Snwt n(j)t Xnw «overseer of the (department of) granary for residence», Xrj-tp Snwt «overseer of the (department of) granary», sHD zSw Snwt «inspector of scribes of the (department of) granary»118. The title jmj-rA Snwt «overseer of the (department of) granary» was also held by his son anx-m-a-ra. nj-kA=j-ra himself was also involved into organization of cattle breeding and hunting which is evidenced by such his titles as jmj-rA Hwt-aAt «overseer of the great estate», jmj-rA Hwt-jHwt «overseer of the estate for the cattle breeding (with the town determinative)», jmj-rA Apdw-S «overseer of pond-fowl»119, jmj-rA pHww nb «overseer of all marshlands», jmj-rA nww nb «overseer of all hunters», jmj-rA bjtjw nb «overseer of all bee-keepers»120. Such unusual offices as jmj-rA (Xrjw)-sbA nb «overseer of all parasol bearers»121 and jmj-rA msw nswt (prw) m prwj «overseer of the (houses of) king's children in the two houses» can also be added into this group.

115. PM III.2 1981, 696–697. The monuments of nj-kA=j-ra include: 1-2. Statue Cleveland Museum of Art 1964.90 and fragments of false door Cleveland Museum of Art 1964.91 (Andreu 1997, 21–30; Fischer 1997, 178–179; Hamza Awad 2006, 73–87; Berman, Bohač 1999, 128–132 (71–72); >>>> ; >>>> ); 3. Statue Brooklyn 49.215 (James 1974, 13 (36), pl. 19; >>>> ); 4–5. Statues New York, MMA 52.19 and 48.67 (www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/543900; >>>> ). Probably from Saqqara. Dating: nj-wsr-ra.

116. About titles of nj-kA=j-ra see also Baud 1999, II, 481, no. 103 (V 6); Nuzzolo 2018, 360–361 [51]; Florès 2015, 417 (Ni/Sa/1).

117. The Old Kingdom «overseers of the granary / two granaries» performed the functions of the agriculture ministers. This office was reliably attested from the beginning of the 5th Dynasty (Strudwick 1985, 251–275).

118. The title Xrj-tp Snwt «chief of the (department of) granary» is mentioned on statues Cleveland Museum of Art 1964.90, New York, MMA 52.19 and 48.67; the titles rx nswt «king's acquaintance» and sHD zSw Snwt «inspector of scribes of the (department of) granary» is attested only on statue Brooklyn 49.215.

119. For the reading Apdw-mr/S «channel-bird, pond-fowl» see Hayes 1951a, 53, fig. 13 (170–181); 1951b, 92–93; Wassell 1991, II, 27–28, n. 98; Bailleul-LeSuer 2016, 29, 341, 377–378, 381. Cf. Andreu 1997, 22; Fischer 1997, 178; Jones 2000, 52 (258); Diego Espinel 2006, 87; Hamza Awad 2006, 75, 80; Nuzzolo 2018, 360: everyone is reading the title as sS(.w)?, or as Apd(w), or as Apd(w)-mr/S. Reading in Florès 2015, 417: «(j)m(y)-r(A) sA mr ?».

120. Reading in Hamza Awad 2006, 75, 78: «jmj-rA [...] bjt nb(.w)?» is incorrect.

121. Cf. readings in Hamza Awad 2006, 75, 78: «jmj-rA sb[...] nb(.w)?»; Nuzzolo 2018, 360: «imy-r sb(w) […] nb(w)»; Florès 2015, 417: «(j)m(y)-r(A) sb [... ?] nb». About this title: Bogdanov, Bolshakov 2004, 23; this article was afterwards reprinted in English: Bolshakov 2005, 47, n. j).

The title jmj-rA srjw  on false door Cleveland 1964.91 looks unusual122

on false door Cleveland 1964.91 looks unusual122 ; writing of the word srj by only the ideogram of the official without any phonetic complement is reliably attested only in inscription Sinai 19 written by sHD srjw «inspector of prospectors» snnw jdw123

; writing of the word srj by only the ideogram of the official without any phonetic complement is reliably attested only in inscription Sinai 19 written by sHD srjw «inspector of prospectors» snnw jdw123..png) . Nevertheless, the title jmj-rA srjw on false door Cleveland 1964.91 apparently has nothing to do with the organization of expeditions. The titulary of nj-kA=j-ra is in many respects similar to the titulary of dmD124

. Nevertheless, the title jmj-rA srjw on false door Cleveland 1964.91 apparently has nothing to do with the organization of expeditions. The titulary of nj-kA=j-ra is in many respects similar to the titulary of dmD124, as well as the bases of statues Cairo CG 305 and CG 313 (Borchardt 1911, 182, 184). Dating: nj-wsr-ra – mn-kAw-Hr..png) who also held the office of

who also held the office of  jmj-rA srjw and also was jmj-rA zS «overseer of the fowling pool» (the sense of the title is not known), jmj-rA Snjw-tA nb «overseer of all vegetation», jmj-rA pHww «overseer of marshlands», jmj-rA wHaw «overseer of fowlers/fishermen» and a priest of the Sun (Hm-nTr ra) in the Sun temples sxt(-ra) (of king sAHw-ra) and st-jb-(ra) (of king nfr-jrj-kA-ra)125

jmj-rA srjw and also was jmj-rA zS «overseer of the fowling pool» (the sense of the title is not known), jmj-rA Snjw-tA nb «overseer of all vegetation», jmj-rA pHww «overseer of marshlands», jmj-rA wHaw «overseer of fowlers/fishermen» and a priest of the Sun (Hm-nTr ra) in the Sun temples sxt(-ra) (of king sAHw-ra) and st-jb-(ra) (of king nfr-jrj-kA-ra)125 .

.

According to these indirect data, the office of jmj-rA srjw held by dmD and nj-kA=j-ra was probably related to the management of auditors126 or guides127. Needless to say, that the bosses themselves did not participated in the trips - their status did not allow them. Here, as in the expedition inscriptions, the title srjw - in broad sense «informer, prospector, auditor, researcher» - has one meaning but different content. In Egypt srjw could play a role of attendants of the military or fiscal missions, and in expeditions the many professional miners and prospectors were called by the same title.

127. Urk I, 65.17 = Brovarski 2000, 108–109, pl. 75–78a, fig. 23; text fig. 4; Diego Espinel 2011, 60, fig. 8 (no. 120); Edel 2008, I, 50–51, 243 (Abb. 32), Text 59, Taf. 9 = Seyfried 2005, 314–318 (tomb QH 26) et al.

Thus, competence of two persons named nj-kA=j-ra with the resembling titles turns out to be ghost and their identity - unreliable.

2. The title sHD srjw «inspector of prospectors»128.

Bearers of the title sHD srjw can be divided into two categories: 1. The expedition members as inspectors of prospectors. 2. Officials of the fiscal service, «inspectors of auditors». The first ones left their inscriptions outside of Egypt, the others, with few exceptions, are known from the monuments from their own tombs in the Memphite region, at Giza and Saqqara. Since it is not easy to identify the functions of officials from the second group, I present their prosopography separately.

1. The expeditionary sHDw srjw «inspectors of prospectors» left inscriptions in the Sinai, in Wadi Hammamat and Hatnub.

1.1. A collective: sHD srjw 20 «inspector of 20 prospectors». Inscription Hatnub Gr. 3.12129 smsw «elder» instead of sHD srjw (Anthes 1928, 20; Eichler 1993, 43 (39) et al.). This reading appeared because of a mistake in the transcription (cf. Anthes 1928, 20, Anm. 12: he believes that it is the drawing that is incorrect, and not the transcription). Although in the facsimile of the hieratic inscription made by G. Möller it is the sign HD which is obvious and not m, everybody is oriented to the hieroglyphic transcription which results in a mistake. Based on this uncertain reading, M. A. Lebedev devoted half a page of the text to description of activities of the expedition members with the title sms.w which he interpreted as «foremen of (carpenter shops)» (Lebedev 2015, 84, 419) although they were not mentioned in the expedition inscriptions at all.]]] from «year of the 14th occasion (of the counting)» i. e. 27/28th regnal year of king Hr nTrj-xaw (ppj II nfr-kA-ra). The numeral 20 after the title, with the determinative A1 pl. instead of the name, look strange, although it is understandable in the standard name list of the crew.

smsw «elder» instead of sHD srjw (Anthes 1928, 20; Eichler 1993, 43 (39) et al.). This reading appeared because of a mistake in the transcription (cf. Anthes 1928, 20, Anm. 12: he believes that it is the drawing that is incorrect, and not the transcription). Although in the facsimile of the hieratic inscription made by G. Möller it is the sign HD which is obvious and not m, everybody is oriented to the hieroglyphic transcription which results in a mistake. Based on this uncertain reading, M. A. Lebedev devoted half a page of the text to description of activities of the expedition members with the title sms.w which he interpreted as «foremen of (carpenter shops)» (Lebedev 2015, 84, 419) although they were not mentioned in the expedition inscriptions at all.]]] from «year of the 14th occasion (of the counting)» i. e. 27/28th regnal year of king Hr nTrj-xaw (ppj II nfr-kA-ra). The numeral 20 after the title, with the determinative A1 pl. instead of the name, look strange, although it is understandable in the standard name list of the crew.

1.2. jHj-n=s (son of?) Hnkw(?): sHD srjw [smntjw] «inspector of prospectors and [guides]». Inscription Wadi Hammamat M 151130. E. Eichler131 identified the author of the inscription jHj-n=s132 with anx-mrj-ra/ jHj-n=s of stela Cairo CG 1483133, however his equating is absolutely arbitrary. anx-mrj-ra/ jHj-n=s was an important nobleman, «overseer of the (department) of all the works of the king» (jmj-rA kAt nbt nt nswt), but jHj-n=s from Wadi Hammamat was only the commander of an expedition crew.

131. Eichler 1993, 75.

132. To the reading of the name jHj-n=s: Fischer 1996a, 60–61; cf. Scheele-Schweitzer 2014, 260 [451]: JH.y-n=s (?)/N(.j)-sw-JH.y (?) «ein JH.y für sie! (?)/ er gehört dem Ihi (?)».

133. PM III.2 1981, 586; Borchardt 1937, 174–175, Bl. 39. Dating: mrj.n-ra – ppj II.

1.3. jd[w?]: [sHD?] srjw «[inspector?] of prospectors». Hieratic ink inscription on gypsum Ayn Soukhna CCIS 250134.

1.4. wAS-k(A=j), Htp-n=j-j, nj-sbk: three persons with a collective title sHD srjw «inspector of prospectors». Inscription Sinai 13135. All the three as holders of this office are not attested in other sources.

1.5. Htp:  sHD srjw «inspector of prospectors». Inscription Ayn Soukhna CCIS 214136

sHD srjw «inspector of prospectors». Inscription Ayn Soukhna CCIS 214136 . Judging from the photograph, the usual determinative A1 follows the sign sr, and the small sign xAst is absent at all.]]].

. Judging from the photograph, the usual determinative A1 follows the sign sr, and the small sign xAst is absent at all.]]].

1.6. sAbj-km: mSa sHD srjw «expeditionary inspector of prospectors». Inscription Sinai 20137 . The ideogram of the soldier with the meaning mSa «army, expedition, campaign» stands in front of the title. The title is written in accordance with the habitual standard for the titles with the element pr-aA, which as a stand-alone title simply means «palace attendant» and in most other cases is put in front of the title as the place of service, for example, as in the title rx nswt pr-aA «king's acquaintance of the palace». Nevertheless, it should be recognized that the ideogram mSa herein means «campaign, march» rather than «army». Similar method was used in the title of jdw: jmj-rA srjw mSa «expeditionary overseer of prospectors»138

. The ideogram of the soldier with the meaning mSa «army, expedition, campaign» stands in front of the title. The title is written in accordance with the habitual standard for the titles with the element pr-aA, which as a stand-alone title simply means «palace attendant» and in most other cases is put in front of the title as the place of service, for example, as in the title rx nswt pr-aA «king's acquaintance of the palace». Nevertheless, it should be recognized that the ideogram mSa herein means «campaign, march» rather than «army». Similar method was used in the title of jdw: jmj-rA srjw mSa «expeditionary overseer of prospectors»138. Gardiner, Peet, Černý 1952, pl. 10; Černý 1955, 65; Edel 1983, 165–169, Abb. 3a–b; Tallet 2012a, I, 30, II, 10; 2018, 305. Wadi Maghara. Dating: jzzj(?)..png) , which is also attested with the sign mSa «army» in the postposition and determinative A1 in the title of Htp:

, which is also attested with the sign mSa «army» in the postposition and determinative A1 in the title of Htp:  jmj-(rA) srjw mSa139

jmj-(rA) srjw mSa139. Wadi Maghara. Dating: 2nd half of 5th - 6th Dynasties..png) .

.

1.7. snnw jdw: sHD srjw «inspector of prospectors». Inscription Sinai 19 (CCIS 8)140. With high probability he is identical with [sHD?] srjw jd[w?] (1.3)141.

141. Tallet 2018, 108–109.

1.8. kAj: sHD srjw smntjw «inspector of prospectors and guides». Inscriptions Wadi Hammamat M 163, M 166, M 167142. The title spellings are following143: (M 163); (M 167, M 166). kAj also held offices of xrp aprw nfrw «captain of a squad of recruits» and jmj-rA 10 wjA «overseer of ten of a boat (i.e. 10 boatmen)» (Wadi Hammamat M 165).

143. There are no photographs of the inscriptions in Couyat & Montet’s publication. I used photographs available on the website ancienegypte.fr/ouadi_hammamat/page2.htm (33.jpg, 41.jpg).

2. Interpretation of the title sHD srj(w) in tomb inscriptions depends solely on the context, namely on the accompanying titles clarifying the sphere of activity and other indirect criteria. In most cases the title srjw should be understood as «auditors, fiscal agents, informers», although it could also be the expedition members as shown in the case of the offering basin from tomb G 1111. Prosopography of bearers of the title sHD srj(w) on the monuments from the Memphite region include the following persons:

2.1. anx-kAkAj:  sHD srj(w) jrj-jxt jz nwd(w) Xkr(w) nswt «inspector of auditors, custodian of property of the division of unguents of the (department of) king’s regalia»144

sHD srj(w) jrj-jxt jz nwd(w) Xkr(w) nswt «inspector of auditors, custodian of property of the division of unguents of the (department of) king’s regalia»144. Dating: first half of the 5th Dynasty..png) . That functionary was an official of the department of king’s regalia (Xkr(w) nswt) which was divided into two offices (jzwj)145

. That functionary was an official of the department of king’s regalia (Xkr(w) nswt) which was divided into two offices (jzwj)145 . One of them included a division of nwd(w) unguents146

. One of them included a division of nwd(w) unguents146 , where anx-kAkAj worked as a petty clerk, performing, in particular, the functions of an «inspector of auditors», which is not surprising given the value of products manufactured at the department establishments.

, where anx-kAkAj worked as a petty clerk, performing, in particular, the functions of an «inspector of auditors», which is not surprising given the value of products manufactured at the department establishments.

2.2. nj-anx=j-bAstt: sHD srj(w). He was a funerary priest (“ka-servant”, Hm-kA) of the tomb owner, DfAw, who held the office of jmj-rA prwj-HDwj «overseer of the double silver-house»147. That nobleman, who was the head of the entire finance department, appointed his proper servant nj-anx=j-bAstt a clerk at government service; his status was the same as that of anx-kAkAj (2.1).

2.3. nfr-jHj:  sHD srj(w)148

sHD srj(w)148. Dating: first half of the 5th Dynasty..png) . He was also holding the title rx nswt «king's acquaintance» which was the lowest indicator of nobility. Occupation of nfr-jHj remains uncertain.

. He was also holding the title rx nswt «king's acquaintance» which was the lowest indicator of nobility. Occupation of nfr-jHj remains uncertain.

2.4. nTr-nfr:  sHD srj(w)149

sHD srj(w)149. Giza. Dating: late 4th Dynasty..png) . Occupation is uncertain.

. Occupation is uncertain.

2.5. xww-ra:  sHD srjw. He held a unique priestly title

sHD srjw. He held a unique priestly title  Hm-ntr Xnmw mrj Hr «priest of Khnum beloved by Horus»150

Hm-ntr Xnmw mrj Hr «priest of Khnum beloved by Horus»150. Dating: wnjs..png) . Occupation is uncertain.

. Occupation is uncertain.

2.6. kA=j-apr151. Dating: second half of the 5th Dynasty..png) : jmj-rA srjw,

: jmj-rA srjw,  sHD n(j) srjw. Other titles: rx nswt «king's acquaintance», sqd n wjA «rower of a boat»152

sHD n(j) srjw. Other titles: rx nswt «king's acquaintance», sqd n wjA «rower of a boat»152; Hannig 2003, 1248..png) , [...] sr n S[...]? wjA «[...] boat», nst-xnt(j)t «upper throne», wDa-mdw m Hwt-[wrt] «judge in the Hall of Justice»153

, [...] sr n S[...]? wjA «[...] boat», nst-xnt(j)t «upper throne», wDa-mdw m Hwt-[wrt] «judge in the Hall of Justice»153..png) , wD-mdw n(j) Hrj(w)-wDbw «giver of orders of the (department of) distribution»154

, wD-mdw n(j) Hrj(w)-wDbw «giver of orders of the (department of) distribution»154..png) , jmj-rA mSa «general», jmj-rA Snwt «overseer of kraal»155

, jmj-rA mSa «general», jmj-rA Snwt «overseer of kraal»155, the title means «the overseer of the granary», which is incorrect. The title is to be read jmj-rA Snw «overseer of kraal» (Jones 2000, 252–253 (914–915); to add the title of DfA-nswt (architrave from tomb G 1171: www.gizapyramids.org: C12000_OS) who also held the title xrp apr sqd(w) jz(t) wjA «captain of a squad of the boat crew». For the meaning of term Snwt/Snw in the title jmj-rA Snw as «kraal, circular camp» of Nubian tribes see Abu Bakr, Osing 1973, 101, 106, 109, 110; Osing 1976a, 135, 137, 155; see also Bogdanov 2014, 7, 14, note 9). There is no reason to confuse «police» SnT (SnT > Snt) with «squad» Snw(t). Usage of this term in Egyptian military titles indicates that Nubian soldiers serving in Egyptian army were recruited in units based on their tribal affiliation..png) . This person combined naval, military and judicial titles in his titulary. According to the naval titles kA=j-apr, I tend to interpret the group srjw on his relief as the expedition members, prospectors.

. This person combined naval, military and judicial titles in his titulary. According to the naval titles kA=j-apr, I tend to interpret the group srjw on his relief as the expedition members, prospectors.

3. Dubia:

3.1. jnj, who held the title  smsw wxr(j)t, sHD [...] «elder of the dockyard156

smsw wxr(j)t, sHD [...] «elder of the dockyard156; Hannig 2003, 1144..png) , inspector [...]»157

, inspector [...]»157..png) . The reading sHD sr(w) q[nb]t «inspector of the law [court] sr(w)-officials (?)» indicated by the publisher is incorrect.

. The reading sHD sr(w) q[nb]t «inspector of the law [court] sr(w)-officials (?)» indicated by the publisher is incorrect.

3.2. bbj held the title  sHD nfr(w) srjw(?) «overseer of recruits and prospectors (?)»158

sHD nfr(w) srjw(?) «overseer of recruits and prospectors (?)»158 awt nb(t) «year after the 12th occasion of the counting of all the small cattle» (24/25th years of Cheops’ reign)..png) . Possibly the sign sr happened to be here by chance instead of the determinative

. Possibly the sign sr happened to be here by chance instead of the determinative  «child» for the word nfrw «recruits». In another graffito of bbj his title is already given in a more standard form: sHD(w) nfrw stp-zA «overseer(s) of recruits of security» jj-mrj and bbj159

«child» for the word nfrw «recruits». In another graffito of bbj his title is already given in a more standard form: sHD(w) nfrw stp-zA «overseer(s) of recruits of security» jj-mrj and bbj159 .

.

TO THE IDENTIFICATION OF sHD srjw «OVERSEER OF PROSPECTORS» jww-nmtj

It is possible to single out two persons with the name jww-nmtj, serving in the administration of srjw, among the authors of the inscriptions. I present their data according to prosopography of the bearers of the name jww-nmtj given above:

2.3. jww-nmtj. Title: jmj-rA sr(jw) «overseer of prospectors». Inscription Sinai 13 from rnpt m-xt zp 4 Tnwt jHw awt nb «year after the 4th occasion of the counting of all the large and small cattle», i. e. 8/9th regnal year of king Dd-kA-ra jzzj.

2.8. jww-nmtj. Title: jmj-rA 10 srjw smntjw «overseer of ten prospectors and guides». Graffito in Gebel Abrak (Eastern desert).

Discrepancies in the ranks jmj-rA/sHD «overseer/inspector» are non-essential in this case. Two cases of combination of these ranks in the sphere of srjw corporation can be distinguished: 1. In the titulary of kA=j-apr who mentions the titles jmj-rA srjw and sHD n(j) srjw in his own tomb. 2. According to P. Tallet160, jdw (or snnw jdw) mentioned in inscriptions Sinai 19 (CCIS 8), Sinai 21 (CCIS 9), Sinai 22 (CCIS 7)161 and CCIS 250 is one and the same person, a member of the expedition to the Sinai under the reign of king Dd-kA-ra jzzj. Therefore, he held the offices of sHD srjw (mentioned in CCIS 8 and CCIS 250) and jmj-rA srjw (mentioned in CCIS 9) at the same time.

161. Tallet 2012a, I, 28, II, 9; 2018, 305. Wadi Maghara.

There is nothing worth saying about jww-nmtj of the Abrak inscription; besides, it is difficult to date it exactly. As for jww-nmtj (2.3) of inscription Sinai 13, nothing prevents this identification. Almost certainly, this official is identical with the owner of the offering basin from tomb G 1111, this is why the tomb should also be dated to the reign of Dd-kA-ra jzzj.

Since long, inscription Sinai 13 has attracted great attention from many researchers owing to its unusual content162. The list of members of the expedition to the turquoise mines presented therein includes the preamble which is often considered as the first evidence on the divine oracle in Egypt. According to this text, the expedition to the Sinai was inspired by finding the god's assignment on the precious stone in the broad court of the temple nxn-ra «Stronghold of the Sun», the Sun temple of king wsr-kA=f. The offering basin from tomb G 1111 may prove to be the first monument belonging to a member of that expedition - overseer and inspector of prospectors-sr(jw) jww-nmtj.

List of abbreviations

PM III.1 1974 – Porter, B., Moss, R.B. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. Vol. III. Memphis. 2nd ed. Pt. 1. Abû Rawâsh to Abûṣîr. Oxford.

PM III.2 1981 – Porter, B., Moss, R.B. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. Vol. III. Memphis. 2nd ed. Pt. 2. Ṣaqqâra to Dahshûr. Oxford.

PM V 1937 – Porter B., Moss R.B. Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Reliefs and Paintings. Vol. V. Upper Egypt: Sites. Oxford.

PM VIII.1 1999 – Malek, J., Magee, D. Miles, E. (eds.), Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings. Volume VIII: Objects of Provenance Not Known. Part I: Royal Statues, Private Statues (Predynastic to Dynasty XVII), Oxford.

PM VIII.3 2007 – Malek, J., Fleming, E., Hobby, A., Magee, D. (eds.), Topographical Bibliography of Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphic Texts, Statues, Reliefs and Paintings. Volume VIII: Objects of Provenance Not Known. Part 3: Stelae (Early Dynastic Period to Dynasty XVII). Oxford.

Urk. I 1932-1933 – Sethe, K. (ed.), Urkunden des Alten Reiches. 2. Aufl. (Urkunden des ägyptischen Altertums, Erste Abteilung, 1). Leipzig, 1932-1933.

Wb. – Erman, A., Grapow, H. (Hrsg.), Wörterbuch der ägyptischen Sprache. Bd. I–V. 4. Aufl. Berlin, 1982.

Библиография

- 1. Abdel-Raziq, A. 2017: An unpublished lintel of Ahmose-Nebpehtyre from El-Atâwla. Journal of the American Research Center in Egypt 53, 47–55.

- 2. Abu Bakr, A.M., Osing, J. 1973: Ächtungstexte aus dem Alten Reich. Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts. Abteilung Kairo 29, 97–133.

- 3. Adams, M.D. 2010: The stela of Nakht, son of Nemty: contextualizing object and individual in the funerary landscape at Abydos. In: Z. Hawass, J. Houser Wegner (eds.), Millions of jubilees: studies in honor of David P. Silverman. Vol. I. (Supplément aux Annales du Service des Antiquités de l'Egypte, 39). Le Caire, 1–25.

- 4. Andreu, G. 1997: La fausse-porte de Nykarê, Cleveland Museum of Art 64.91. In: C. Berger, B. Mathieu (éd.), Études sur l’Ancien Empire et la nécropole de Saqqâra dédiées à Jean-Philippe Lauer. T. I. (Orientalia Monspeliensia, 9). Montpellier, 21–30.

- 5. Anthes, R. 1928: Die Felseninschriften von Hatnub: nach den Aufnahmen Georg Möllers. (Untersuchungen zur Geschichte und Altertumskunde Aegyptens, 9). Leipzig.

- 6. Assmann, J. 1999: Ägyptische Hymnen und Gebete: übersetzt, kommentiert und eingeleitet. 2. Aufl. Freiburg (Schweiz)–Göttingen.

- 7. Bailleul-LeSuer, R.F. 2016: The Exploitation of Live Avian Resources in Pharaonic Egypt: a Socio-Economic Study. PhD Diss. University of Chicago. URL: oi.uchicago.edu/sites/oi.uchicago.edu/files/uploads/shared/docs/Research_Archives/Dissertations/Rozenn%20Dissertation%20052516.pdf; дата обращения: 14.04.2021.

- 8. Baines, J., Parkinson, R.B. 1997: An Old Kingdom record of an oracle? Sinai inscription 13. In: J. van Dijk (ed.), Essays on Ancient Egypt in Honour of Herman te Velde. (Egyptological Memoirs, 1). Groningen, 9–27.