- Код статьи

- S032103910015609-2-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S032103910015609-2

- Тип публикации

- Статья

- Статус публикации

- Опубликовано

- Авторы

- Том/ Выпуск

- Том 81 / Выпуск 2

- Страницы

- 720-744

- Аннотация

The authors present a new publication of Tamin’s coffin from the collection of the Research Institute and Museum of Anthropology, Lomonosov Moscow State University. The article provides a detailed discussion of the coffin’s provenance. Based on the translation and analysis of the inscriptions on Tamin’s coffin and on the comparison of these inscriptions with similar texts on other coffins, the authors suggest an origin from Akhmim for it. The distinctive stylistic and paleographic features of the inscription, the language and errors encountered in the text, the titles and epithets further allow us to date the coffin to the Ptolemaic period. Comparison of Tamin’s coffin with other similar objects, namely, with Tasheretmin’s and Hentykhetyemhotep’s coffins, as well as with a whole group of other stone sacrophagi, allows us to determine the possible date of the Moscow object more precisely: the end of the third – first half of the second centuries BC.

- Ключевые слова

- Ptolemaic period, Akhmim, coffins, offering list, Tamin

- Дата публикации

- 28.06.2021

- Год выхода

- 2021

- Всего подписок

- 11

- Всего просмотров

- 204

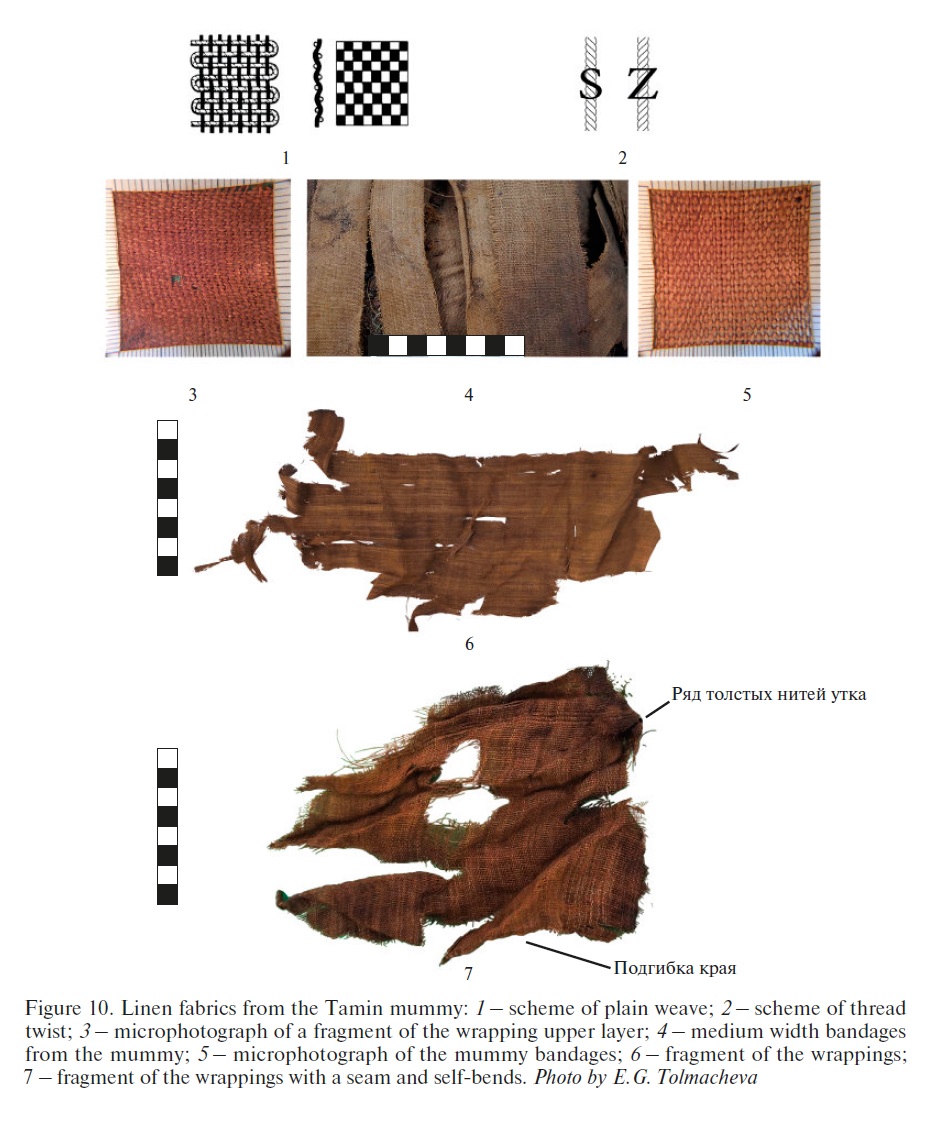

This article continues the series of publications of the artifacts1 which are included in the collection of Research Institute and Museum of Anthropology, Lomonosov Moscow State University. At present it consists of three ancient Egyptian mummies, one of which lies in a coffin, and of linen burial fabrics. The subject of this publication is the mummy in the coffin.

ARTIFACT PROVENANCE

This coffin, according to the inscription on it, belonged to Lady Tamin (KP (book of accessions) 5 №3482/1,2; KO (brief description) 366), it made a very long, not fully traced, way through the museum collections of Russia before ending up in Museum of Anthropology of Lomonosov Moscow State University.

Archive sources make it possible to reconstruct the history of Tamin's coffin museum storage with confidence from only 1921. In that year, The Moscow public and Rumyantsev museum was defunct, and its collections were distributed among the other Moscow collections. 859 ancient Egyptian artifacts from the antiquarian section were transferred to Museum-Institute of the classical East (MICE)2. "Four mummies in coffins and paperboard containers" were among the Egyptian artifacts.

MICE "was organized at the end of 1917 on the premises of Russian historical museum and began its activities in January, 1918 which was in line with a pronounced request for establishing a specialized scientific and popularization institute in Moscow dedicated to issues of ancient oriental studies"3. MICE existed until 1924.

4 coffins with mummies, 1 coffin without mummy, 1 mummy with a cartonnage casing, 1 mummy dated to Greco-Roman times and one unwrapped mummy were listed in the shorter inventory of artifacts stored in MICE in 19244. 4 coffins with mummies are registered in MICE collection inventory for the same 19245. The following was described under No 5 - "Anthropoid coffin, painted red, mask – yellow with blacken eyes and eyebrows. Below the knees and on the feet (six vertical lines) and images of two jackals lying on the pylons. All that was covered with black paint. The coffin is complete with a glass cover and wooden stand. The coffin encloses Woman's mummy, No. 6"6.

5. Department of manuscripts, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. 1924. F. (Fund) 4. Op. (List of files) 1. Ed. (Shelving unit) 73. L. (Sheet) 3.

6. Department of manuscripts, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. 1924. F. (Fund) 4. Op. (List of files) 1. Ed. (Shelving unit) 73. L. (Sheet) 8.

It follows from the description of the mummy (No. 5) that it undoubtedly is that very artifact currently stored in Research Institute and Museum of Anthropology. It is curious that the mummy was defined as a woman's one. In the current preservation state of the mummy, it would have become possible to determine that only after X-ray study. Apparently, the inventory compiler managed to read the deceased name or, based on the mask color, made an assumption that a woman's mummy was lying in the coffin. But it can be assumed that Tamin's mummy was X-ray studied which made it possible to unmistakably identify its gender. It is known that MICE started "X-ray analysis of mummies" already in 1921. As stated in the activity report of the Museum-Institute, "this analysis shall help to resolve several issues without any damage to the artifacts, and namely: presence of inclusions of all sorts – chest scarabs, amulets, decoration and, may be, papyri, etc., in some cases – diseases which affected the mummified persons, etc."7. It is not excluded that Tamin's mummy was X-ray studied. MICE report for 1921 says that X-ray analysis of the following objects was performed:

- Human arm and leg.

- 3 mummies of the sacred hawks.

- Small crocodile mummy.

- Woman's mummy dated to Ptolemaic times.

The X-ray studies helped to diagnose: 1) age, 2) breed and gender, 3) complete anatomical organization, 4) severe tuberculosis of the leg bones with the knee-cap dislocation. Autopsy of the mummy dated to Ptolemaic times was also performed since earlier the mummy was stored in the unheated premises of Stroganov School for Teaching Drawing; and the rotting process started. The mummy was found if a relatively good condition. The detailed autopsy protocol complete with sketches is being stored in the Museum-Institute premises8.

Given that the very four mummies in coffins and adored with cartonnages car were transferred from Rumyantsev museum to MICE, it is logical to assume that the coffin with mummy, stored in Research Institute and Museum of Anthropology at present, came exactly from Rumyantsev museum.

However, already in the same 1924, this coffin and mummy, among other wooden coffins with mummies (1,1а 1234, 1235, 1290), were transferred from MICE to the Fine Arts Museum (today's Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts)9.

Tamin's coffin with the mummy was stored in the Museum at Volkhonka, 12 through to 1932 when head of the oriental department, V. I. Avdiev exchanged it for Ius-Ankh's coffin from the collection of the Central anti-religious museum (CAM). After dissolution of CAM in 1948 Tamin's coffin with the mummy inside was transferred to Museum of Anthropology of MSU10.

PUBLICATIONS

For the first time ever, Tamin's inner coffin was published by O. D. Berlev and S. I. Hodjash in 1998 in Catalogue of the Monuments of Ancient Egypt from the Museums of the Russian Federation, Ukraine, Bielorussia, Caucasus, Middle Asia and the Baltic States which was issued in English in Goettingen11. The publication included two photographs of the artifact, theEnglish translation of the inscriptions on the coffin and comments to the translation. Unfortunately, it appears that the authors of that catalogue were unable to get acquainted with the artifact directly: the text does not describe the coffin, its dimensions, inventory number, information from the accession book, and from all appearances, the translation of the inscriptions was made according to an unpublished trace drawing and photographs12. Thus, no complete publication of the coffin and the mummy was not presented so far which makes it relevant to have a scholarly publication on the artifact complete with newest photographs, trace drawings of the inscription, hieroglyphic text, transliteration, redefined translation and comments.

12. Berlev, Hodjash 1998, 34, n. 1.

In their comments to the inscriptions O. D. Berlev and S. I. Hodjash paid quite a lot of attention to the artifact historical context. In the view of the first publishers, the coffin is undoubtedly of Akhmin provenance, and some features of the text of the standard offering formula hetep-di-nesu, made on it, indicate that the coffin owner, Tamin, belonged to the rebellious royal dynasty (researchers thought that she was a half niece of Horwennefer and Ankhwennefer rulers) who led a rebellion of the Egyptians against Ptolemaic domination in 205-186 B. C. Moreover, O. D. Berlev and S. I. Hodjash thought that the coffin from the collection of Museum of Anthropology carried the first reference to representatives of that, so called anti-Ptolemaic, dynasty13. The coffin was not published anymore, however the monograph Spätägyptische Särge aus Achmim: eine typologische und chronologische Studie". by German researcher R. Brech was published in 2008 where the author also presented some information about Tamin's coffin based on O. D. Berlev and S. I. Hodjash publication14. Based on studying typology of Late Egyptian and Ptolemaic coffins and the very inscription on Tamin's coffin15 R. Brech agreed to Moscow coffin dating proposed by the first publishers but saw no indication in this text of relation between the object and so called anti-Ptolemaic dynasty.

14. Brech 2008, 161–163, 332–334.

15. R. Brech was unable to get acquainted with the inscription directly, all of her conclusions were made on the basis of studying the publication by Berlev and Hodjash and researching the coffin black-and-white photographs presented in this only publication.

ARTIFACT DESCRIPTION

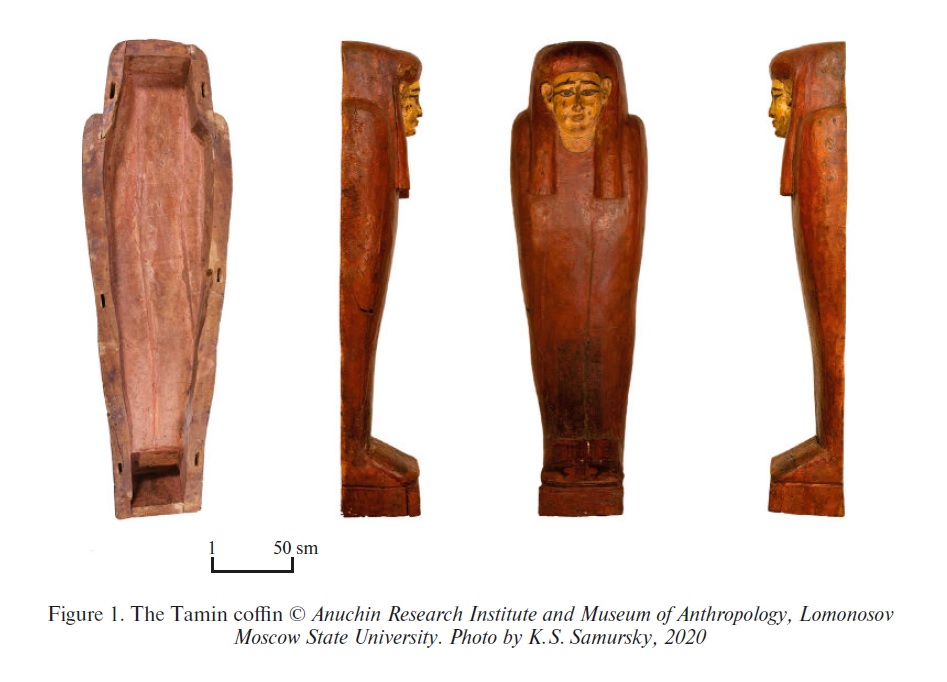

The anthropoid coffin was made of sycamore wood16. It consists of two parts – lid with the mask and lower part (bottom) which are connected with each other in six places with the use of the standard tong-and-groove jointing (Figure 1; 2,1). The coffin length – 191 cm, width at shoulders – 48 cm, height – 35 cm. The lid is a sculptural image of the wrapped figure of the deceased. The arms are not delineated. The coffin ends with the rectangular base stand – pedestal on which the figure itself stands.

The coffin lid is complex, its front part is made of three close-fitted wood boards, clearances between the boards are filled with sealing coat. Side faces of the coffin lid are made of six separate boards: three small ones of rectangular shape in the area of the head, two long boards of the coffin sides and almost square end-face board at the coffin foot. All seams between the boards are carefully sealed with gesso. The wood surface was subjected to additional treatment, primed and coated with red-brown paint. Study of the pigment composition and binding agent was not done. It is not known if any paint protecting coating was used in ancient times: it either did not survived or was partially removed during contemporary conservation.

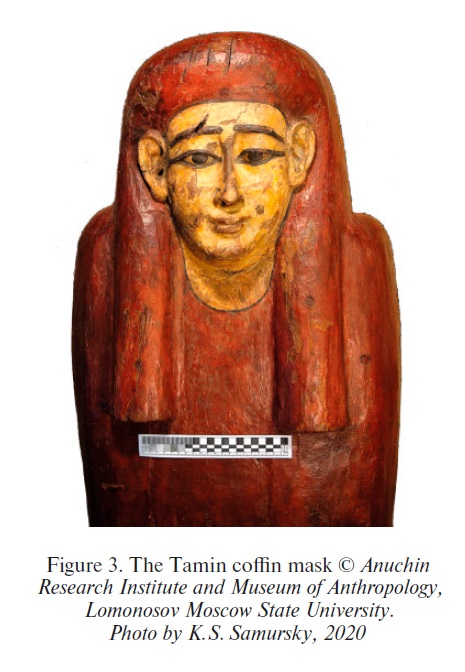

The mask was made in manner and style typical for early Ptolemaic times (Figure 3): three-part wig with two long streaks at the front; in the back the wig contours were not traced clearly or were erased. The face and the front streaks of the wig were cut from a single piece of wood. The oval face with rounded cheeks, small full chin turning into short neck. Regular face features: wide, almost strait eyebrows, circled with black ink, are turned down to the external corners of the eyes. The almond-shaped eyes are brought out by the traditional contour encircling also made in black ink. The long straight nose with narrow bridge and small wings. The full lips are curved in a faint smile hardly visible in the corners of the mouth. The face and neck are coated with ocher-yellow paint and emphasized by the black edging.

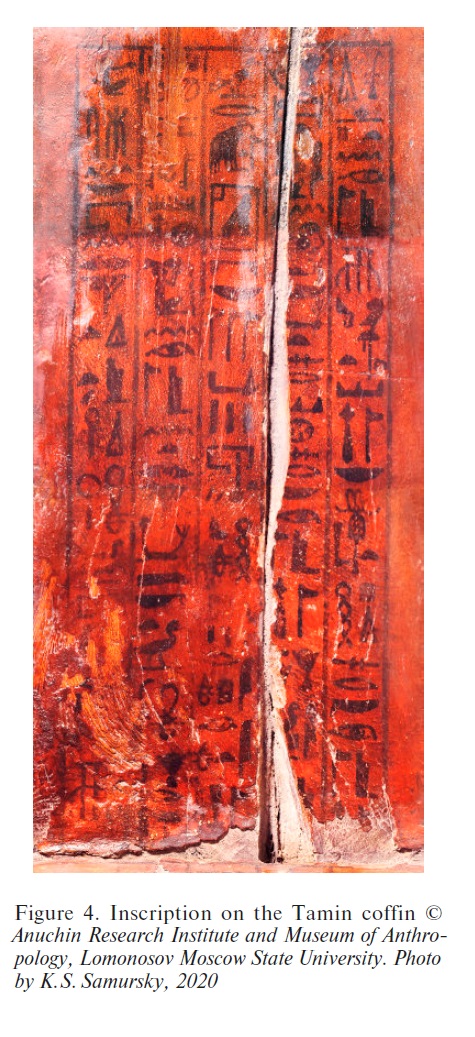

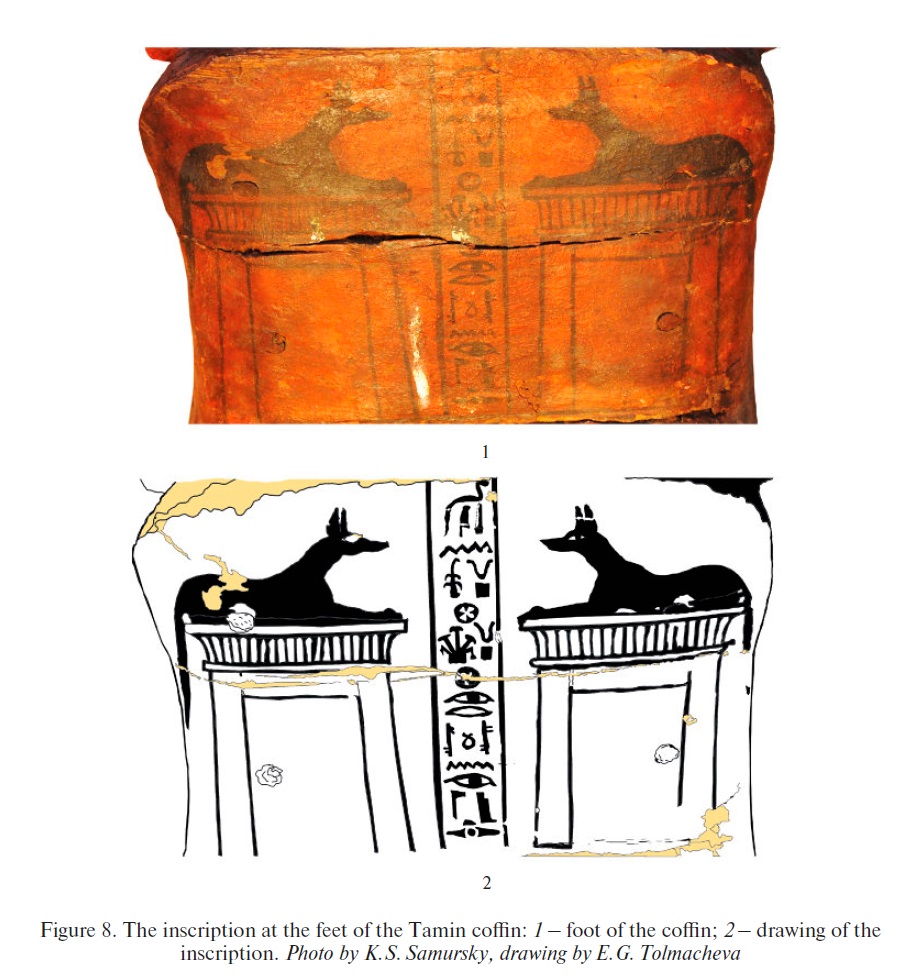

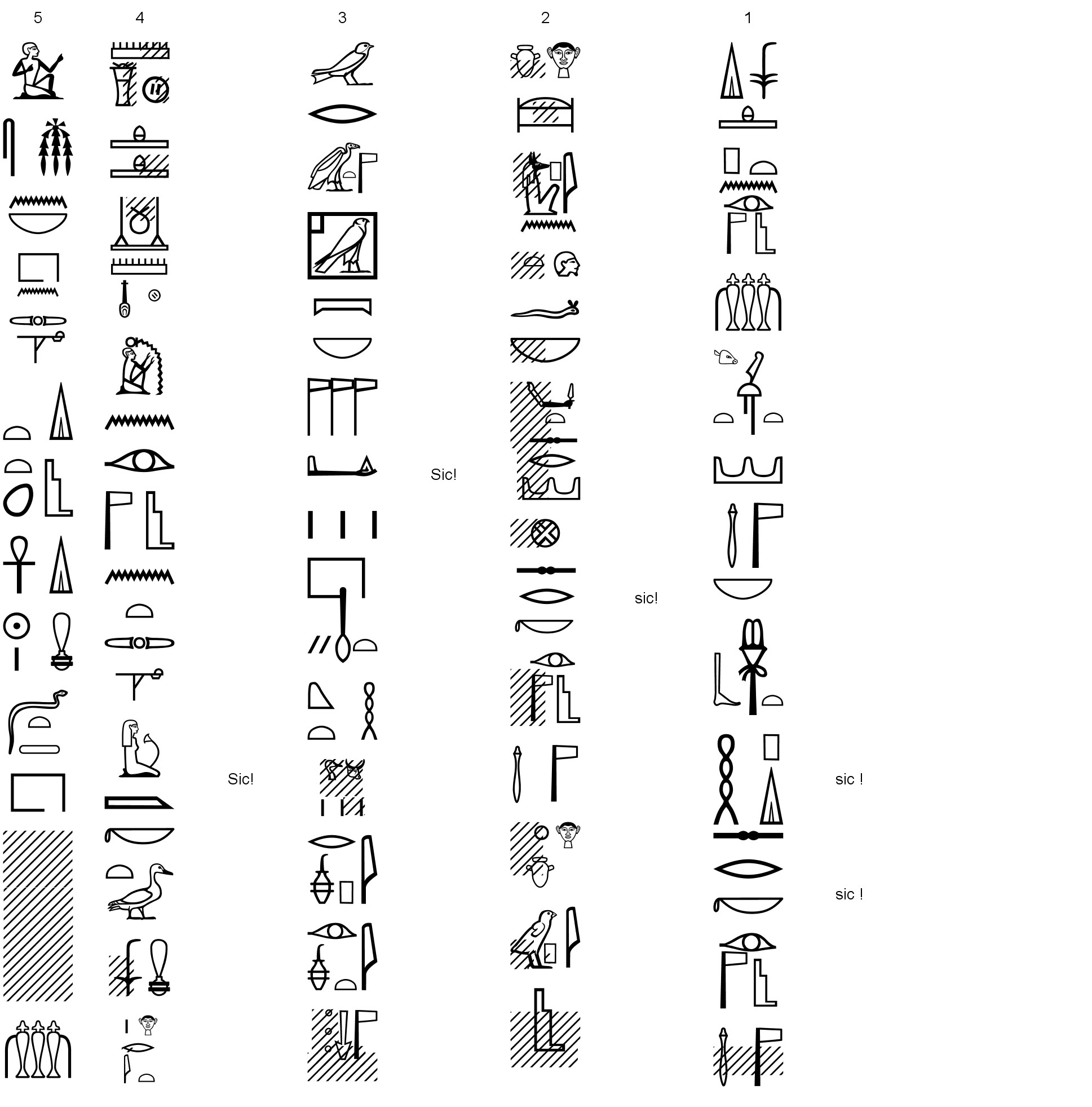

Five columns of the hieroglyphic inscription containing the traditional sacrificial formula hetep-di-nesu, names and titles are sized to fit the rectangular in the bottom past of the coffin lid (Figure 4). Also, on the foot board of the coffin there are two jackals laying on the shrine and a dedicatory inscription to god Upuaut.

The coffin bottom is complex, not decorated, primed from outside and coated with red-brown paint. The mummy, wrapped in several layers of partially disturbed burial shrouds and bandages, is laying in the coffin.

As far as our information goes, conservation of the coffin was performed in between 1939 and 194117. Unfortunately, no documentation about that conservation survived. However, based on comparison of the artifact, known to us from photographs prior to conservation, and its current appearance, it is possible to assume that the conservation professionals fixed joints of the boards, made up for the lost primer in places of the boards joints, strengthened the painting priming and paint layer. Pigment losses were tinted.

PARALLELS AND ANALOGUES

It can be seen from the description that Tamin's coffin characteristic feature is absence of paintings featuring numerous gods and mythological figures typical for Egyptian wooden coffins. Similar anthropoid wooden coffins with a minimum of paintings and short inscriptions containing, as a rule, the sacred formula and designation of the deceased and his ancestors appear in different regions of Egypt at the end of Late period18. Some of them are high-quality products made of fine wood, well-finished, often polished, having obvious artistic merits, such as for instance child's coffin from the British Museum dated to the end of Late period – beginning of Ptolemaic times19 or a fragment of Irtyru coffin with the sacrificial formula skillfully cut on the lid, dated to the same times, also from the British Museum20. As a rule, the best specimens of such coffins come from the metropolitan areas. An attempt was made, in the article by S. Moser devoted to the wooden coffin from the collection of Padua Museum of Anthropology, to define the provenance areal, dating and typological characteristics of one of the groups of Late lower-Egyptian, made of a single piece of wood, anthropoid coffins with laconic inscriptions21.

Less expensive versions of such coffins were made of wood of native species, as for instance, in Tamin's coffin case —of sycamore. Often they were not cut from a single piece of wood, but rather were complex products made of several boards connected with each other using of the tong-and-groove jointing. Manufacturing of such coffins was a local tradition in Akhmim in 4th–3rd centuries. Most of them were made of wood of native species for representatives of the so called middle class. J. Elias believes that refusal to cover the coffin's whole surface with images and texts was motivated by a desire to demonstrate the wood texture (if, for example, cedar was used for the coffin manufacturing). When craftsmen used the local wood, the surface was finished and coated with red-brown pigment which imitated the natural cedar color22. In Tamin's coffin case the surface was not only finished but also primed and paint-coated to smooth roughness and flaws in the wood and to hide gaps between the coffin's component parts.

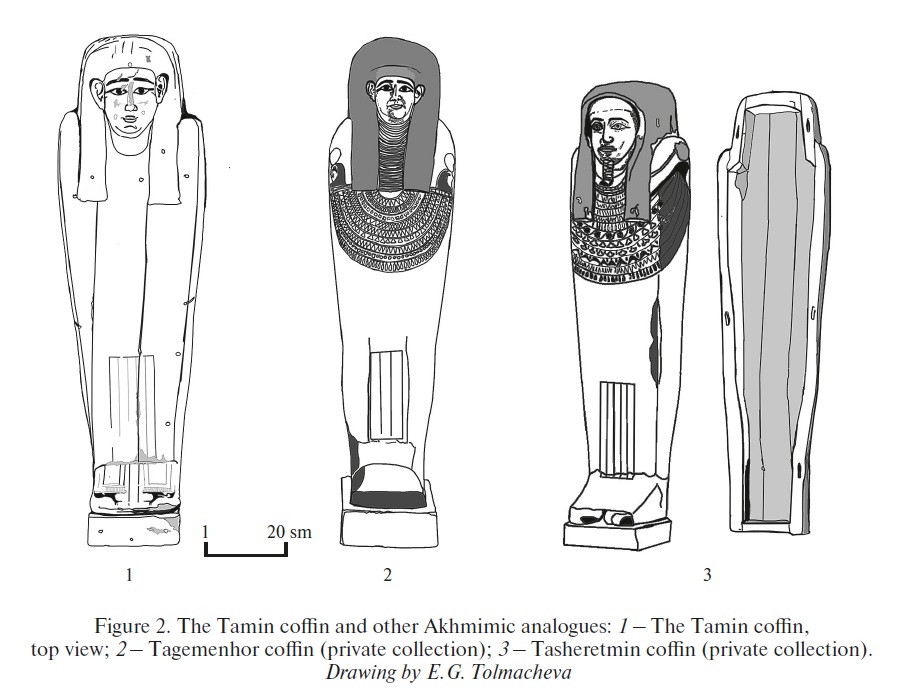

The German researcher R. Brech in her fundamental study of the Late Akhmimic coffins singled such coffins out in the special group D23 to which she attributed Tamin's coffin along with seven other objects from the international museums collections. Among characteristic features inherent to practically all coffins of this group, Brech pointed out the slightly straightened, on the sides, anthropoid shape, maximum width at the shoulders and sharp narrowing to the legs, absence of noticeable bulges on the coffin lid. The face image is slightly offset from the central axis on almost all coffins; this asymmetry is also noticeable in the case of Tamin's coffin. All male coffins have a beard with the exclusion of two coffins. The rectangular pedestal protrudes beyond the coffin "Legs" in the front part and on the sides24. The side pieces of the coffin's lower part are lower than the lid side pieces.

24. In Tamin's coffin case such pedestal is also present but does not protrude beyond the coffin's "legs".

The masks of almost all coffins are not decorated with diadems or other headdresses; the standard three-part wig is typical for them. The face complexion is fair, the faces of two masks are gold-plated. Only three out of group D coffins have usekh collar. The coffin surface is not decorated with images, only the laconic inscription with hepet-di-nesu formula and genealogy of the deceased. Spells from Book of the Dead are depicted on some of the coffins. Images of two jackals lying on the shrine and a short text also decorate the coffin's foot board in some cases25.

Based on the study of technological and iconographic features of some coffins from group D as well as paleography and linguistic usage in inscriptions on these coffins R. Brech dated the group broadly enough, practically to the whole period of Ptolemaic times26. Also, the author made an assumption that certain stylistic characteristics of group D coffins: smooth, three-part wig without additional decoration, gold-plated face27, deeply-put on necklace-collar, usekh-collar with falcon head and the Sun disks — distinguish it from other types of Akhmimic coffins (groups A, B and C) and appeared not earlier than in Ptolemaic times. R. Brech designated the protruding pedestal and image of two jackals lying on the sanctuary as the Ptolemaic features which were not so widespread although they could be met on the earlier coffins28.

27. Additionally, in case of Tamin this is less expensive imitation of gold plating.

28. Brech 2008, 167–168.

Taking into account the considerations of R. Brech about dating and stylistic features of that group of Akhmimic coffins to which Moscow Tamin's coffin belongs, we would like to present several other analogues. Firstly, it is necessary to mention the anthropoid coffin of a sistrum-player Tagemenhor (Figure 2,2) which was put on auction at Sotheby’s in 2019 (lot 64). G. Elias dates the coffin to 332-290 B. C.29 By its design, stylistic features and text characteristics, the coffin fully corresponds to criteria proposed by R. Brech for coffins of this group: anthropoid shape, protruding rectangular pedestal, long three-part wig without additional decoration, deep necklace and polychrome usekh-collar with images of Horus head and the Sun disk, gold-plated mask, red-brown color of the coffin itself. The coffin length is 192 cm. Tagemenhor's mask treatment: regular features of oval face with slightly rounded chin, straight going-down eyebrows, almond-shaped eyes; all resembling Tamin's mask. However, as opposed to Tamin's mask, Tagemenhor's mask has the wig which is much higher in the upper part, and the face itself is more miniature.

Sotheby’s website presents Tagemenhor's coffin photograph from 1905 catalogue where this inner coffin is shown next to external rectangular decorated coffin which fate is not known at present. Documentary evidence of existence of the external coffin makes it possible to assume that the burial set of Akhmimic coffins of Ptolemaic times included the external coffin apart from the inner coffin, and somewhere in private collection one more coffin could be stored.

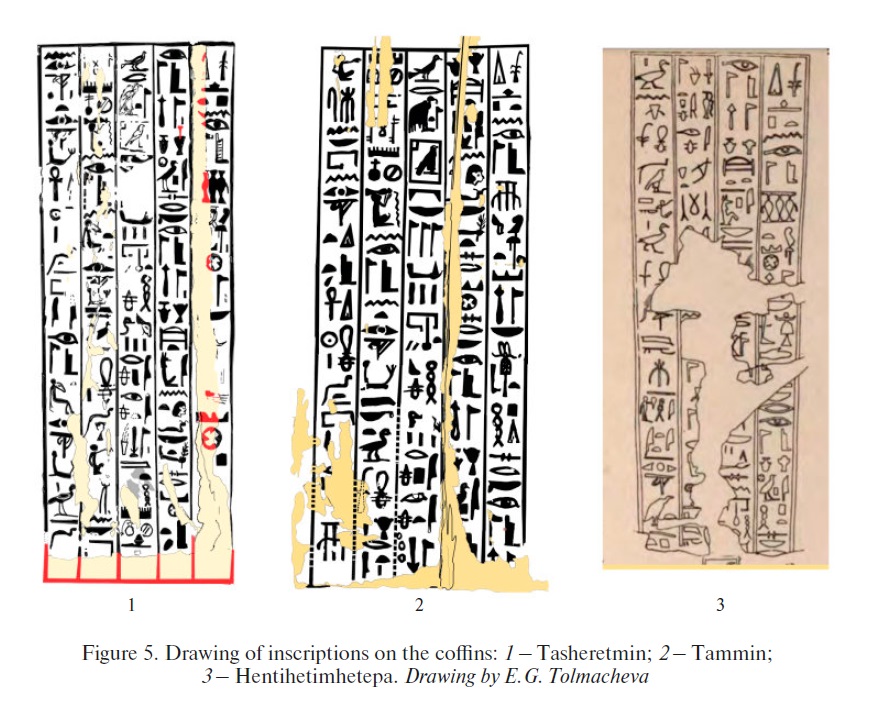

However, it is one more inner wooden coffin from a private collection put on auction at Bonhams auction house30 (Figure 2,3) which is of greatest interest from the point of view of Tamin's coffin study. Tasheretmin's coffin came from New York private collection where it was stored since 1983. Prior to that, it belonged to the private gallery of known American antique dealer Samuel Haddad who bought it in Egypt in the 1970s. New York coffin is a close analogue of Tamin's coffin in its design31, color, inscriptions placement, style and techniques used. However, Tasheretmin's coffin (female according to the inscription and name) has a man's beard by contrast with the Moscow coffin. Tasheretmin's coffin mask is made with great artistic skill, face looks, especially the eyes, attract attention because of their naturalism. Image of the polychromic usekh-collar on Tasheretmin's coffin, typical for many Akhmimic coffins of group D, can be mentioned amongst other differences. The inscription was made by black ink over ochre yellow background (Figure 5, 1)32. It is important to note a strong resemblance of inscriptions on Tamin's and Tasheretmin's coffins ( excluding names, small changes in sequence of some epithets and other small differences). We can safely assume that both inscriptions have the same prototype and, possibly, were made in the same shop. The auction cataloguers dated Tasheretmin's coffin to the period of XXVI-XXX dynasty (approximately 664-332 B. C.). It seems possible for us to make a cautious assumption that New York coffin is somewhat younger than that date and can be dated to the same early Ptolemaic times33 as Tamin's coffin. However, it is possible that Tasheretmin's coffin was made somewhat earlier than Tamin's one. Despite the obvious resemblance, the inscription text on Tasheretmin's coffin is a fuller version of the tentative prototype which can presumably be explained by the fact that the scribe who made the inscription could directly use the prototype which was already known in a distorted form by the period of time when Tamin's coffin was manufactured. Undoubtedly, other reasons of discrepancy between the texts on Tamin's and Tasheretmin's coffins are possible such as the customer expectations, erudition and attentiveness of the scribe who made those works. Thus, the discrepancy can be explained by other reasons rather than difference of times when the artifacts were manufactured. However, the fact of chronological and stylistic similarity of these two artifacts appears undeniable.

31. Coffins dimensions differ. Tasheretmin's coffin length is 169 cm.

32. Unfortunately, we did not have an opportunity to get acquainted with the artifact; however even careful examination of the photograph shows that the inscriptions were partially refreshed by the contemporary conservation professionals (the possible contemporary complements are shown in red in the trace drawing made bu us).

33. The publication Elias, Lupton 2019, 181 gives attention to some stylistic features of the usekh-collar decoration which supposedly indicate at such dating. Unfortunately, the publication authors missed out criteria of dating the ornament. This is why we can use their data only as indirect evidence.

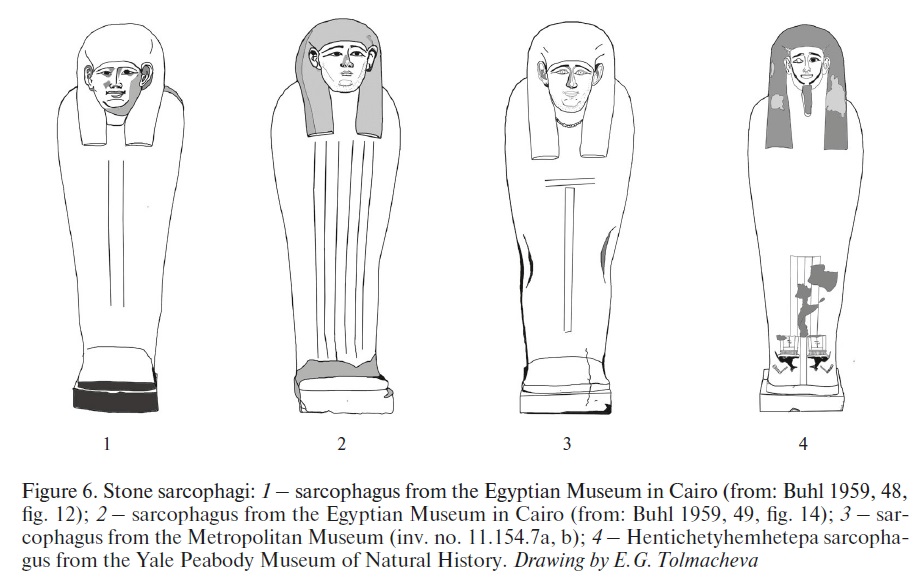

Is it possible to date Tamin's coffin inside group D more accurately? We shall try to give a more definite answer to this question after analysis of the inscriptions on the Moscow coffin. Herein, we would like to show some other stylistic parallels for the Moscow coffin. For this reason we shall turn to one more fairly large group of artifacts of Late and Ptolemaic times – to stone anthropoid sarcophagi34. Several types, differing in stylistic and technological characteristics and also having chronological and regional features, can be distinguished amongst these sarcophagi. The most interesting for our study are the sarcophagi singled out by the Danish researcher M.-L. Buhl in group E.

There is no single answer to the question about interrelation of the stone and wooden sarcophagi, if the wooden ones were cheaper imitation of the stone ones or else they were a special type which was evolving independently during Late and Ptolemaic periods. Most researchers take the view that the wooden coffins imitated contemporary, to them, stone sarcophagi35, and that is why there were no polychromic paintings on them. However, researchers also pay attention to the fact that not in every instance paintings are absent on the stone sarcophagi36. R. Brech questioned whether all wooden coffins were imitations of the stone ones. She supposed that, possibly, the inner coffins of group D could assume the function of the external ones37.

36. Moser 2019, 167.

37. Brech 2008, 170.

Anyway, we can speak of presence of certain parallels between the stone sarcophagi of group E (according to classification by M.-L. Buhl) and Tamin's coffin. Amongst the possible parallels it is necessary to list, in particular, the sarcophagi from the Cairo museum: E, a 1038 (Figure 6,1), E, а 1139 (Figure 6, 2), Е, а 740; from Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek: E, a1641; from The McManus: Dundee's Art Gallery & Museum: Е, а 2042; from the Metropolitan Museum: Е, в 2243 (Figure 6, 3), etc. M.-L. Buhl dates all these stone coffins, based on stylistic, palaeographical and other criteria, to the end of 3rd – the first half of this 2nd century B. C.44 which also can be one of the possible substantiations of the preliminary dating of Tamin's coffin based on the stylistic features. Unfortunately, M.-L. Buhl publication provides no clear criteria of dating of the published artifacts, that is why our conclusions can be only provisional.

39. Buhl 1959, 49, fig. 14.

40. Buhl 1959, 45, fig. 17.

41. Buhl 1959, 52, fig. 20.

42. Buhl 1959, 57, fig. 23.

43. Buhl 1959, 57, fig. 86.

44. Buhl 1959, 214–215.

Amongst the stone sarcophagi, not taken into account in the work by Buhl, the stone sarcophagus of priest smA.tj Khentikhetiemkhotep from the Peabody Museum of Natural History at Yale University 45 (Figure 6, 4) is of particular importance for dating and understanding of the inscriptions on Tamin's coffin. One can speak of an almost verbatim reproduction of the inscriptions’ texts (Figure 5, 1–3) despite certain stylistic and technological differences of two coffins, as is in the case of Tasheretmin's coffin inscription. Comparison of three texts under consideration leads us to the conclusion that there was some common prototype, a stereotyped text, which served as a model for all three artifacts. However, the inscriptions on Khentikhetiemkhotep's coffin, in all likelihood, contain a fuller version of this prototext. We shall discuss this issue in detail in comments to translation of Tamin's coffin texts, herein giving just one example. A wrong sequence of hieroglyphic signs in the name skr is noted in Tamin name inscription. The same mistake is noted in the same place in the inscription on Tasheretmin's coffin, but it is absent in the text on Khentikhetiemkhotep's coffin. On the whole, less variants of wrong spelling and distortions are noted in the inscriptions on Khentikhetiemkhotep's coffin as compared to Tamin's and Tashretmin's texts. Again, as in the case of comparison of the inscriptions on Tamin's and Tasheretmin's coffins, this fact can have several explanations; however we think that Khentikhetiemkhotep's coffin is the earlier.

Strangely enough, Khentikhetiemkhotep's coffin does not originate from Akhmim. He was found in tomb No. 7 in Abydos at the beginning of the 20th century46. Aside from a heavily damaged sarcophagus, the tomb also contained a funeral stele, which contained more details about Khentikhetiemkhotep and his ancestors47. Almost half a century later after the first publication of findings from tomb No. 7, Belgian researcher H. De Meulenaere , analyzing the funeral stele at the Roemer and Pelizaus museum in Hildesheim, managed to come up with a few theories directly relating to determing the origin of the owner of the Abydos tomb48. According to de Meulenaere , the stele from Hildesheim has multiple textual parallels with that of the priest Nesmin from the Field museum in Chicago (Inventory number 32169). However, if the circle of gods listed on the Chicago stele and set of toponyms undoubtedly show its Akhmim origins, then the Hildesheim stele can undoubtedly be said to belong the Abydos region. Moreover, the name of the owner of the Hildesheim stele was Neskhor49, just like the father of the owner of the Chicago stele, Nesmin. The Belgian researcher came to the conclusion that Neskhor and Nesmin were from the same family, which Khentikhetiemkhotep, our priest from Abydos also belonged to- his father was also called Neskhor. De Meulenaere offers the following hypothesis – the Abydos priest Neskhor had two sons- – Nesmin (owner of the Chicago stele) and Khentikhetiemkhotep (from Abydos tomb No. 7). At some point Nesmin moved to Akhmim, and his stele, in general resembling that of his father, begins to take on some Akhmim characteristics. The other son, Khentikhetiemkhotep, stayed in Abydos. On the basis of his study of the texts from all these monuments, H. de Meulenaere dated them to the beginning of the Ptolemaic era in 300 B.C.50

47. Randall-Maciver, Mace 1902, XXXIII. 3.

48. De Meulenaere 1969.

49. The first publishers read this name as Dzhutikhor (de Meulenaere 1969, 214).

50. De Meulenaere 1969, 220–221.

However, as we can see, it is possible to reconstruct another timeline of events, as well as a genealogical origin story for the characters in our story. Firstly, the name Neskhor is quite a common ancient Egyptian name. The Khentikhetiemkhotep from Abydos tomb No. 7 could well be the son of a different Neskhor, with no relation to the owner of the stele in the museum in Hildesheim. But even if de Meulenaere 's hypothesis was right, nothing in the text on Khentikhetiemkhotep's sarcophagus suggests unambiguously that he was from Abydos. Khentikhetiemkhotep's mother bore the title of the musician of Min, and his grandfather was named Nesmin. It would be completely logical to suggest the existence of a Akhmim families, two representatives of which, father and son (Neskhor and Khentikhetiemkhotep), moved to Abydos at different times. Another explanation is possible: Being closely connected to the priesthood of Min, Khentikhetiemkhotep (or his family) ordered the carving of a Akhmimic offering formula on his sarcophagus.

In any case, as we can see, the earlier sarcophagus of Khentikhetiemkhotep, dated to 300 B.C. by de Meulenaere can serve as terminus ante quem for Tamin's coffin.

So, the inscriptions for Khentikhetiemkhotep, and those of Tasheretmin (as far as they have been preserved) can served as a good source of understanding for translating the inscriptions of Tamin.

INSCRIPTIONS

As noted before, the basic inscription on Tamin's coffin is a traditional offering formula with multiple offerings, which the deceased was endowed with, who bore the name Tamin, traditional for the Akhmim priesthood – a theophoric name, an abbreviation of "Tanetmin" ("She who belongs to Min" (a servant of Min), tA-(n.t)-mn.w)51 (fig. 4; 5, 2). A particular characteristic of the inscriptions is that many of them had names and titles, lists of gods and their epithets, a set of those included in the ritual death offerings that clearly show their Akhmim origins52.

52. Similar incantations have been spotted on other Akhmim coffins and stele. For example, Elias 1996–2012; 2016, 4; Kamal 1905, 1 (stele 22001), 6 (stele 2205), 10 (stele 22009), 13 (22011), 26 (22025), 36 (22039), 37 (22040), 69–70 (22074), 107–108 (22123), 109 (22125), 114 (22133), 132–133 (22147), 140–141 (22152), 144 (22157) and others.

The title of the deceased is not directly mentioned in the inscriptions, but the first publications of the text suggested that she was jHjj.t, the musician Wb. I, 121.18) of Min53. He mother Taditiset bore the same title.

The question with regards to the name of Tamin's father remains open: due to the loss of the inscriptions here, a clear reading of the hieroglyphic signs is difficult, we can only talk about assumptions expressed with a greater or lesser degree of certainty. In their comments to the inscriptions O.D. Berlev and S.I. Hodjash put forward the hypothesis, according the which this group of signs (fig. 6) is read as "mj Hrj (Hr.t) jb"- "like the middle one" 54 (of three brothers) and such a veiled form points to the names of those who rebelled against the Ptolemies55. Other proof of their hypothesis regarding the royal origins of the deceased Tamin is the used of the epithet mj Raw D.t ("like Re eternally "), in the inscription, which comes after the name of the mother of the deceased and in preceding eras of Egyptian history was used in relation to pharaohs56. The authors expressed the idea that the late Tamin (or the one who wrote this text) allegorically proclaimed that her father belonged to the royal family and bore the same name as his middle brother, the pharaoh. The name of the reigning king was known by everyone, and any possible reader would know exactly who the inscription was talking about. The only three brothers of the royal family of the Ptolemaic era - the elder, middle and younger (thus the alleged father of Tamin, namesake of the middle brother, the pharaoh), and probably even related to the Akhmim priesthood, according to O.D. Berlev and S.I. Hodjash, were the leaders of the anti-ptolemaic revolts, Horwennefer, Ankhwennefer and his younger brother with the same name57.

55. Berlev, Hodjash 1998, 35.

56. Berlev and Hodjash also point out that the epithet was was placed after the name of the mother of the deceased Tamin by mistake and should come after the name of the father, thus allegorically designated the namesake of the rebellious pharaoh (Berlev, Hodjash 1998, 35).

57. Berlev, Hodjash 1998, 34–35.

How closely do these hypotheses match reality? The text of the inscription and its composition make mention of certain characters and certain orthographic and paleographic features as well as stylistic and technological characteristics of Tamin's coffin that allow us to date it to the early Ptolemaic era and hypothesise that it was made in Akhmim. The question of how much the text of the inscription on the coffin could reflect the peripheries of the Egyptian uprising of 205-186. B.C., is far from unambiguous. Most of all it's connected with the fact we simply don't know much about this period of Egyptian history58. Greek sources, such as Polybius (V 107.1; XIV 107.1) are short and biased. The Egyptian narrative, excluding Demotic and Greek documents, which mentioned the names and years that the rebellious pharaohs ruled and some of the indirect consequences that followed the spread of the uprising across the country, and also some temple inscriptions59, has been all but lost. One of the most famous Egyptian sources, the Rosetta stone (196 B.C.) talks of Ptolemy's victory over the rebels in the north. Based on a comparison of a few documents, researchers were able to approximately reconstruct the main outline of the events of the uprising: the beginning in 207/206 B.C. in Edfu, the restoration of Egyptian power over most of the country, the coronation of the local Egyptian pharaoh Horwennefer60 in 205 B.C. in Thebes, the death of Horwennefer in 200 / 199 B.C. and the accession to the Theban throne of Ankhwennefer in 199 B.C., and finally, the final defeat of the latter in 186 B.C. by the Ptolemaic commander Komanos. However we know almost nothing about the personalities of the rebel kings, their exact origins, or their families. There is not one single mention in any written monument we know of about them (apart from the hypothetical "middle brother" of hypothetical royal blood in the sacrificial formula of the Moscow coffin) that allows us to speak with certainty of Tamin's royal connections. Moreover, the authors of this article do not know of a single example of such "allegorical" naming of relatives in funeral rites.

59. Among the inscriptions on the temple of Horus in Edfu, Egyptian graffiti in the funeral temple of Seti I in Abydos (Pestman, Quaegebeur, Vos 1977, no. 11), the so called second decree of Ptolemy V on the victory over the rebels, carved on the walls of the temple in Edfu (Müller 1920, 59–88).

60. The names of the pharaohs of the so-called anti-ptolemaic dynasty (Horwennefer and Ankhwennefer) shared a few of common characteristics: they contain one of the main epithets of Osiris - "wnnefer" ("abiding in goodness"). It's probable that these kings had southern Egyptian or even Nubian roots.

Let us look at the translation and textual analysis of the inscription (fig. 4; 5 2).

- Offering formula at the feet of the coffin lid

Transliteration: (1) Htp-dj-ns.w n Wsjr xntj jmn.tjt nTr aA nb AbD.w PtH-%kr-Wsjr nTr aA (2) Hrj-jb STjj.t Jnp.w tp.j =f nb-(tA?)-Dsr %kr-Wsjr nTr aA Hrj-jb Jp.w [A]s.t (3) wr.(t) mw.t nTr @w.t-Hr.w nb.(t) p.t ntr.w dj=w pr.t-xr.w t Hnq.t jH.w Apd.w jrp jrT.t snTr (4) mnx.t Ss [Htp.w ?] x.t nfr.(t) wab.(t) n Wsjr n &A-Mn.w mAa.(t)-xr.w sA.t mj n(n) @r(j)-rtj (5) ms n nb.(t) pr n(t) Mn.w &A-dj-As.t dj anx mj Raw D.t pr.j (?) [...]xn.t

Translation: (1) An offering given by the king (to) Osiris , Foremost of the Westerners, the great god, the lord of Abju (Abydos), Ptah-Sokar-Osiris, the great god, (2) one who is in the shrine-STjj.t, to Anubis who is upon his , lord of the sacred land, Sokar-Osiris, the great god, who dwells in Ipu (Akhmim), Isis (3), the great, the mother of gods, Hathor, the lady of heaven, the mistress of gods.

That may give invocation offerings consisting of of bread, beer, oxen, fowls, wine, milk, incense, (4) , [Offerings?] Clothing and alabaster vessels, beautiful and pure things to Osiris--net-Min, true of voice, , a daughter of the same rank Kherireti (?), born to the lady of the house , the < the sistrum-player > of Min, Taditiset, (to whom) life is given like Re eternally . This leaves (?) [...].

Comments.

To part 1.

Htp-dj-ns.w - O.D. Belerv and S. I. Hodjash supposite that the beginning of the text is formulated according to the standard beginning of a offering formula on a funeral stele. Taking into account the similarity between the memorial stelae texts from Greco-Roman times and the inscriptions on the coffins, which could well have been compiled according to a single template, this is not too surprising.

Wsjr- is similar to a spelling of the name of Osiris61, which appears in private inscriptions in the era of the XXV dynasty and is found up to the Ptolemaic era.

xntj jmn.tjt nTr aA nb AbD.w is the standard following for epithets to Osiris, which is seen on many coffins and funeral stelae. Could the mention of Abydos point to the Abydos origins of the coffin? The answer to the question is not so simple, if you remember de Meulenaere's hypothesis regarding the Abydos origins of Khentikhetiemkhotep's family, and how the inscription on his sarcophagus is from the same template as on Tamin's. However, the study of the text of the inscription on the Tamin’s coffin, the sequence of mentioning the gods and offerings, and finally, the stylistics of the coffin itself rather testify to it belonging to the Akhmim circle of monuments.

PtH-%kr-Wsjr- in the text of the inscription there is an incorrect sequence of hieroglyphs in the name skr. This same mistake is present in the same place in the inscription on Tasheretmin's coffin, but not on Khentikhetiemkhotep's62, which allows us to date it earlier than the others.

To part 2.

The epithet Hrj-jb STjj.t is a standard epithet for Ptah-Sokar-Osiris in many Akhmim texts from the Ptolemaic era63.

Jnp.w tp.j =f - in this place on Tamin's coffin the text has been lost, so it is not clear if the hieroglyph here should be Dw or t, however in the same place on Tasheretmin's coffin it clearly says t. On Khentikhetiemkhotep's sarcophagus this epithet is skipped or is on a missing part of the inscription.

…nb-(tA?)-Dsr – O. D. Berlev and S.I. Hodjash offer this reading of the whole phrase: "Anubis, who is upon his hill, lord of the Sacred Land"64 . The text contains an unusual spelling of "lord of the sacred land", the epithet to Anubis, (LGG III, 774-775; see. Wb. V, 228.1). In this inscription the hieroglyph tA

. The text contains an unusual spelling of "lord of the sacred land", the epithet to Anubis, (LGG III, 774-775; see. Wb. V, 228.1). In this inscription the hieroglyph tA  is missing, which gives reason to believe that here they meant to write nb-Dsr.t (LGG III, 799). However, it is worth noting that the sign t

is missing, which gives reason to believe that here they meant to write nb-Dsr.t (LGG III, 799). However, it is worth noting that the sign t , which in this case would act as the end of the word Dsr.t, has shifted closer to the beginning of the phrase. This also shows the presence of the determinative for city (

, which in this case would act as the end of the word Dsr.t, has shifted closer to the beginning of the phrase. This also shows the presence of the determinative for city ( ). A similar spelling is seen on the Tasheretmin sarcophagus. However on Khentikhetiemkhotep's sarcophagus, despite the damage, the epithet nb-tA. wj can be seen, one of the variant ways to write the standard nb-tA Dsr. It can be presumed that on Tamin's sarcophagus, and on Tasheretmin's, there is a local spelling variant seen on a lot of epithets to Anubis nb-tA-Dsr, where the hieroglyph t is used instead of the standard tA.

). A similar spelling is seen on the Tasheretmin sarcophagus. However on Khentikhetiemkhotep's sarcophagus, despite the damage, the epithet nb-tA. wj can be seen, one of the variant ways to write the standard nb-tA Dsr. It can be presumed that on Tamin's sarcophagus, and on Tasheretmin's, there is a local spelling variant seen on a lot of epithets to Anubis nb-tA-Dsr, where the hieroglyph t is used instead of the standard tA.

Jp.w- this mention of Ipu ( Akhmim), along with the standard set of gods and praises which are characteristic of the Akhmim inscriptions, indicates the origin of the coffin.

To part 3.

nb.(t) p.t – the hieroglyph nb is most likely to be read twice: nb.(t) p.t ntr.w. There are gaps in this place on Tasheretmin's and Khentikhetiemkhotep's sarcophagi.

Hnq.t- The names of all the drinks included in the list of offerings are written with the same determinative, W20 , which is another characteristic of the simplified Ptolemaic spelling or an individual feature of the inscription. In the texts on Tasheretmin's and Khentikhetiemkhotep's coffins there is a similar spelling. The word jrT.t "milk" (Wb. 1, 117.1–5) is usually written with a determinative

, which is another characteristic of the simplified Ptolemaic spelling or an individual feature of the inscription. In the texts on Tasheretmin's and Khentikhetiemkhotep's coffins there is a similar spelling. The word jrT.t "milk" (Wb. 1, 117.1–5) is usually written with a determinative . To part 4.

. To part 4.

- as far as can be seen, the standard mrH.t " sacred oil" (Wb. 2, 111.1–10) for lists of offerings to the dead was skipped on the Moscow coffin. In the list of offerings on Khentikhetiemkhotep's sarcophagus, the sacred oil is written in the standard way, but the scribe obviously made a mistake on Tasheretmin's while writing mrH.t, changing the sign at the beginning 'mr' U6 to 'm'

U6 to 'm' Aa15. …[Htp.w ?]- the standard sequence in the list of offerings includes alabaster vessels and clothing (Ss mnx.t), and it's exactly these things that are mentioned on Khentikhetiemkhotep's sarcophagus

Aa15. …[Htp.w ?]- the standard sequence in the list of offerings includes alabaster vessels and clothing (Ss mnx.t), and it's exactly these things that are mentioned on Khentikhetiemkhotep's sarcophagus (Wb. 2, 87.16) and on the second inscription on the feet of the Moscow coffin, however on this part of Tamin's coffin and on Tasheretmin's we see a slightly different orthography. Also noteworthy is the use on Tasheretmin's and Tamin's coffins of the sign

(Wb. 2, 87.16) and on the second inscription on the feet of the Moscow coffin, however on this part of Tamin's coffin and on Tasheretmin's we see a slightly different orthography. Also noteworthy is the use on Tasheretmin's and Tamin's coffins of the sign  instead of the sign

instead of the sign  . The probable 65

. The probable 65 use of the word Htp.w (offerings) in the text of the list also raises questions, as this word usually goes together with Df.Aw (provisions), but in this case in the list of offerings, the word Df.Aw isn't there66

use of the word Htp.w (offerings) in the text of the list also raises questions, as this word usually goes together with Df.Aw (provisions), but in this case in the list of offerings, the word Df.Aw isn't there66 (Kamal 1905, 13)..png) .

.

x.t – a symbol  , which is used instead of

, which is used instead of  , in all likelihood should be read twice: at the end of the word mnx.(t) "clothing" and as a separate word x.(t) "things".

, in all likelihood should be read twice: at the end of the word mnx.(t) "clothing" and as a separate word x.(t) "things".

n Wsjr- both in the inscriptions on Tamin's and Tasheretmin's coffins, the word kA is skipped after the preposition n, which means it is not the standard collocation "For the Ка" of Osiris-Tamin.

Wsjr n &A-Mn.w – O.D. Berlev and S.I. Khodzhash drew attention to the use in this case of the formula Wsjr n NN67, in which n is the index of the indirect genitive68.

68. See Smith 2006; 2012.

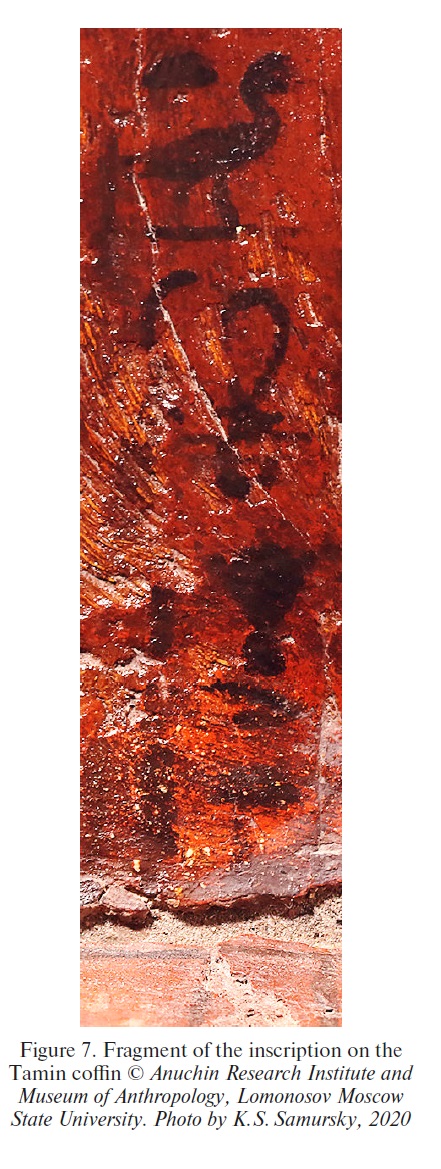

sA.t mj n(n) @r(j)-rtj – here we are dealing with a fragment central to understanding the inscription. Unfortunately, as we have already noted, the preservation of the inscription in this place is poor. Due to a defect in the wood and a very thin layer of preparatory primer, the paint layer is partially lost. In their comments to the inscriptions O. D. Berlev and S. I. Khodzhash saw the phrase "mj Hrj (Hr.t) jb" here and came to far-reaching conclusions about the monument's connection with the history of the Egyptian revolt against the Ptolemaic dynasty. However, (figure 7) an examination of the text shows that what we have before us is most likely the use of the title mj n(n) (Wb. 2, 37.11: "of the same (title ) as"), which is used to show that the title of the father is similar to that of the son, and the name of the father himself, in this case without the title. The title mj nn is often found on Ahimi monuments69 . A peculiarity of the inscription on the Tamin coffin, as well as on two other similar monuments (the Tasheretmin and Hentikhetihetaepa sarcophagi), is the orthography (the form mj n

. A peculiarity of the inscription on the Tamin coffin, as well as on two other similar monuments (the Tasheretmin and Hentikhetihetaepa sarcophagi), is the orthography (the form mj n instead of mj nn

instead of mj nn ). We also know of no other examples (besides the inscription on the sarcophagus of Tasheretmin) of the use of this title in relation to the father of a daughter rather than a son. The poor state of preservation of the text in this place makes it impossible to offer a definite reading of the father Tamin's name, but we can only assume that it is a distorted spelling Hr(j)-jr.t70

). We also know of no other examples (besides the inscription on the sarcophagus of Tasheretmin) of the use of this title in relation to the father of a daughter rather than a son. The poor state of preservation of the text in this place makes it impossible to offer a definite reading of the father Tamin's name, but we can only assume that it is a distorted spelling Hr(j)-jr.t70 as j + r is given by Ranke: Ranke 1935, 41. J. Elias mentions that the name hr-jr.t is one of the most common Akhmimic male names (Elias 2016, 6)]]] или Hr(j)-rtj. Such a form is not recorded in G. Ranke's dictionary, but various name variants beginning with Hr(j)- or the name rtj71

as j + r is given by Ranke: Ranke 1935, 41. J. Elias mentions that the name hr-jr.t is one of the most common Akhmimic male names (Elias 2016, 6)]]] или Hr(j)-rtj. Such a form is not recorded in G. Ranke's dictionary, but various name variants beginning with Hr(j)- or the name rtj71 are known.

are known.

To column 5.

nb.(t) pr title nb.(t) pr is one of the most common female titles. According to J. Elias, this title implies having one's own household, separate from the temple household, which allowed one to earn one's own income, unrelated to the performance of temple services72.

– in the text of the stele the title Tamin is omitted, but O.D. Berlev and S.I. Khodzhash have suggested that what is meant is the standard Akhmimic female priesthood title jHjj.t (Wb. 1, 121.18)73.

dj anx mj Raw D.t – the phrase dj anx mj Raw D.t used here served as the main argument of the first publishers of the sarcophagus in favor of the royal origin of Tamin's parent. However, R. Brech provides several examples of the use of such an epithet in relation to individuals74. Exactly the same epithet is inscribed on the sarcophagus of Tasheretmin (Figure 5, 1).

The end of the inscription has barely survived. Probably by analogy with the inscription on the coffin of Tasheretmin, it referred here to the Ba of the deceased. However, it is possible that the typical offering formula was interrupted halfway through due to lack of space on the inscribed columns.

Transliteration:

Dd md.w jn wp- SmA wp- mH.w jr=(j) Ss mnx.t n Wsjr tA-mn.w

Translation. The words spoken by the Up(uaut) of the Upper Egypt and the Up(uaut) of the Lower Egypt: "I make alabaster vessels and garments for Osiris-Tamin.

Commentary.

wp- SmA wp- mH.w – a similar way of writing the name of the god Up(uaut) of Upper Egypt (LGG II, 347, Nr. 73) and Up(uaut) of Lower Egypt (LGG II, 345, Nr. 39) is recorded only in a similar inscription on the sarcophagus of Hentikhetihemhotep.

MUMMY SWADDLING CLOTHS

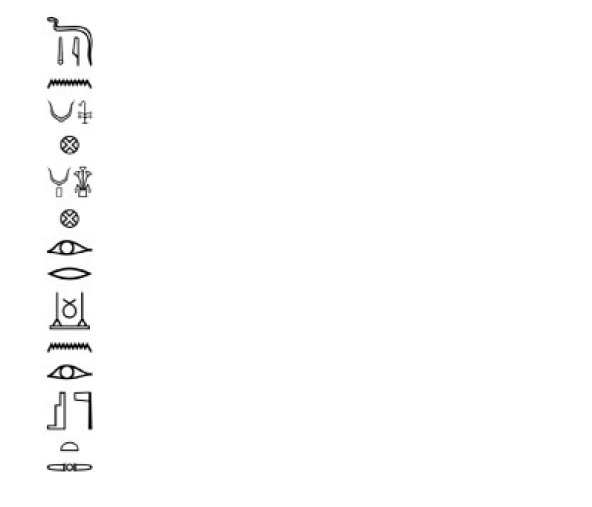

The Tamin Mummy, in a ruined state, is in a coffin75 (Fig. 9). At the mummy's feet there are two "binders" twisted from grass, the functional purpose of which can only be a matter of conjecture. The authors of the article believe that they were put under the layers of burial bandages to add volume. However, where did it happen: in ancient Egypt during the mummification, in modern Egypt in an antique shop to give the mummy a more "marketable" look or already in Russia in the process of preparing the mummy for display – we probably will never know76. The original bandage layers are damaged, but despite this, we can roughly reconstruct the layer-by-layer order of the bandage, determine the material and quality of the bandages and shrouds.

76. The analysis of plant remains was carried out at the Department of Geobotany, Lomonosov Moscow State University, by leading researcher V.E. Fedosov. According to his conclusion, "plant remains were found in the coffin, which were attributed to 3 species of the cereal family (Poaceae) — Dactylis, Alopecurus and Secale, as well as Calliergonella cuspidata moss. Unfortunately, the state of inflorescences and the vegetative sphere of plants does not allow us to identify cereals to species, and the distribution of genera to which they are assigned is wide enough. These groups, like the moss Calliergonella cuspidate, occur both in arid ecosystems of the Mediterranean (so that their occurrence in Egypt in the past is not excluded) and in humid conditions of middle Europe, taking into consideration the European part of Russia. Therefore, their study does not provide information on the history of the object from the collection of the Museum of Anthropology of Moscow State University.

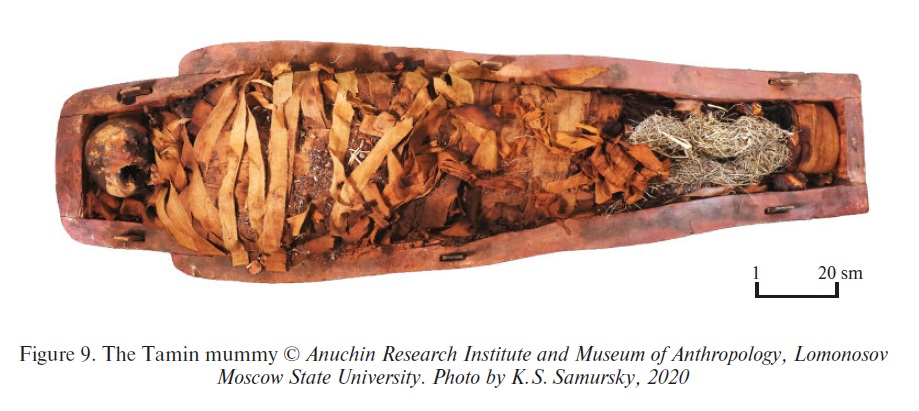

During visual examination, we took several samples of textiles from different layers of mummy bandages (Fig. 10). The nature of the textile fibre was determined by microscopy, and the textiles were also studied using a textile magnifying glass77. The following technical characteristics were obligatory for description: type of textile object, nature of textile fibers, spinning characteristics (twist, direction and angle of spin, diameter of yarns), characteristics and weaving techniques (warp and weft count, weaving details etc.), presence of decoration and traces of repair.

Since ancient times, flax has been the basis of ancient Egyptian textile production, so it is no coincidence that in all the samples that we selected for the study we identified linen fiber. As with most Egyptian textiles, the textiles of the Tamin mummy bandages are S-twist warp-faced tabby , of medium quality. It can be assumed that one or two clothes with approximately the same technical characteristics were used for bandages: with a warp count of 24-20 yarns per cm2 and about 10-12 yarns in the weft. angle of spin is loose or medium, the diameter of warp yarns is 0.2-0.3 mm, weft — 0.2-0.4 mm.

In total, there are about 20 layers of bandages on the mummy using medium width bandages (4-7 cm). Several larger fragments of good quality cloth (34-32 threads per cm2 in the warp, 14-15 in the weft, medium angle of spin) were found on top of the mummy, one of which had its edge (probably, the starting edge of the cloth) sewn with a closed hem; the self-bends were also fixed. Such technological characteristics suggest that these are fragments of the burial shroud that once covered the mummy placed in the coffin.

A fragment was found at the feet of the mummy, presumably the mummy's padding fabric. It shows signs of wear and tear, probably a fragment of clothing or household textiles torn into bandages. All other bandages and fragments of the shrouds do not show traces of wear or seam fragments, which indicates a certain affluence of the family of the deceased, since for ordinary buried people, as a rule, old clothes or household textiles were used to make bandages78. However, neither the quality of the fabric of the bandages nor the characteristics of the burial shroud that covered the mummy can be compared with the products of the royal workshops.

The technological characteristics of the fabrics are typical of ancient Egyptian textiles and allow us to date them no later than the Ptolemaic period.

Therefore, based on the translation and analysis of the inscriptions on the Tamin coffin, as well as comparing these inscriptions with similar texts of the Tasheretmin and Hentikhetihemkhotep sarcophagi, we can agree with the assumption of the first publishers of the Moscow sarcophagus of its Akhmim origin.

The characteristic stylistic and paleographic features of the inscription, the language, the errors it contains, the titles and epithets also allow us to place its date in the Ptolemaic era. However, neither in the text of the inscription, nor in other sources known to us, is there any indication of its connection with the events of the Antiptolemaic revolt of Horwennefer and Ankhwennefer. Proposed by O.D. Berlev and S.I. Hojdash's reading of "mj Hrj (Hr.t) jb" does not correspond to the text of the inscription and cannot be an indication of the mythical middle brother Pharaoh. The use of the royal epithet dj Raw D.t is not a direct reference to the belonging of the deceased or her family to the ruling dynasty and is also found in Ptolemaic times on other monuments belonging to private individuals, in particular in a similar inscription on the Tasheretmin coffin.

Moreover, neither the quality of the workmanship, nor the stylistic features and appearance of the Tamin coffin, nor the quality of the fabrics used to bandage the deceased allow us to speak of its possible belonging to a high-ranking owner, let alone a member of the royal family. The fact that the owner of the coffin most likely belonged to the rank and file Akhmim priesthood, the so-called local middle class, is also evidenced by her names and probable title, as well as the names and titles of her parents (the mother was a musician of Min, the father – without a title).

Comparison of the Tamin’s coffin with other similar monuments, in particular with the Tasheretmin and Khentikhetiemkhotep sarcophagi, as well as a group of stone sarcophagi, allows us to propose a potential date of the Moscow monument from the late 3rd century to the first half of the 2nd century B.C. Of course, this dating is speculative, as it is partly based on parallels dated by other researchers. Some of the stylistic and technological characteristics of the Tamin’s coffin are inherent in monuments dating to the end of the Late Period. However, it is the combination of the complex of stylistic and technological features highlighted, for example, by R. Brech for coffins of group D: anthropoid shape, protruding rectangular pedestal, long three-part wig without additional ornaments, deep necklace and polychrome breastplate, red-brown colour of the coffin, with the characteristic stylistic and paleographic features of the text of the inscriptions on the coffin (for example, the presence of some distortions and errors, selection of names and epithets) allows us, however, to settle on an early Ptolemaic date. A later date seems unlikely, since the texts do not have the typical late Ptolemaic set of paleographic, stylistic, and other features.

Библиография

- 1. Ancient Resource Auctions 2015: Ancient Resource Auctions. Auction 38: Fine Ancient Artifacts, 08 March 2015. Montrose (CA).

- 2. Berlev, O., Hodjash, S. 1998: Catalogue of the Monuments of Ancient Egypt from the Museums of the Russian Federation, Ukraine, Bielorussia, Cau-casus, Middle Asia and the Baltic States. Fribourg–Göttingen.

- 3. Bonhams 2014: Bonhams Auctions. Antiquities, Thursday 02 October 2014. London.

- 4. Brech, R. 2008: Spätägyptische Särge aus Achmim: eine typologische und chronologische Studie. (Aegyptiaca Hamburgensia, 3). Gladbeck.

- 5. Buhl, M.-L. 1959: The Late Egyptian Anthropoid Stone Sarcophagi. København.

- 6. Elias, J. 1993: Coffin Inscriptions in Egypt After the New Kingdom: A Study of Text Production and Use in Elite Mortuary Preparation. PhD Thesis, University of Chicago.

- 7. Elias, J. 1996–2012: Examination of Three Egyptian Coffins in the Buffalo Museum of Science. (Revised in 2012). (AMSC, Research Paper, 96–1). Carlisle.

- 8. Elias, J. 2016: Overview of Lininger A06697, an Akhmimic Mummy and Coffin at the University of Nebraska, Lincoln. (AMSC, Research Paper, 16–3). Carlisle.

- 9. Elias, J. 2019: Condition report. An egyptian polychrome and gilt anthro-poid inner coffin of the sistrum-player Ta-gem-en-hor. On-line publication. URL: https://www.sothebys.com/en/buy/auction/2019/ancient-sculpture-and-works-of-art-2/an-egyptian-polychrome-and-gilt-anthropoid-inner; дата обращения: 10.05.2021.

- 10. Elias, J., Lupton, K. 2019: Regional identification of Late Period coffins from Northern Upper Egypt. In: H. Strudwick, J. Dawson (eds.), Ancient Egyptian Coffins: Past, Present, Future. Oxford, 175–184.

- 11. Gauthier, H. 1931: Les personnel du dieu Min. Le Caire.

- 12. Kamal, A. 1905: Stèles Ptolémaiques et Romaines. T. I. (CG, no. 22001–22208). Le Caire.

- 13. Krol, A.A. 2017: [New archive materials concerning the Egyptian antiquities offered to Russia by Khedive Abbas II]. Vestnik drevney istorii [Journal of Ancient History] 77/4, 991–1008.

- 14. Крол, А.А. Новые архивные материалы о египетских древностях, подаренных хедивом Аббасом II России. ВДИ 77/4, 991–1008.

- 15. Krol, A.A. 2019: [Archival materials on the Egyptological collection of the Anuchin Research Institute and Museum of Anthropology of the Lomonosov Moscow State University]. Vestnik drevney istorii [Journal of Ancient History] 79/3, 754–771.

- 16. Крол, А.А. Архивные материалы о формировании египтологиче-ской коллекции НИИ и Музея антропологии МГУ им. М.В. Ломоносова. ВДИ 79/3, 754–771.

- 17. Leahy, A. 1979: The name Osiris written . Studien zur Altägyptischen Kultur 7, 141–149.

- 18. McGing, B. 1997: Revolt Egyptian style: internal opposition to Ptolemaic rule. Archiv für Papyrusforschung und verwandte Gebiete 43/2, 273–314.

- 19. Meulenaere, H. de 1969: Un prêtre d’Akhmim à Abydos. Chronique d’Égypte 44 (88), 214–221.

- 20. Moser, S. 2019: The coffin of the Anthropology Museum in Padua and others. A peculiar type of Late to Ptolemaic Period wooden anthropoid coffins. In: H. Strudwick, J. Dawson (eds.), Ancient Egyptian Coffins: Past, Present, Future. Oxford, 157–167.

- 21. Müller, W.M. 1920: Egyptological Researches III. The Bilingual Decrees of Philae. Washington.

- 22. Orfinskaya, O.V., Tolmacheva, E.G. 2016: [Ancient textiles from the tomb of Thay (TT 23): considerations on elaborating of approaches and preliminary results of studies]. Egipet i sopredel’nye strany (elektronnyy zhurnal) [Egypt and Neighboring Countries (Online Journal)] 4, 64–110.

- 23. Орфинская, О.В., Толмачева, Е.Г. Предварительные результаты исследования текстильного материала из фиванской гробницы Чаи (ТТ 23): к вопросу о выработке методики изучения древнеегипетского археологического текстиля. Египет и сопредельные страны (электронный журнал) 4, 64–110.

- 24. Orfinskaya, O.V., Tolmacheva, E.G. 2018: [Archaeological textile as a source on social, ethnic and religious identity of the Egyptian provincial population in the Graeco-Roman period: by evidence from Deir al-Banat necropolis]. Stratum plus 4, 219–237.

- 25. Орфинская, О.В., Толмачева, Е.Г. Археологический текстиль и его значение при решении вопросов социально-этнической и религиоз-ной принадлежности населения египетской хоры в грекоримское время: по материалам некрополя Дейр аль-Банат (Фаюм). Stratum plus 4, 219–237.

- 26. Pestman, P.W. 1995: Haronnophris and Chaonnophris: two indigenous pharaohs in Ptolemaic Egypt (205–186 B.C.). In: S.P. Vleeming (ed.), Hundred-Gated Thebes. Acts of a Colloquium on Thebes and the Theban area in the Graeco–Roman Period. (Papyrologica Lugduno–Batava, 27). Leiden–New York–Köln, 101–137.

- 27. Pestman, P.W., Quaegebeur, J., Vos, R.L. 1977: Recueil de textes démotiques et bilingues. Vol. I. Transcriptions. Vol. II. Traductions. Vol. III. Index et planches. Leiden.

- 28. Randall-Maciver, D., Mace, A.C. 1902: El Amrah and Abydos. London.

- 29. Ranke, H. 1935: Die ägyptischen Personennamen. Bd. I. Verzeichnis der Namen. Glückstadt.

- 30. Recklinghausen, D. von 2018: Die Philensis-Dekrete. Untersuchungen über zwei Synodaldekrete aus der Zeit Ptolemaios V. und ihre geschichtliche und religiöse Bedeutung. Bd. I–II. (Ägyptologische Abhandlungen, 73). Wiesbaden.

- 31. Shalaby, N. 2014: An offering table of a Prophet of Onuris from Abydos Cairo, Egyptian Museum JE 41438 (TR 23/1/15/7). Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 114, 447–454.

- 32. Smith, M. 2006: Osiris NN or Osiris of NN? In: B. Backes, I. Munro, S. Stöhr (Hrsg.), Totenbuch-Forschungen: Gesammelte Beiträge des 2. In-ternationalen Totenbuch-Symposiums, Bonn, 25. bis 29. September 2005. (Studien zum Altägyptischen Totenbuch, 11). Wiesbaden, 325–337.

- 33. Smith, M. 2012: New references to the deceased as Wsỉr n NN from the Third Intermediate Period and the earliest reference to a deceased wom-an as Ḥ.t-Ḥr NN. Revue d’Égyptologie 63, 187–196.

- 34. Taylor, J.H., Strudwick, N.C. 2005: Mummies: Death and the Afterlife in Ancient Egypt. Treasures from The British Museum. London.

- 35. Veïsse, A.-E. 2004: Les « révoltes égyptiennes » : recherches sur les troubles intérieurs en Égypte du règne de Ptolémée III à la conquête romaine. (Studia Hellenistica, 41). Leuven–Paris–Dudley (MA).