- PII

- S032103910015603-6-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S032103910015603-6

- Publication type

- Article

- Status

- Published

- Authors

- Volume/ Edition

- Volume 81 / Issue 2

- Pages

- 588-603

- Abstract

he article discusses four graves of the Maeotian burial ground “Prikubansky” (burials nos. 186, 253, 262, 384) dating from the first half of the fourth century B.C. Their funeral equipment, along with local handmade and wheelmade pottery, included red-figure skyphoi of the “fluent” style (F.B. Group), amphorae of different production centers, several black-glazed vessels. Cross-dating of various categories of imports has narrowed the chronology of tableware and ceramic containers.

- Keywords

- Prikubansky burial ground, Maeotian culture, import, amphorae, red-figure skyphoi, black-glazed pottery

- Date of publication

- 28.06.2021

- Year of publication

- 2021

- Number of purchasers

- 11

- Views

- 204

In 1998–2001, in the course of rescue investigations of the Krasnodar archaeological expedition of the Kuban State University, a considerable area of a Maeotian necropolis was excavated near the khutor (farmstead) of Prikubansky (Krasnoarmeysky district of Krasnodar Terriroty), that is situated in the flood-plain part of the right bank of the Kuban River, in its lower reaches. Totally, during these four years, 429 burials have been excavated where several thousand items of burial inventory including Maeotian wheelmade pottery and handmade ceramics, jewellery, weapon, etc. were found. Also a large quantity of imported ceramic ware was uncovered. A monographic publication of all the finds is expected in the nearest future, but in the present article, we wish to publish a small block of four complexes (burials nos. 186, 253, 262, and 384) which comprise a set of Attic red-figure skyphoi and amphorae from different production centers. Cross-dates of these categories of pottery considerably supplement our notions of the import dynamics of Greek products to the Maeotian milieu. Analysis demonstrates that Attic red-figured skyphoi were brought to the Maeotians of the Kuban region during a brief period within the first half of the 4th century B.C.

In the burials mentioned, four red-figure skyphoi of the Attic type (type A) with painting in a ‘fluent’ style have been uncovered. In its style, the painting of these vessels is comparable to the latest group of the Attic red-figure ware (‘Fat Boy Group’ or the F.B. Group after J.D. Beazley). Fragments with details of a painting of this type and a single archaeologically complete skyphos of this group from the Athenian Agora are dated to the second – third quarters of the 4th century B.C.1 These skyphoi belong to the number of the vessels which were copiously distributed throughout the world of the Classic period until the mid-4th century B.C.2

All the skyphoi here considered are produced from light-brown clay without discernible admixtures suggesting their Attic origin. In terms of their shape they have walls sagged near the bottom and an outturned pointed rim. The handles are of round section and trapezoid in the plan, slightly raised. The foot is rounded with a raised edge. The red-figure painting in the ‘fluent’ style, rather carelessly applied, is similar on all these items in its subject and manner of representations: palmettes beneath the handles, and volutes at the sides of the handles. Between the handles, paired figures are represented of young men draped in himation standing opposite each other with muffled hands. The glaze covers the inner and near-bottom parts of the vessels as well as the handles. The glaze is black with brown spots.

Totally, at the Maeotian sites on the right bank of the Kuban, now there are known 24 red-figure skyphoi in the ‘fluent’ style (including the fragmentary and reused bottom parts). Only 9 items among them are archaeologically complete forms. A complete skyphos in an excellent state of preservation found in burial 46 of kurgan 2 at the Sereginskaya necropolis in the trans-Kuban region is dated to the second quarter of the 4th century B.C.3 Generally, the period of the use of skyphoi with ‘fluent’ painting, as demonstrated by the complexes of the Prikubansky necropolis, is limited by the first – early third quarter of the 4th century B.C.4 This date corresponds well with the chronological situation with analogous ware in the Northern Black Sea littoral5 and on the Lower Don.6

4. Limberis, Marchenko 2015, 234–239.

5. Rogov, Tunkina 1998, 165; Maslennikov 2012, 70, 72, № 12, 13, Fig. 2, 4–5a; Vdovichenko et al. 2019, 49, № 290–326.

6. Brashinskiy 1980, 55.

For a more complete idea about the Maeotic complexes here considered, a brief description of the burials (in the chronological order) will be presented below while red-figure skyphoi, other black-glazed vessels and amphorae from different production centers encountered in association with them will be separately analysed.

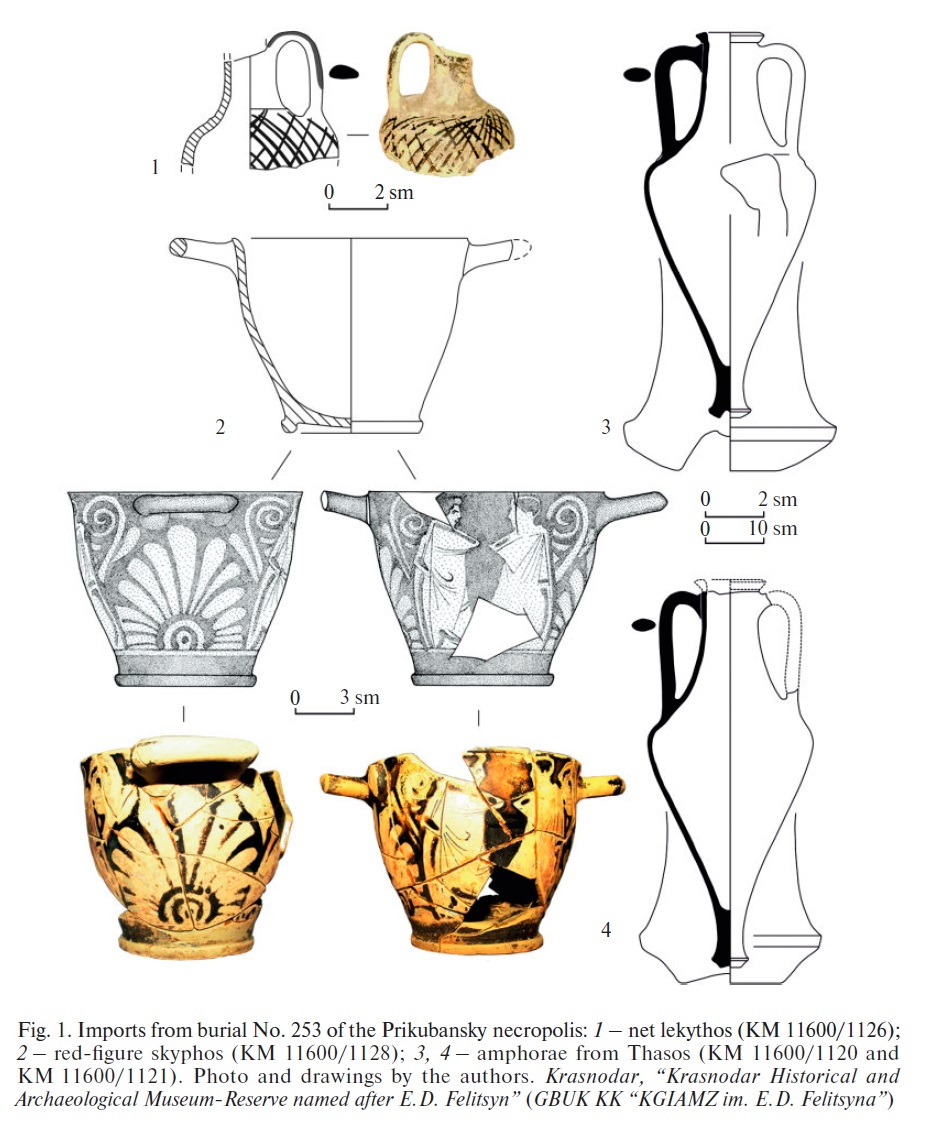

Burial No. 253

This burial was looted in antiquity, no human skeletal remains were here found.7 The grave goods: red-figure skyphos, two Thasian amphorae, mesh lekythos, handmade and grey-ware pottery, a bronze mirror and several small objects (spindle-whorl, beads, knife).

Of four skyphoi, the vessel from burial No. 253 (Fig. 1, 2) is distinguished in its squatter shape (with slightly tapering lower body) and, according to the standards of the Athenian Agora, it is datable to a slightly earlier time than the ware from other burials, i.e. to a range within 400–375 B.C.,8 as already noted before.9 As to the painting, on this vessel also the figures of two youths in himation facing each other are depicted. A similar in its style fragment of a skyphos from the Athenian Agora is dated to the beginning of the 4th century B.C.10 Therefore, the skyphos from burial No. 253 can be perhaps considered as belonging to a group preceding that of ‘Fat Boy’ (F.B. Group).

9. Limberis, Marchenko 2010, 323; 2015, 237.

10. Moore 1997, 304, no. 1294.

The same burial yielded a lekythos with mash ornament (Fig. 1, 1) of which only the upper body is preserved; however it is obvious that this toilet vessel belongs to the Boulas Group.11 The beginning of the manufacture of such lekythoi in the Mediterranean region is dated to the first quarter of the 4th century B.C., while their mass production and wide use in the funerary rite falls on the second – third quarters of that century.12 This date coincides with the period of the regular burying of such lekythoi at necropoleses of the Northern Black Sea Region.13 Mash lekythoi are fairly rare finds at Maeotian burial grounds. Thus three complete examples were found in the Maryanskaya (Maryinskaya) kurgan,14 and yet another one was retrieved from the ritual complex of the Tenginskaya necropolis in the Transkuban region.15 Several fragmentary examples come from the cemetery of Lebedi III.16 They all belong to different issues and are widely dated to the first half of the 4th century B.C. As to the lekythos from burial No. 253, it seems to have belonged to one of the earliest series and, probably, its date can be placed to within the boundaries of the first quarter of the 4th century B.C. At least, a lekythos with exactly the same carefully executed ‘checked’ design over the body and with vertical white spots and bands on the throat comes from burial M.04 at the necropolis of Panskoye I, where it was neighboring an amphora of the Murighiol type of the beginning of the 4th century B.C.17

12. Robinson 1950, 148–150, 160–162, pl. 105–108.

13. Rogov, Tunkina 1998, 173–174; Rogov 2011, 120–121.

14. Reports of the Imperial Archaeological Commission (ОАК) in 1912, 54 Fig. 73, above, in the center; Monakhov et al. 2019, 61, Fig. 46.

15. Erlikh 2011, 26, 50, Fig. 68, 5.

16. Limberis, Marchenko 2016а, 67–68.

17. Monakhov, Rogov 1990, 127–128, Pl. 4; Rogov, Tunkina 1998, 173, Fig. 7, № 19; Monakhov 2003, 80, Pl. 55, 4.

Practically identical Thasian amphorae from burial No. 253 (Pl. 1), one with the rim and handle lost (Fig. 1, 3, 4), belong to the ‘early biconical’ series (II-B-1). Stamps on the handles or throats are absent inducing us to search for analogues among some reliably dated complexes.

The closest of these parallels include an amphora from the ‘Yuzhny’ kurgan excavated in 1913 near the stanitsa of Yelizavetinskaya on Kuban, found together with a Heraklean amphora with a stamp of the early fabricant Aristippos,18 as well as two similar unstamped Thasian amphorae from the Dvugorbaya Mogila kurgan in the Azov Sea region where they were uncovered in association with Heraklean amphorae with stamps of early fabricants Archelas and Eukleiōn.19 In both cases, the vessels are dated to the very beginning of the 4th century B.C. In addition, there are similar Thasian amphorae with stamps of early magistrates Kuros and Saturos, in the first case from burial No. 254 of the Prikubansky necropolis and, in the second, from room No. 32 in Gorgippia, which, in turn, are well synchronized within the 390s B.C.20 In our case, amphorae from burial No. 253 are well correlated with the date of the skyphos from this burial which is datable to within the 390s – early 380s B.C.

19. Monakhov 1999, 162–163, Pl. 55.

20. Monakhov 1999, 234, Pl. 96; 2003, 66–67, Pl. 42, 4, 5; Kats 2015, cat. 32.

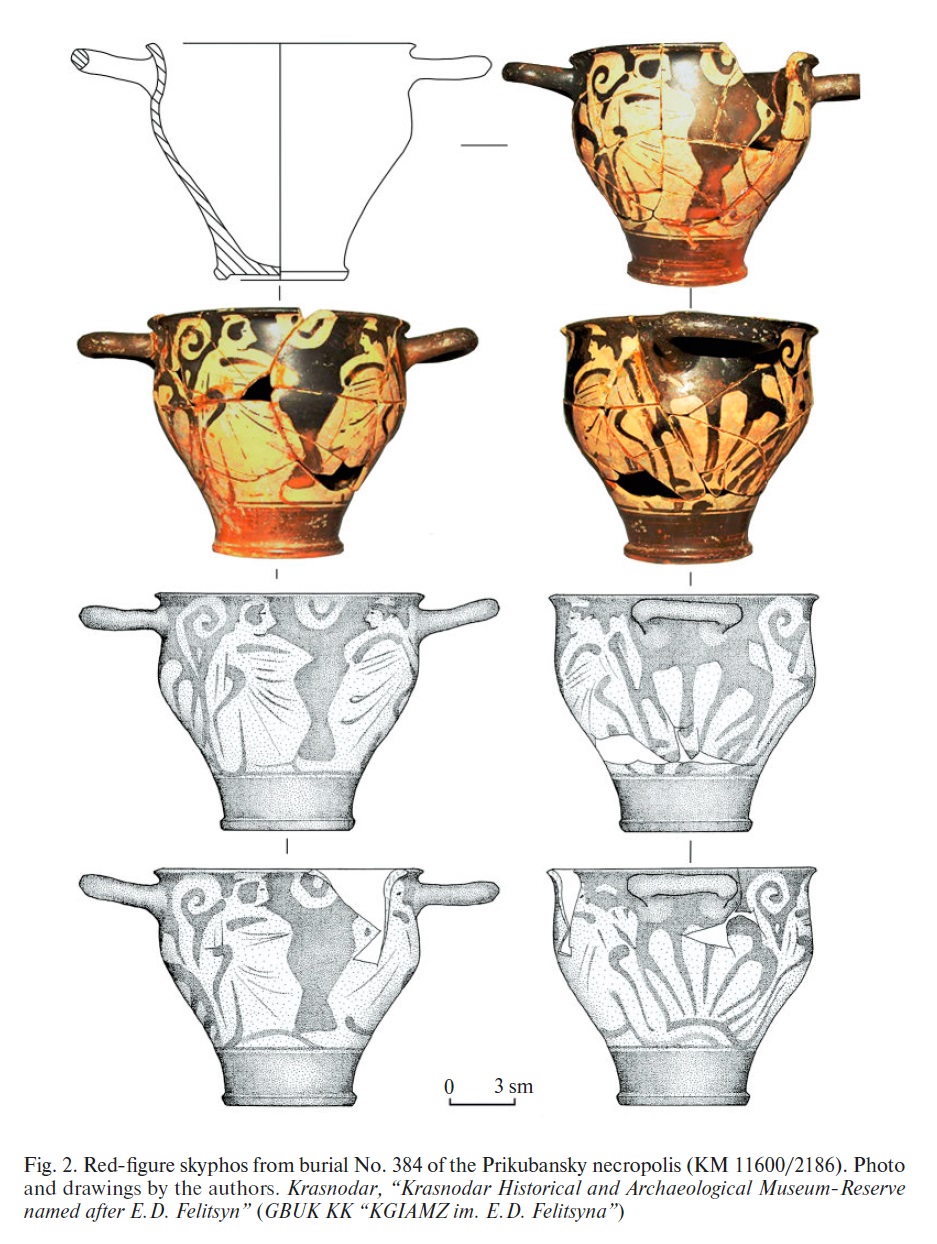

Burial No. 384

Grave No. 384 was a burial of a male (?) aged 45–50 years old and interred with numerous grave goods: a red-figure skyphos, amphorae from Mende and from an unidentified production center, grey-ware and handmade vessels of the Maeotian production, ornaments, and various small objects.

The red-figure skyphos from this burial has a slightly uncommon profile – its height is somewhat greater retaining the diameter of the rim with the decrease of the diameter of the foot (Pl. 2); the walls near the bottom are distinctly compressed. Forms of black-glazed skyphoi of a similar type are common for the second quarter of the 4th century B.C.21 The manner of the painting also somewhat differs: a band of black glaze on the lower body is broader than that of the example from burial No. 253; on both sides, figures of youths in himation are depicted standing at some distance and facing each other. Between them, at the level of the face, a round object, possibly a tympanum, is represented (Fig. 2).

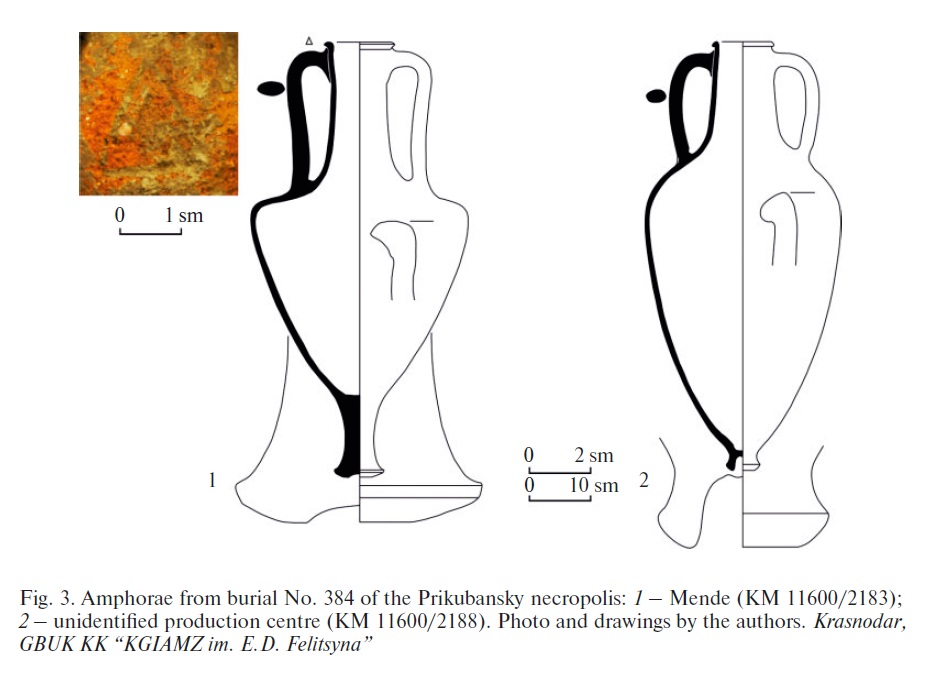

The first amphora (Fig. 3, 1) from this burial is a product of Mende of the ‘Porticello’ variant (II-B) and has a wedge-shaped rim separated by a slight cut from below, a high neck narrowing beneath the upper attachment of the handles, a smooth transition toward the broad and almost horizontal shoulder, the body of almost conical shape, and widened profiled foot with a hemispherical hollow. On the handle, there is a relief stamp in the form of the letter “Δ” in a triangular frame. Amphorae of this type are numerously recorded in a series of representative complexes, in particular in the eponimic Porticello Shipwreck, in kurgans No. 2 and at the Yelizavetovskoye necropolis (of 1909), kurgan No. 28 at the cemetery of ‘Plavni’, in the Chersonesean well of 1992, in room No. 32 in Gorgippia, etc.22 Through Heraklean and Thasian stamps in these complexes, they are reliably datable to the first two decades of the 4th century B.C. Such Mendean amphorae were retrieved from two other burials of the Prikubansky necropolis (No. 32 and No. 157); moreover, in the first of the latter, a Heraklean amphora with a stamp of the early fabricant Dionysios was found together with the amphora from Mende. The amphora from burial No. 157 mentioned above is practically identical to the one under consideration; moreover, it was found accompanying a vessel of the next ‘Melitopol’ variant dating the amphora from burial No. 384 to within the 370s – early 360s B.C.

The second amphora from burial No. 384 is from an unidentified center of production (Fig. 3, 2). By the present day it finds no parallels. It has a small beak-shaped rim, a high neck flaring downward, an ovoid body and a rather low carinated foot with a deep trapezoid hollow. The clay is dark brown on the outside with numerous black inclusions and large quantity of mica and red on the inside. Similar clay is occasionally found in Thasian vessels, however the common morphological features do not allow us to attribute the given example to products of Thasian workshops. On the basis of the date of the Mendean amphora and the skyphos from this burial, this vessel (as also burial No. 384 itself) is datable to the beginning of the second quarter of the 4th century B.C.23

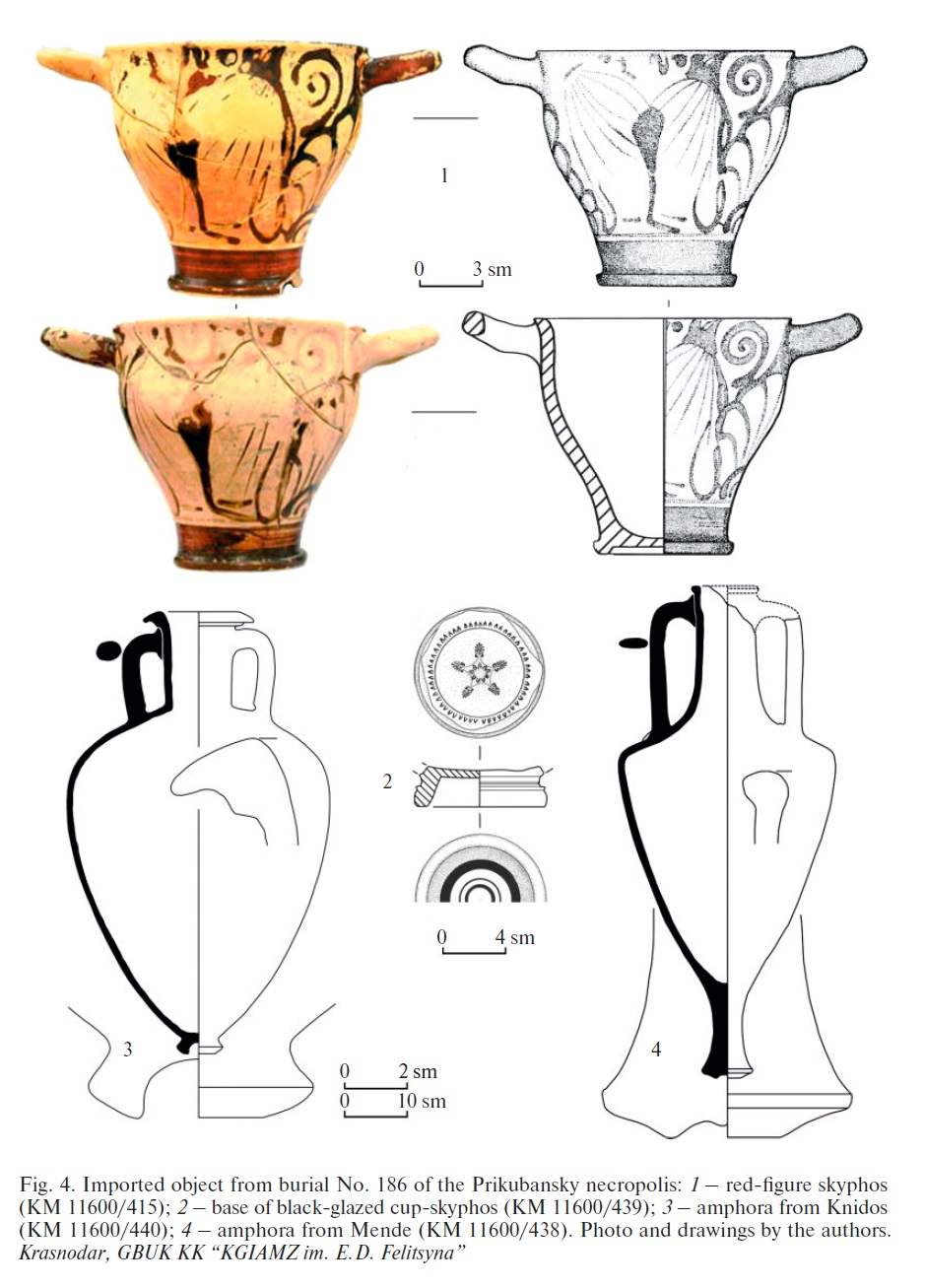

Burial No. 186

It was a burial of a man (?) in a wooden coffin. Grave goods: a red-figure skyphos, amphorae from Mende and Knidos, the base of a black-glazed skyphos, a yellow-ware mortar, a bronze cup, handmade and wheelmade grey-ware vessels (including a fish-plate and an askos), a spindle-whorl, a knife with a bone grip, a fragment of a mask-bead, a pebble, different jewelry and a bronze mirror.

The form of the red-figure skyphos is similar to the previously described one. The theme of the painting is the same: depiction of two youths in himation facing each other, between their heads a tympanum is placed (Fig. 4, 1). The manner of depiction is however more careful; the figures touch each other with elbows.

In addition, this burial yielded the foot of a cup-skyphos (Fig. 4, 2) reused as a small cup or a saltcellar. It is a very typical case for the Maeotian world. Only at the Prikubansky necropolis, five foots of vessels of this kind are known.24 The presence of a decoration combining stamped and carved elements on the inside of the bottom of this foot suggests its date as the beginning of the 4th century B.C.25

25. Sparkes, Talcott 1970, 112, no. 618.

The first amphora from burial No. 186 is of Knidian production; it has a mushroom-shaped outturned rim, a relatively low neck slightly tapering downward (funnel-shaped) with a distinct transition to the shoulder. The body is pythoid, the foot is broad carinated with a deep hemispherical hollow. The clay is light brown, soft and dense, containing sparse shell inclusions. Amphorae of this type some time ago were attributed as an independent ‘Yelizavetovskoye’ variant of Knidian containers (Fig. 4, 3).26

There are numerous analogues to them. First, a similar amphora comes from the central burial of kurgan No. 5 of the ‘Five Brothers’ group of the Yelizavetovskoye necropolis, whereas at the ritual deposit related with this burial, there were found three Heraklean amphorae with stamps of early fabricants Euridamos and Dionysios 1, as well as still a stray amphora (also from Heraklea) with the stamp of the early fabricant Kromnios.27 These facts provide us with a chronological link with the late 380 – early 370s B.C.

Quite a number of analogous Knidian jars come from several burials of the same Prikubansky necropolis. Thus in burial No. 159, an amphora of this type was encountered together with a biconical Thasian one and a Sinopean amphora (type I-A), which, according to all their analogues, are datable to within the end of the first – beginning of the second quarter of the 4th century B.C.28 Moreover, the Thasian amphora bears the stamp Ἀριστείδ(ης) | Θασ|ι Ἀριστα(γόρης),29 belonging to the magistrate Aristidos who was active in the 350s B.C.30 In burial No. 202 of the Prikubansky necropolis, a Knidian amphora of this type was found together with another large amphora with a mushroom-shaped rim from an unidentified production center.31 In burial No. 224 of the same necropolis, the Knidian amphora of the ‘Yelizavetovskoye’ variant was associated with a Thasian unstamped amphora of the ‘developed’ biconical series and an Attic black-glazed bolsal.32 Similar bolsals were distributed particularly in the second half of the 5th century B.C.; in the next century, they began to loose their popularity because of the appearance of kantharoi, but their manufacture continued until the late 4th century B.C.33 The closest analogue among the materials of the Athenian Agora is dated to the 380–350 B.C., but its handles are raised upward as is characteristic of the younger pottery.34 The bolsal from burial No. 224 is probably dating from the beginning of the second quarter, while the dates of the amphorae from the burial do not exceed the middle of the century.

29. Reading by A.B. Kolesnikov.

30. Kats 2007, 415, Supplement II.

31. Limberis, Marchenko 2018, 101, Fig. 4.

32. Limberis, Marchenko 2018, 101, Fig. 5.

33. Sparkes, Talcott, 1970, 108.

34. Sparkes, Talcott, 1970, 108, no. 558.

Finally, burial No. 294з of the necropolis of Starokorsunskoye settlement No. 2, yielded together with a Knidian amphora of the same Yelizavetovskoye variant yet another Knidian amphora of the Cherednikovy variant, as well as a black-glazed skyphos and a black-glazed kantharos of the second quarter of this century.35

Thus the entire circle of reliably dated parallels indicates the second quarter of the 4th century for the Knidian amphora of the ‘Yelizavetovskoye’ variant from burial No. 186.

The second amphora from the burial belongs to the Mendean production of the ‘Melitopol’ variant (Fig. 4, 4). As it was supposed before, this variant is a rather late one but the finds from burial No. 157 of the Prikubansky necropolis of at once two amphorae of the ‘Porticello’ and ‘Melitopol’ types suggest that for some time they were manufactured simultaneously. Nevertheless, considering a series of representative complexes with ‘Melitopol’ amphorae (kurgan No. 1 near the village of Olgino, kurgan No. 4s near v. Petukhovka, kurgan No. 14 near v. Gyunovka, kurgan No. 16 near v. Verkhny Rogachik36) it seems that the amphora from burial No. 186 should be dated to within the second quarter of the 4th century B.C.

Taking in account the dates of all the categories of imports, the chronology of burial 186 may be placed within the second quarter of the 4th century BC.

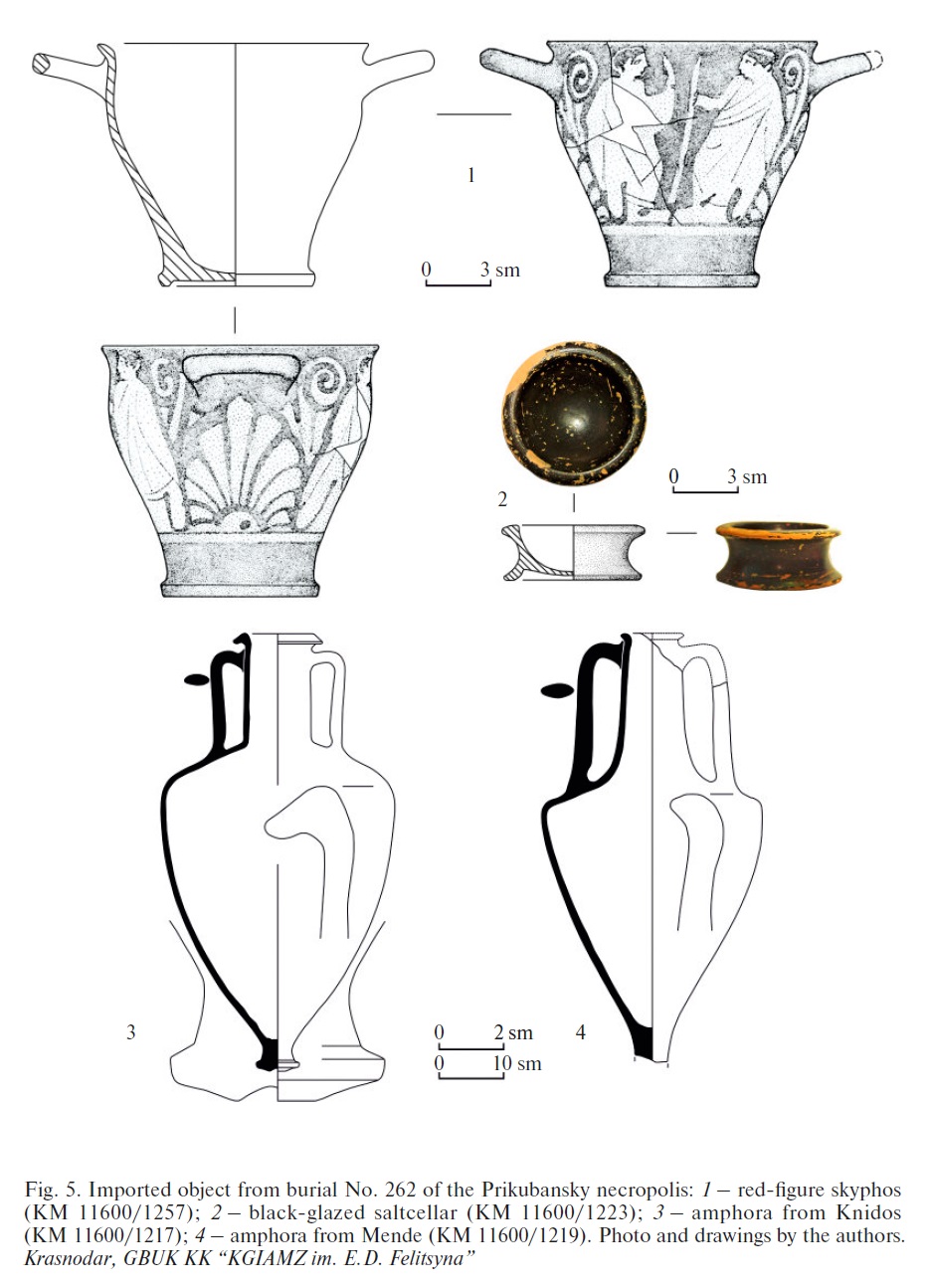

Burial No. 262

It was the grave of a female (?) 30–40 years old and contained a fairly diverse funerary inventory: a red-figure skyphos, amphorae from Knidos and Mende, a black-glazed saltcellar, Maeotian handmade and grey-ware pottery, diverse jewerly and numerous small objects.

The red-figure skyphos is morphologically identical to the previous one from burial No. 186 (Pl. 2). On its both sides, there are representations of two youths in himation facing each other: one with a staff in the right hand, the other – with a strigil in the left (Fig. 5, 1).

The saltcellar with a concave wall belongs to the variant with a recessed underside resembling a pushed-in ring base. This form of saltcellars appeared in Attica in the second half of the 5th century B.C. and became most popular in the second and third quarters of the 4th century B.C. About 315 B.C., their manufacture ceased in Attica.37 Some researchers supposed that the importation of such saltcellars to the Northern Black Sea region had ended before the mid-4th century B.C.,38 however analysis of the mass finds from Northwestern Crimea and the Crimean Azov littoral has demonstrated that their main quantity comes from the cultural layers of the third quarter of the 4th century B.C.39 Saltcellars of this type were found also in burials nos. 230 and 346 of the second quarter of the 4th century BC at the Prikubansky necropolis.40 In addition, they are known among the ceramic complexes of the Maryanskaya41 and Yelizavetinskaya No. № 7/191742 barrows. An example of the second quarter of the 4th century B.C. is the closest parallel among the materials from the Athenian Agora.43 These facts entirely correspond to the dating of the skyphos from burial No. 262.

38. Rogov, Tunkina 1998, 171.

39. Egorova 2009, 38, № 359–371; Maslennikov 2012, 180, 182.

40. Limberis, Marchenko 2010, 335, № 37–39; 2017, 208, № 1–3.

41. ОАК for 1912, 54 Fig. 73, top right; Monakhov et al. 2019, 61, Fig. 46.

42. Galanina 2009, 89, Fig. 4.

43. Sparkes, Talcott 1970, 137–138, nо. 936.

The Knidian amphora from burial No. 262, in terms of its morphological parameters (Pl. 1), belongs to the type with a ‘high neck and mushroom-shaped rim’, although not to the Yelizavetovskoye but to the ‘Gelendzhik’ or ‘Cherednikov’ variant (I-B or I-D) with flattened shoulders, less massive mushroom-shaped rims and a differing, very uncommon, profile of the feet (Fig. 5, 3). The distinguishing of the Gelendzhik variant presently seems not much reliable and moreover only its single examples are now known. Only a single amphora of this variant has been encountered in the complex of burial No. 13 at the necropolis of settlement No. 2 near the Lenin khutor (farmstead),44 and moreover in the association with an amphora produced in Erythrai. The latter has not been included in the summary of amphorae from Erythrai but, evidently, it has a number of parallels among the examples of arbitrary type III dated extremely widely to the middle or, perhaps, the third quarter of the 4th century B.C.45 The closest analogues come from burial No. 652з of the necropolis of the Starokorsunskoye settlement No. 2 where two similar vessels were found, as well as a fragmentary amphora from Peparethos and black-glazed ware generally dated to the second quarter of the 4th century B.C.46 The abovementioned amphora from burial No. 294з of the necropolis of the Starokorsunskoye settlement No. 2 is of greater height and slightly lesser diameter.

45. Monakhov 2013, 40–41, Pl. V.

46. Limberis, Marchenko 2016b, 80, Fig. 3.

From the above, it follows that the amphora from burial No. 262 can be dated to the second quarter of the 4th century B.C.

Amphora from Mende (Fig. 5, 4) is similar to the vessel from burial No. 186 described above and also is datable to within the second quarter of the 4th century B.C.

Generally, the burials with amphorae and red-figure skyphoi in the ‘fluent’ style are datable to within a fairly limited range of the 380–350s B.C. Comparison of the dates of these two categories of grave goods, along with a consideration of known analogues of the little numerous other imports has allowed us to obtain slightly more narrow dates than those defined earlier, to describe in more details the chronology of the skyphoi and to date the complexes in general. In turn, this enables us to define more precisely the time of the manufacture and use of different objects of Maeotian production, mainly pottery.

Table 1

Metric parameters of amphorae from the Prikubansky necropolis47

| Burial No. | Production center | Linear dimensions, mm | Date, BC | Fig. | |||||

| Н | Н0 | Н1 | Н3 | D | d1 | ||||

| 253 | Thasos | 660 | 572 | 260 | 155 | 290 | 115 | 390s | 1, 4 |

| 253 | Thasos | - | 567 | 281 | 187 | 280 | - | 1, 3 | |

| 384 | Mende | 710 | 576 | 290 | 213 | 358 | 116 | 370s – early 360s | 3, 1 |

| 384 | Unidentified center | 700 | 668 | 300 | 160 | 315 | 100 | 370-е – early 360s | 3, 2 |

| 186 | Knidos | 706 | 675 | 310 | 150 | 420 | 176 | Second quarter of the 4th cen. | 4, 3 |

| 186 | Mende | 786 | 635 | 290 | 202 | 344 | 110 | Second quarter of the 4th cen. | 4, 4 |

| 262 | Knidos | 678 | 630 | 270 | 170 | 366 | 140 | Second quarter of the 4th cen. | 5, 3 |

| 262 | Mende | - | 612 | 280 | 209 | 340 | 96 | Second quarter of the 4th cen. | 5, 4 |

Table 2

Metric parameters of skyphoi from the Prikubansky necropolis

| Burial No. | Manufacturing center | Linear dimensions, mm | Date, BC | Fig. | ||

| Н | d of throat | d of base | ||||

| 253 | Attica | 100 | 121 | 73 | 390s – early 380s | 1, 2 |

| 384 | Attica | 109 | 123 | 61 | 370s – early 360s | 2 |

| 186 | Attica | 113 | 122 | 67 | Second quarter of the 4th cen. | 4, 1 |

| 262 | Attica | 113 | 126 | 73 | Second quarter of the 4th cen. | 5, 1 |

H – height; H0 – depth; H1 – height of the upper part; H3 – height of a throat; D – trunk diameter; d1 – diameter of the crown

References

- 1. Brashinskiy, I.B. (1980). Grecheskiy keramicheskiy import na Nizhnem Donu v V–III vv. do n.e. [Greek Ceramic Imports on the Lower Don in the 5th-3rd cent. B.C.]. Leningrad.

- 2. Yegorova, T.V. (2009). Chernolakovaya keramika IV–II vv. do n.e. s pamyatnikov Severo-Zapadnogo Kryma [Black-Glazed Pottery of the 4th-2nd cent. B.C. from the Northwestern Crimea Settlements]. Moscow.

- 3. Erlikh, V.R. (2011). Svyatilishcha nekropolya II Tenginskogo gorodishcha (IV v. do n.e.) [The Sanctuaries of the Necropolis II Tenginsky Settlement (4th cent. B.C.)]. Moscow.

- 4. Galanina, L.K. (2009). Kontakty Prikubanya s antichnym importom (po materialam Yelizavetinskikh kurganov) [Contacts of Prikuban Region with the ancient world (based on the materials of the Yulizavethian burial mounds)]. In: Epokha rannego zheleza. Sbornik nauchnykh trudov k 60-letiyu S.A. Skorogo, doktora arkhiologiyi. Kiev–Poltava, 86-90.

- 5. Ivanov, T. (1963). Antichna keramika ot nekropolya na Apoloniya [Ancient pottery from necropolis of Apollonia]. In: Apoloniya, Razkopkite v nekropole na Apoloniya prez 1947–1949 [Appolonia. Excavations of the Necropolis of Apollonia in 1947-1949]. Sofia, 65-273.

- 6. Kats, V.I. (2007). Grecheskiye keramicheskiye kleyma epokhi klassiki i ellinizma (opyt kompleksnogo izucheniya) [Greek Ceramic Stamps of the Classical and Hellenistic Epoch (Complex Research Result)]. Krymskoye otdeleniye Instituta vostokovedeniya NANU, Tsentr arkheologicheskikh issledovaniy “Demetra”. Simferopol–Kerch.

- 7. Kats, V.I. (2015). Keramicheskiye kleyma Aziatskogo Bospora. Gorgippiya i ee khora, Semibratneye gorodishche. Katalog. [Ceramic Stamps of Asiatic Bosporus. Gorgippia and Its Chora, Semibratneye Settlement. Catalogue]. Izdatel’stvo Saratovskogo universiteta. Saratov.

- 8. Leskov, A.M., Lapushnian, V.L. (eds.) (1987). Shedevry drevnego iskusstva Kubani. Katalog vystavki [Art Treasures of Ancient Kuban. Catalogue of Exhibion]. Moscow.

- 9. Limberis, N.Yu., Marchenko, I.I. (1997). Pogrebeniya s gerakleiskimi amphorami iz raskopok mogil’nika Starokorsunskogo gorodishcha № 2. In: M.Yu. Vakhtina, Yu.A. Vinogradov (eds.), Stratum Plus. Peterburgskiy arkheologicheskiy vestnik. Saint Petersburg–Chișinău, 81-93.

- 10. Limberis, N.Yu., Marchenko, I.I. (2010). Raspisniye i chernolakoviye sosudy iz Prikubanskogo mogil’nika (atributsiya i khronologiya) [Painted and black-glazed pottery from the cemetery of Prikubanskiy]. Drevnosti Bospora [Antiquities of Bosporus] 14, 322-356.

- 11. Limberis, N.Yu., Marchenko, I.I. (2015). Chernolakoviye skiphosy iz meotskikh pamyatnikov pravoberezh’ya Kubani [Black-glazed skythos from Meotian settlements of the right bank of the Kuban River]. Drevnosti Bospora [Antiquities of Bosporus] 19, 227-255.

- 12. Limberis, N.Yu., Marchenko, I.I. (2016a). Lekiphÿ v pogrebal’nom obryade meotov Pravoberezh’ya Kubani [Lekythos in burial rituals of meots on the right bank of the Kuban River]. In: Aziatskiy Bospor i Prikubanye v dorimskoye vremya [Asian Bosporus and Kuban Region in Pre-Roman Time]. Moscow, 64-70.

- 13. Limberis, N.Yu., Marchenko, I.I. (2016b). Pogrebeniye so steklyannoy chashkoy iz mogil’nika Starokorsunskogo gorodishcha № 2 [A burial with a glasscup from the cemetery of Stary-Korsun city-site no. 2]. Arkheologicheskiye vesti [Archaeological News] 22, 76-85.

- 14. Limberis, N.Yu., Marchenko, I.I. (2017). Miniaturniye chernolakoviye sosudy dlya servirovki stola iz meotskikh mogil’nikov pravoberezhya Kubani [Small black-glazed vessels for food service from Meotian burial grouns at the right bank of the Kuban River]. Antichniy mir i arkheologiya [Ancient World and Archaeology] 18, 206=223.

- 15. Limberis, N.Yu., Marchenko, I.I. (2018). Khonologiya pogrebeniyi s konskoy upryazhyu v zverinom stile iz Prikubanskogo mogil’nika [Chronology of the burials with animal-style horse harness from the Prikubansky burial ground]. Vestnik Volgogradskogo gosudarstvennogo universiteta. Seriya 4, Istoriya. Regionovedeniye. Mezhdunarodniye otnosheniya 23(3), 99-133.

- 16. Maslennikov, A.A. (2012). Raspisnaya keramika s pamyatnikov “tzarskoy” khory Priazovya [Painted ceramics from the monuments of „khory Priazoya”]. In: A.A. Maslennikov, Tzarskaya khora Bospora (po materialam raskopok v Krÿmskom Priazov’e). T. 2. Individual’niye nakhodki i massoviy arkheologicheskiy material [Individual finds and mass archaeological material]. Moscow.

- 17. Monakhov, S.Yu. (1999). Grecheskiye amfory v Prichernomorye: kompleksy keramicheskoy tary VII–II vv. do n.e. [Creek Amphorae in Black Sea area: Complexes of ceramic containers of the 7th-2nd cent. B.C.]. izdatel’stvo Saratovskogo universiteta. Saratov

- 18. Monakhov, S.Yu. (2003). Grecheskiye amfory v Prichernomorye: tipologiya amfor vedushchikh tsentrov-éksporterov tovarov v keramicheskoy tare. Katalog-opredelitel’ [Greek Amphorae in Black Sea Area: The Typology of Amphorae of the Leading Centers-Exporters of Goods in Ceramic Containers. Catalogue]. izdatel’stvo “Kimmerida”, izdatel’stvo Saratovskogo universiteta. Moscow–Saratov.

- 19. Monakhov, S.Yu. (2013). Zametki po lokalizatsii keramicheskoï tarÿ. III. Amforÿ i amfornÿe kleïma maloaziïskikh Érifr [Notes on localiztion of ceramic pachage. III. Amphorae and amphorae trademarks of Asian Erifral]. Vestnik drevneï istorii 3, pp. 28-51.

- 20. Monakhov, S.Yu., Rogov, Ye.Ya. (1990). Keramicheskiye kompleksÿ nekropolya Panskoye I [The ceramic complexes of necropolis. Panskoye I]. iyAntichniy mir i arkheologiya [Ancient World and Archaeology] 8, 122-151.

- 21. Monakhov, S.Yu., Kuznetsova, Ye.V., Churekova, N.B. (2017). Amfory V–II vv. do n.e. iz sobraniya gosudarstvennogo istoriko-arkheologicheskogo muzeya-zapovednika ”Khersones Tavricheskiï‘. Katalog [Amphorae of the 5th-2nd cent. B.C. from the Collection of the State Museum-Preserve „Tauric Chersonese.” Catalogue]. Saratov.

- 22. Monakhov, S.Yu., Kuznetsova, Ye.V., Limberis, N.Yu., Marchenko, I.I. (2018). Redkiye formy amphor iz Prikubanskogo nekropolya [The rare forms of amphorae from the Prikubanskiy necropolis]. In: V.V. Mayko (ed.), Arkheologiya antichnogo i srednevekovogo goroda. Sevastopol–Kaliningrad, 163-170.

- 23. Monakhov, S.Yu., Kuznetsova, Ye.V., Chistov, D.Ye., Churekova, N.B. (2019). Antichnaya amfornaya kollektsiya Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha VI–II vv. do n.e. Katalog [The Ancient Amphorae Collection of the State Hermitage Museum 6th-2nd cent. B.C. Catalogue]. Saratov.

- 24. Moore, M.B. (1997). Attic Red-Figured and White-Ground Pottery. (The Athenian Agora, 30). Princeton (NJ).

- 25. Picazo, M. (1977). Las Cerámicas Áticas de Ullastret. Barcelona.

- 26. Rogov, Ye.Ya., Tunkina, I.V. (1998). Raspisnaya i chernolakovaya keramika iz nekropolya Panskoye I [Painted and black-glazed pottery from the necropolis Panskoye I]. Arkheologicheskiye vesti [Archaeological News] 5, 159-175.

- 27. Rogov, Ye.Ya. (2011). Nekropol’ Panskoye i v Severo-Zapadnom Krymu [Necropolic Panskoye I in the Northwestern Krimea]. Simferopol.

- 28. Robinson, D.M. (1950). Excavation at Olinthus. Pt. XIII. Vases Found in 1934 and 1938. (The Johns Hopkins University Studies in Archaeology, 38). Baltimore.

- 29. Sparkes, B.A., Talcott, L. (1970). Black and Plain Pottery of 6th–5th and 4th Centuries BC. Pt. I. Text. Pt. II. Indexes and Illustrations (The Athenian Agora, XII). Princeton (NJ).

- 30. Stoyanov, R.V., Erim-Ozdogan, A. (2014). Kollektsiya cherno- i krasnofigurnoï keramiki iz raskopok poseleniya Menekshe Chataï v Propontide [Collection of black-figured pottery from the excavations of the Menekse Çataği settlement in Propontis]. Zapiski Instituta istoriyi material’noy kul’tury [Transactions of the Institute for the History of Material Culture] 10, 166-179.

- 31. Trias de Arribas, G. (1967-1968). Ceramicas griegas de la Peninsula Iberica. Vol. I–II. (Publicaciones de Arqueologia Hispanica, II). Valencia.

- 32. Vdovichenko, I.I., Turova, N.P. (2006). Antichniye raspisniye vazy iz sobraniya Yaltinskogo istoriko-literaturnogo muzeya [Antique Painted Vases of the Yalta Museum of History and Literature Collection]. Simferopol–Kerch.

- 33. Vdovichenko, I.I., Ryzhov, S.G., Zhestkova, G.I. (2019). Antichnaya raspisnaya keramika Khersonesa Tavricheskogo. Iz raskopok S.G. Ryzhova v 1976-2011 godakh [Ancient Painted Pottery of Tauric Chersonesos. From the Excavations of S.G. Ryzhov in 1976-2011]. Sevastopol.

2. Ivanov 1963, 199–201, Pl. 106–108, № 485–488; Trias de Arribas 1967, I, 272, 298, 399, 506–507, lám. CLXIV, 1, 7; CLXVI, 13; CLXXXI, 1; CLXXXV, 5; CCLVI; CCLVII; Picazo 1977, 73, lám. XX; Stoyanov, Erim-Ozdogan 2014, 174–175, Fig. 3, 8а–8b, Cat. № 25.