- Код статьи

- S032103910015605-8-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S032103910015605-8

- Тип публикации

- Статья

- Статус публикации

- Опубликовано

- Авторы

- Том/ Выпуск

- Том 81 / Выпуск 2

- Страницы

- 604-633

- Аннотация

The article provides a publication and analysis of ten Egyptian terracotta figurines of Isis from the Graeco-Roman period (collection of the Department of Ancient Orient, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow). They come from the collections of V.S. Golenischev, N.G. Ter-Mikaelian and O.V. Kovtunovich and are dated to the broad period – from the early Hellenistic age (4th–3rd cent. B.C.), to the Late Ptolemaic (1st cent. B.C.) and Roman periods (1st–3rd cent. A.D.), giving evidence of the popularity of Isis’ cult in Graeco-Roman Egypt. The images of the goddess studied in this paper have additional attributes adopted from the female deities of the Greek (Aphrodite, Demeter, Selene) and eastern pantheons. These features allow considering the aspects of Isis’ image as a syncretic deity, embodying both the patroness of motherhood and female attractiveness.

- Ключевые слова

- Graeco-Roman Egypt, Egyptian terracottas, Isis, religious syncretism, ancient Egyptian religion, Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts

- Дата публикации

- 28.06.2021

- Год выхода

- 2021

- Всего подписок

- 11

- Всего просмотров

- 237

This publication describes ten Egyptian terracotta figurines of the goddess Isis from the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts: eight figurines come from the collection of V.S. Golenischev, one (I,1a 7924) was acquired from N.G. Ter-Mikaelyan in 1981, another one (I,1a 7973) was purchased in 1986 from O.V. Kovtunovich.

By the number of Egyptian terracottas in museum collections and private collections, the first place is taken by images of Harpocrates, then go Isis and servants and goddesses associated with her.1 Meanwhile, the widespread of Isis cult during Graeco-Roman Period in popular and official beliefs, not only in Egypt, but also beyond its borders, far exceeded the glory of Harpocrates. Isis becomes a ‘Myrionyme’ goddess2 assimilating the functions of many Egyptian and some Greek goddesses; she is also the goddess of the mysteries, which Apuleius eloquently testifies, in particular, in ‘Metamorphoses’, calling Isis ‘the deliverer of the human race’ (Apul. Met. XI. 25).

CATALOGUE

1. Statuette of Isis-Thermuthis (Fig. 1)

Inv. No. I,1a 2740 (ИГ 3079). From the collection of V.S. Golenischev (1911).

Date: Roman Period, the reign of the Severan dynasty.

Place of discovery: unknown; purchased in Egypt.

Preservation: intact, slight chipping at the left ear.

Dimensions: H. 27.2 cm; W. 12.0 cm; Th 5.6 cm.

Manufacturing method: impression in a double-sided mould; trimmed and smoothed connecting seams at sides; high quality impression of the front side, with excellent detailing; simple, smoothed back side, with a technological hole with a diameter of 1.3 cm.

Material: alluvial fine hard dark red-brown clay (2.5YR4/3), with large amount of mica, medium amount of limestone, small admixture of vegetal particles.

Outer surface treatment: none.

Firing: regular oxidizing.

Note: traces of milky white gypsum-like substance on the face.

Publications: Berlev et. al. 2002, cat. 670; Vassilieva 2013, cat. 8.

Analogies: Kaufmann 1913, 45, Abb. 26; Breccia 1934, pl. VIII, 28−30; Bayer Niemeier 1988, No. 230−233; Dunand 1990, No. 387; Fjeldhagen 1995, cat. 44–45; Bailey 2008, No. 3017−3019; cf. Weber 1914, Taf. 3, 30, cf. 33–34; Perdrizet 1921, pl. XV, 4; Ewigleben, Grumbkow 1991, Kat. 39.

2. Statuette of Isis nursing Apis (Fig. 2)

Inv. No.: I,1a 2902 (ИГ 3078). From the collection of V.S. Golenischev (1911).

Date: 2nd–3rd cent. A.D.

Place of discovery: unknown; purchased in Egypt.

Preservation: the lower part of the statuette at the back and the right corner of the pedestal lost; chips; traces of red paint and white coating; cracks; surface impurity.

Dimensions: H. 26.7 cm; W. 14.7 cm; Th. 7.0 cm.

Manufacturing method: impression in a double-sided mould; smoothed connecting seams at sides; medium quality impression of the front side, in places probably with additional detailing; the back is flat and smoothed, with a technological hole of 1.6 cm diameter.

Material: alluvial medium-fine hard red-brown clay (2.5YR4/3, exterior surface 5YR5/4 in places), with significant admixture of mica, medium amount of limestone and vegetal particles, small amount of white particles (crushed river shells?).

Outer surface treatment: none.

Firing: regular oxidizing.

Note: traces of white gypsum-like substance on the face, sometimes covered over with red ochre.

Publications: Berlev et. al. 2002, cat. 677; Vassilieva 2013, cat. 9.

Analogies: Breccia 1934, pl. X, 37; Dunand 1979, No. 17/18; Ewigleben, Grumbkow 1991, Kat. 34; Fjeldhagen 1995, cat. 39; Török 1995, pl. LVI, 106; Ashton 2003, 86 (UC 33564); Boutantin 2006, 320, fig. 3.

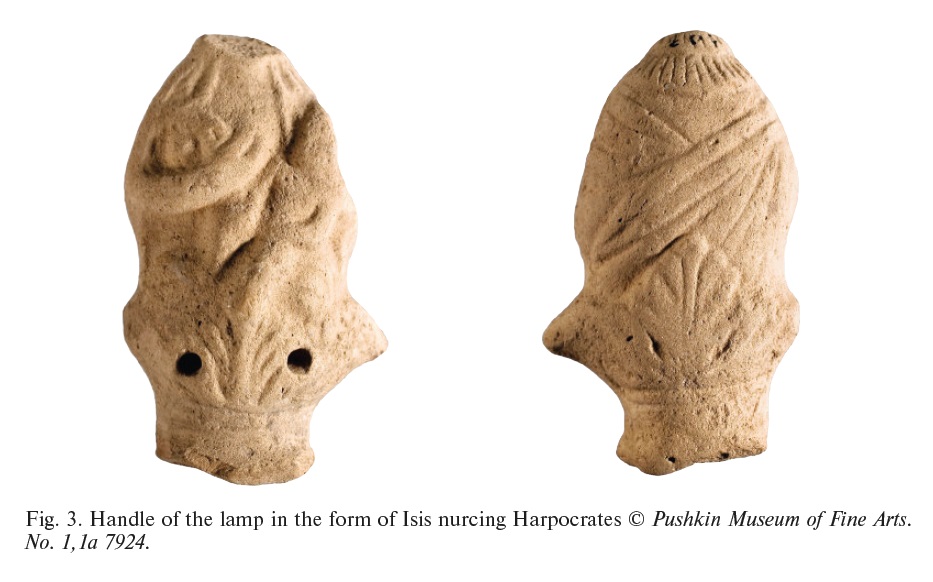

3. Handle of the lamp in the form of Isis nursing Harpocrates (Fig. 3)

Inv. No.: I,1a 7924 (КП 358058). From the collection of N.G. Ter-Mikaelyan (1981).

Date: 1st cent. B.C., Roman Period.

Place of discovery: unknown; purchased in Egypt.

Preservation: head, column trunk and body of the lamp lost; surface abrasions.

Dimensions: Н. 6.5 cm; W. 3.9 cm; Th. 2.9 cm.

Manufacturing method: impression in a double-sided mould; medium quality front impression; embossed back side, medium quality impression; with two technological holes with a diameter of 0.3 cm and 0.35 cm on the back side.

Material: marl fine medium-hard yellowish-beige clay (10YR7/4), average amount of white particles (crushed river shells?), small amounts of mica and vegetal particles.

Outer surface treatment: none.

Firing: regular oxidizing.

Publications: Berlev et. al. 2002, cat. 680; Vassilieva 2013, cat. 14.

Analogies: Weber 1914, Taf. 2, 19–20; Perdrizet 1921, pl. XVI, 2; Breccia 1926, tav. XXXVI, 7; Breccia 1934, II.1, pl. XXIV, 5–8, cf. pl. XLV, 8; Tran Tam Tinh 1973, pl. LX–LXIX; Dunand 1979, cat. 6, pl. VI; Bayer-Niemeier 1988, No. 28; Schürmann 1989, Taf. 170, Kat. 1023; Fjeldhagen 1995, cat. 36–37; Zych 2004, 83–84, fig. 5; Hussein 2016, 156–157, Taf. 10 (Kat.-NR.51a-b); Cf. Philipp 1972, Kat. 28.

4. Statuette of Isis-Demeter-Selene (Fig. 4)

Inv. No.: I,1а 2916 (ИГ 2966). From the collection of V.S. Golenischev (1911).

Date: second half of the 2nd – beginning of the 3rd cent. A.D.

Place of discovery: unknown; purchased in Egypt.

Preservation: intact; chips and heavily scuffed surfaces.

Dimensions: H. 19,2 cm, W. 9,6 cm, Th. 3,9 cm.

Manufacturing method: impression in a double-sided mould; trimmed and smoothed connecting seams at sides; high quality impression of the front side, medium quality impression of the embossed back side.

Material: alluvial fine hard brown clay (7.5YR4/3), with average amount of mica and crushed river shells, with a small amount of vegetal inclusions and a slight admixture of limestone.

Outer surface treatment: partially polished front and rear sides; further refined relief details on the front surface; images traced on the back surface (pruning on wet clay).

Firing: regular oxidizing.

Note: probably from the same workshop and pottery series with the lower part of statuette I, 1a 2920.

Publications: Berlev et. al. 2002, cat. 672; Vassilieva 2013, cat. 11.

Analogies: Schürmann 1989, Taf. 171, Kat. 1029; cf. Mollard-Besques 1963, pl. 32a, 34c, 36b, 37a-f; Philipp 1972, Kat. 35.

5. Statuette of Isis-Demeter-Selene (Fig. 5)

Inv. No.: I,1a 2920 (ИГ 2965). From the collection of V.S. Golenischev (1911).

Date: second half of the 2nd – early 3rd cent. A.D.

Place of discovery: unknown; purchased in Egypt.

Preservation: composed of two fragments; surface abrasions and impurity.

Dimensions: H. 19.0 cm, W. 9.7 cm, Th. 3.9 cm.

Manufacturing method: (head) impression in a double-sided mould; the connecting seams on the sides are trimmed and smoothed; good quality impression of the front side, medium quality impression of the back side; (body) impression in a double-sided mould; the connecting seams on the sides are trimmed and smoothed; high quality impression of the front side, medium quality impression of the embossed back side.

Material: (body) alluvial fine hard brown clay (7.5YR4/3), with average amount of mica, with small amounts of crushed river shells and vegetal inclusions; (head) clay visually close to body clay fabric (7.5YR4/3 for surface, 7.5YR5/4 for core).

Outer surface treatment: the head has no additional treatment; the body has additional treatment of solid moldings on the front surface (trimming on wet clay), the back surface is smoothed in some places, additional images were traced on wet clay.

Firing: regular oxidizing.

Note: late restoration: two different statuettes are pieced together (the head is of the ‘oranta’ statuette type, the torso is analogous to I, 1a 2916), the head and the body were connected by grayish white plasterlike substance; the lower part of the statuette is possibly from the same workshop and pottery series with I, 1a 2920.

Publications: Vassilieva 2013, cat. 12.

Analogies: (head) Breccia 1934, pl. LVII, 280; Eisenberg 2014, 37, No. 71; (body) Schürmann 1989, Taf. 171, Kat. 1029.

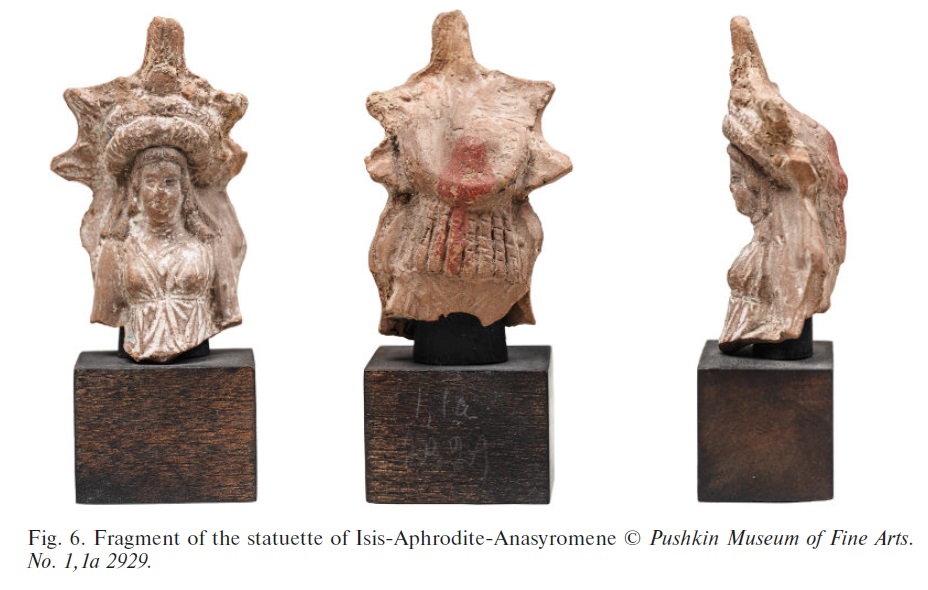

6. Fragment of the statuette of Isis-Aphrodite-Anasyromene (Fig. 6)

Inv. No.: I,1a 2929 (ИГ 3051). From the collection of V.S. Golenischev (1911).

Date: late 3rd cent. B.C.

Place of discovery: unknown; purchased in Egypt.

Preservation: the part of the statuette below the waist with the arms below the elbow were lost; the headdress is glued together; the paint layer is almost completely lost.

Dimensions: H. 7.1 cm, W. 4.0 cm, Th. 2.6 cm.

Manufacturing method: impression in a double-sided mould; the connective seams on the sides are trimmed and smoothed; good quality impression of the front side, medium quality impression of the embossed back side, a technological hole with a diameter of about 1 cm.

Material: alluvial fine hard pale brown clay (5YR5/2 and 5YR4/2), with average amount of mica, small amounts of white particles (crushed river shells?) and vegetal inclusions.

Outer surface treatment: none.

Firing: regular oxidizing.

Note: traces of pinkish-white gypsum-like substance and blue pigment on the front side; traces of red pigment on the back side.

Publications: Berlev et. al. 2002, cat. 676; Vassilieva 2013, cat. 3.

Analogies: Szymańska 2005, pl. V, cat. 46; cf. Ewigleben, Grumbkow 1991, Kat. 44; Szymańska 2000, 81, Fig. 3.

7. Fragment of the statuette of Isis-Aphrodite (Fig. 7)

Inv. No.: I,1a 2848 (ИГ 3089). From the collection of V.S. Golenischev (1911).

Date: Ptolemaic Period.

Place of discovery: unknown; purchased in Egypt.

Preservation: lost feet; deep chipping on the left arm; surface abrasions and impurity.

Dimensions: H. 19.9 cm, W. 6.2 cm, Th. 3.9 cm.

Manufacturing method: impression in a double-sided mould; the connecting seams are trimmed and carefully smoothed on the sides; good quality impression of the front side; good quality impression of the embossed back.

Material: alluvial fine hard dark red-brown clay (2.5YR4/4), with average amount of mica, small admixture of white particles (crushed river shells?) and vegetal inclusions.

Outer surface treatment: partly smoothed.

Firing: regular oxidizing.

Note: slight traces of white gypsum-like substance on the face.

Publications: Berlev et. al. 2002, cat. 673; Vassilieva 2013, cat. 1.

Analogies: Bayer-Niemeier 1988, Nr. 244; Dunand 1990, No. 328; cf. Weber 1914, Taf. 20, 201; Perdrizet 1921, pl. IV, 1; Szymańska 2005, pl. IV, cat. 28; Bailey 2008, No. 2995, 2997.

8. Statuette of Isis-Aphrodite (Fig. 8)

Inv. No.: I,1a 6889 (ИГ 3310). From the collection of V.S. Golenischev (1911).

Date: 1st cent. A.D.

Place of discovery: unknown; purchased in Egypt.

Preservation: glued together from several fragments; a part of the headdress, left hand, four fingers of the right foot lost; the surface of its nose and chest, leaves on shoulders partly broken; cracks; chipping.

Dimensions: H. 43.4 cm, W. 12.3 cm, Th. 6.2 cm.

Manufacturing method: impression in a double-sided mould; the connecting seams on the sides are trimmed and smoothed; high quality impression of the front side; good quality impression of the back; on the back of the head (behind the headdress) is a technological hole in the shape of an irregular oval 4.2 × 4.8 cm, the hole edges were trimmed.

Material: alluvial fine hard brown clay (5YR4/3), with small amounts of mica and vegetal particles, rare inclusions of limestone.

Outer surface treatment: the front side is smoothed and partially polished, the rear side is slightly polished.

Firing: regular oxidizing.

Note: slight traces of a yellowish-white gypsum-like substance on the obverse.

Publications: Pavlov, Hodjash 1985, 17, Table 21; Berlev et. al. 2002, cat. 668; Vassilieva 2013, cat. 2; Penna 2016, cat. 4.

Analogies: Weber 1914, Taf. 21, 200, 206; Breccia 1934, pl. IV, 10–11; Philipp 1972, Kat. 12, 18; Dunand 1990, No. 328−338; Ewigleben, Grumbkow 1991, Kat. 43; Fjeldhagen 1995, cat. 50−52; Bailey 2008, No. 3000.

9. Fragment of the statuette of Isis-Aphrodite (Fig. 9)

Inv. No.: I,1a 2803 (ИГ 3116). From the collection of V.S. Golenischev (1911).

Date: Roman Period.

Place of discovery: unknown; purchased in Egypt.

Preservation: the front part of the head is preserved; the upper part of the headdress and a fragment of curls from the left side and the body lost; on the face is a crack, on the right side; chipping, scratches.

Dimensions: H. 6.2 cm, W. 4.3 cm, Th. 2.3 cm.

Manufacturing method: impression in a double-sided mould; high quality impression of the front side.

Material: alluvial fine hard pale red-brown clay (5YR6/4), with an average amount of white particles (crushed river shells?), a small admixture of quartz sand, mica and vegetal particles, rare inclusions of black stone.

Outer surface treatment: none.

Firing: regular oxidizing.

Note: minor traces of a white gypsum-like substance on the face.

Publications: Berlev et. al. 2002, cat. 672; Vassilieva 2013, cat. 4.

Analogies: Szymańska 2005, pl. V, cat. 37.

10. Statuette of a naked goddess standing in naos (Fig. 10)

Inv. No.: I, 1a 7973 (KP 374819). From the collection of O.V. Kovtunovich (1986).

Date: 4th–3rd cent. B.C.

Place of discovery: Fayoum.

Preservation: the object is glued together from several parts; chipping and abrasions on the obverse, the figure’s feet lost.

Dimensions: 12.3 × 8.5 cm.

Manufacturing method: impression in a single-sided mould; the front side is of medium quality, the face is poorly elaborated; the reverse is flat, with numerous imprints of vegetal particles (the piece was probably laid to dry on a bed of crushed straw).

Material: alluvial medium-fine hard reddish-brown clay (10R5/6), slightly darker outside (10R5/4), with a significant admixture of mica, a small admixture of white particles (river shells?) and vegetal inclusions, rare inclusions of quartz sand.

Outer surface treatment: smoothed.

Firing: regular oxidizing.

Note: traces of milky white gypsum-like substance on the face, traces of soot on the face and reverse sides in the upper part.

Publications: Berlev, Hodjash 2004, 476, cat. 198.

Analogies: Redford 1988, pl. XXIId; cf. Ashton 2003 (UC 30186); Bailey 2008, No. 3108; Kaufmann 1913, Abb. 69–70; Perdrizet 1921, pl. LXXIX; Török 1995, pl. CVIII–CIX; Weber 1914, Taf. 20.198–199.

ISIS-THERMUTHIS

The figurine I,1a 2740 (see Fig. 1) is a mixamorphous creature: the upper part is an image of a female torso, the lower part (instead of legs) is a serpent’s tail twisted in the form of figure eight. The woman with a serpentine body is dressed in a long chiton and undershirt with fringes, a cloak is slung over her shoulders, the ends of which are tied under her breasts in a characteristic ‘Isis knot’, which in Roman times became one of the goddess’ attributes.3 The tunic’s collar is carelessly open on her chest. Her head is crowned with the characteristic crown of Isis − a basileion with horns, a solar disk, and two feathers. The haircut is neat: it has middle-parted hair, smooth on top and curled on the forehead, it lies on the shoulders in curled locks. Such a hairstyle, according to J. Fisher, is characteristic of the early Severan dynasty.4 Around the woman’s head is arranged a peculiar wreath of fruits, leaves and ears. Spikes of wheat are also present below, beneath the serpent’s tail. In her right hand the goddess holds a long torch, in her left hand she holds a bundle of ears. On the left hand there is a suspended situla − a small ritual vessel, an attribute of the goddess Isis.

4. Fischer 1994, 96

What attracts attention is the superb quality of the execution of this statuette which has no exact parallel: fine modeling of the face with plump cheeks, almond-shaped eyes, the representation of a burly body with lush breasts, thorough elaboration of hair, clothing folds, snake scale, feathers and ears. All known analogies of the same iconographic type5 are much more conventional and flat.

The described iconographic type combines elements of the images of two goddesses − Isis and Renenutet.6 The latter was considered to be the goddess of fertility and harvest and the mother of the grain god Nepri (hence her convergence with Isis as the mother of Horus).7 In the Hellenistic era, Renenutet became known to the Greeks as Thermuthis, as evidenced by the four hymns by Isidoros from Medinet Madi (the Fayoum city of Narmuthis) written in honour of the goddess Isis (3rd–2nd centuries B.C.).8 In these hymns, Isis is identified with many goddesses, including Thermuthis; in some Fayoum inscriptions she is called ‘Isis-Thermuthis’, or ‘Isermuthis.’9 At Narmuthis there was a large temple of Isis-Thermuthis; other small sanctuaries were also built in honour of this goddess in Fayoum, for example at Tebtynis (floruit 1st century B.C. − 1st century A.D.).10 Numerous terracottas found in Egypt demonstrate the popularity of the Isis-Thermuthis’ cult not only in Fayoum, but also in other regions of the country.

7. Vanderlip 1972, 20; Bergmann 1970, 86–85.

8. Vanderlip 1972.

9. Vanderlip 1972, 17. Hymn I.1. See notes 1–3 on p. 19: about two variants of the Greek transliteration (Hermouthis/Thermuthis) of the Egyptian name of the goddess Renenutet (Rnn.wt.t/ Rnn.t). See also: Bricault 2013, 480.

10. Gallazzi, Hadji-Minaglou 2000.

Despite the fact that the ideas reflected in Isidore’s hymns show actual peasant world, we can see here an obviuos influence of the official temple religion, which has created various images of the goddess Isis.11 The composition of the Isis-Thermuthis’ iconography apparently falls on the heyday of Hellenism. This goddess first of all was a guaranty of rich harvest,12 from this function comes the usage of various iconographic attributes − a torch, a sistrum, a cornucopia, ears of corn − stems. The torch is an attribute of several goddesses with whom Isis could associate. Firstly, it is one of symbols of the goddess Demeter − along with ears of wheat, flowers and fruit − as the goddess of fertility, with whom Isis was traditionally identified.13 At the same time, the torch, which obviously indicates the chthonic nature of Isis, also refers to the attributes of the underground goddess Hecate,14 but it may also be a symbol of the goddess Athena.15

12. Dunand 1979, 128–130.

13. Mentioned by many ancient authors, for example: Hdt. II. 59. 156; Diod. I. 13–14, 96; in many aretalogies, e.g: Isidoros. I. 3. 21 (Vanderlip 1972); Chalkis. 2 (Totti 1985, 15–16, Nr. 6).

14. Kaufmann 1913, 86, Abb. 52–53.

15. Bailey 2008, No. 3332.

The symbolism of Isis-Thermuthis emphasizes the chthonic nature of the goddess and her features peculiar to the Greek Demeter, as we have said above. However, in this case we are not talking about syncretism with Demeter, but about the cult of a peculiar agrarian Isis. Sometimes goddesses with similar functions could be depicted side by side: for example, in one Alexandrian relief the Greek Demeter stands together with the serpentiform Isis-Thermuthis and Agathodaemon.16 The mentioned deity is the good demon of Alexandria, who became an incarnation of the Egyptian god Shai, borrowing the serpent form from her female hypostasis − Renenutet (as the goddess of fate).17 Note that various depictions of serpentine creatures associated with chthonic and agrarian symbolism existed for centuries outside Egypt as well – just let us recall the Athenian fertility god Erichthonius.18 In reliefs and small statuary Isis-Thermuthis was sometimes depicted close to traditional Egyptian iconography − with a snake body and a female head, but with an almost unexpressed female torso.19 However, the majority of terracottas represent her with a female torso and serpent legs. The standard set of attributes (which could varied) was as follows: horn of abundance, torch and sistrum; on the head, as a rule, was a ‘basileion’ crown, sometimes with ears on the sides.20

17. Dunand 1967, 9–10; См. Quaegebeur 1975.

18. Dunand 1979, 106, 112; Graves 2001, 25.2, 50.6.

19. Gallazzi, Hadji-Minaglou 2019, 121, cat. 64 (relief from Tеbtynis); Dunand 1967, pl. IA (relief: Alexandria Inv. 3171); Perdrizet 1921, pl. XV, 2 (terracotta).

20. Perdrizet 1921, pl. XV, 4–5.

The figurine of Isis-Thermuthis from the collection of the State Museum of Fine Arts is a fine example of the blending of Egyptian and Greek religious iconography; we are facing a classical, mature syncretic form of the Roman Period, in the manufacture of which the hand of a skilled master can be seen.

ISIS LACTANS

The terracotta figurine I,1a 2902 (see Fig. 2) refers simultaneously to the types of Isis seated on the throne and the so-called nursing Isis, or Isis lactans. But instead of the infant Harpocrates, usually sitting on his mother’s lap, here the bull Apis is shown next to the goddess.

Isis sits on a throne, the high back of which is decorated with a frieze of uraeus cobras. On her head is a floral wreath with a ribbon and a ‘basileion’ crown; long curls fall down on her shoulders from under the headdress. The cloak with fringes is tied on the chest with the characteristic ‘Isis knot’. While the long chiton is tied down to her heels, it leaves the goddess’s breast exposed. On her left hand, she feeds a calf − the young Apis − standing to her left on the altar, the wall of which is decorated with the image of lotus stems. Certain parts of the figurines (the chiton, details of the headdress, the frieze with uraei and the background behind Apis) retained the colour of red ochre over white plaster. Traces of white pigment can be seen on many Graeco-Roman terracottas, which could have been a kind of a base, a ground for applying a color layer. It is also visible on some terracotta figurines found during the excavations in the Fayoum city of Tebtynis.21

In Egyptian terracotta statuary we often find images of Isis sitting on the throne and nursing the infant Harpocrates.22 Isis with suckling infant is one of the most common images of the goddess, dating back to the high antiquity.23

23. The image of Isis (along with Hathor) feeding Horus is especially common in the “mammisi” of Egyptian temples of Graeco-Roman times (see, for example: Tran Tam Tinh 1973, pl. II–IV).

It is known that in Memphis Isis was worshipped in the form of a cow as the mother of the bull Apis; each cow was given a certain name, which included the component ‘Isis’.24 This is confirmed by the epigraphic material from the burials of sacred bulls in the northern part of the Saqqara necropolis.25 According to F. Dunand’s interpretation, the image of Isis giving her breast to Apis is a visible confirmation of the legal rights to the throne of the new bull Apis, the heir of the recently deceased.26 Respectively, such figurines may have been associated with the enthronement of Apis, which also included royal symbolism.27 But it should be borne in mind that the terracotta statuary reflects the popularity of the iconographic image primarily in the sphere of private cult.28

25. Smith 1971, 11−12.

26. Dunand 1979, 61.

27. Ladynin 2018, 35–55.

28. Dunand 1979, 61, No. 105; Török 1995, 88.

The Moscow figurine can be dated by its hairstyle: a similar figurine (Isis on a throne, nursing Harpocrates) is dated to the late 2nd or early 3rd century A.D.29 J. Fischer attributes the type of breastfeeding Isis sitting on a modeled throne to the 2nd century A.D.30 According to S.-A. Ashton, judging by the images on oil lamps, this type follows the iconography of the goddess established at the end of the first century B.C.31

30. Fischer 1994, 341, Nr. 844

31. Ashton 2003, 86.

There is a certain variety of types within this iconography: for example, Isis sitting on a throne and nursing Apis standing on a column (UC 33564).32 This figurine is a good analogy to the Moscow one, but, in contrast to the latter, its preservation is worse − the headdress and the lower part of the sculpture are lost. Another morphological variation is the depiction of Isis, nursing Apis while standing, with the bull also located on a small podium − the altar.33

33. Рerdrizet 1921, 53, pl. XVI, 6; Kaufmann 1913, 68, Abb. 38.

The handle of lamp I,1a 7924 (see Fig. 3), which is a bust-length image of the goddess Isis (the head is not preserved) breastfeeding a child, also belongs to the type of Isis lactans. The bust of Isis is raised from the leaves of the acanthus. The representation of half-busts on an acanthus flower is a very common motive in antique small sculpture.34 This pattern is also used in decoration of the two terracotta handles of the lamps from the Berlin collection, which come from Alexandria and date back to the middle of the 2nd century A.D.35 The material of the Moscow object – light-fired marl clay − also points to the Alexandrian production of this terracotta. This assumption is also supported by archaeological material from the excavations at Marina el-Alamein. The handles from the lamps excavated there were made in the form of terracotta figurines of deities − Isis on the throne, the nursing Isis and Sarapis. At the same time, only one set (E 253)36 − the handle and the lamp itself − survived completely, which is quite rare. This image of Isis nursing Horus is a full analogy to the Moscow terracotta.37 The origin of the terracotta from the region of Alexandria is indicated by other parallels − from Canopus.38

35. Philipp 1972, 26–27. Kat. 28–29.

36. Zych 2004, 84, Fig. 5.

37. Zych 2004, 83–84, fig. 4–5.

38. Breccia 1926, 77, tav. XXXVI, 7 (cf. tav. XXXVI, 2).

It is known that the maternal aspect of Isis prevailed in her image and contributed to the fact that in the late period the majority of mother goddesses in Egypt began to be identified with Isis. Nevertheless, in the golden age of religious syncretism, Isis borrowed not only the functions of fertility (from the Greek goddess Demeter and the Egyptian Renenutet), but also the patronage of sensual love and female fertility (from the Greek Aphrodite and the Egyptian Hathor).39

ISIS – DEMETER – SELENE

Two figurines I,1a 2916 and I,1a 2920 (see Fig. 4–5) depict the goddess Isis with the attributes of the Greek goddesses Selene and Demeter. Both figurines are of good quality and quite interesting, and both are notable for their peculiar iconography.

Figurine I,1a 2916 (see Fig. 4) represents a female figure dressed in a cloak and a long chiton, and standing on sheaves of wheats. The ears of wheat, in turn, rest upon a half-nude female figure holding a wicker basket filled with fruits. This is the personification of Euthenia, the fertile land.40 On the reverse side of the terracotta, folds have been inscribed on the still wet clay, and the same has been done with the ears of wheat behind the figure of Euthenia. The ears and the long cloak belong to the symbolism of Demeter. In this case, we have an example of the complete identification of the goddesses Isis and Demeter, mentioned by Herodotus (Hdt. II. 59, 156).

The figure of the goddess is shown as if flying; this impression is created by the depiction of folds of her long chiton, as if blown by a gust of wind. Above her head, a veil hovers like a sail. The face is framed by short curls. On the goddess’s head there is a small modius and a crescent moon. Exactly this attribute enables to identify the figure with Selene − the Greek goddess of the moon, while the modius is rather an accessory of Demeter.41 However, even goddesses such as Demeter may sometimes receive a lunar crescent.42 In Roman times, in small sculptures there was a widespread type of the so-called Diana Lucifera, i.e. ‘bearing light’, who was depicted standing (on a stand or, more often, on a round sphere), dressed in a long chiton, holding one or two torches in her hands, bearing a half moon atop the head and the veil was blown in a semi-circle over her head, falling on her shoulders and covering her arms and half-bent elbows.43 However, the fully preserved figurines are unknown to us; all the bronze figurines represent the goddess of the moon with broken hands.44 So, the long robe and a wind-blown cloak, which rises in a semicircle over the head and wraps around her arms, a crescent moon atop the head – all these traits show the similarity in iconography. A fairly close analogy from the museum in Karlsruhe, dated to the first half of the 3rd century A.D., is termed as Isis (Demeter)-Selene;45 its exact origin is not specified (“from Egypt”). The clay is notably redder in color (2.5YR4/6) than that of the Moscow figurine, which has a brown surface (7.5YR4/3). A terracotta fragment from the museum in Rostock, depicting a woman with a crescent on her forehead, is called ‘Isis (Demeter/Fortuna/Selene/Nemesis).’46

42. Dunand 1990, 52–53, 75–76.

43. For more, see Aponasenko 2019, 160.

44. For example, Aponasenko 2019, 111, cat. 5: figurine of the 1st century A.D., originating from Rome (Berlin Antikelsammlung. Nr. Fr. 1845). Cf. Aponasenko 2019, 110, cat. 4.

45. Schürmann 1989, 270.

46. Attula 2001, 134, Kat. 50.

The type of terracotta depicting Aphrodite-Selene is very well known: a standing nude female figure, a crescent moon atop her head, and fluttering clothes above the figure.47 The motif of the cloak fluttering over the head is found in Hellenistic terracottas depicting Aphrodite, for example, from the Greek necropolis of Myrina in Asia Minor.48 However, in Moscow item the symbolism associated with Aphrodite is indicated only by two large rose flowers near the face. The main attribute of the goddess Aphrodite − nudity − is missing.

48. Mollard-Besques 1963, pl. 32a (LY 1557), 34c (MYR 49), 36b (MYR 39), 36d (MYR 38), 37a–f.

The iconography of lower part of the figurine I,1a 2920 (see Fig. 5) is completely similar to the figurine I,1a 2916: lush folds of the chiton, as if blown by the wind; a large cape; below − the allegorical figure of Euthenia, lying on sheaves of ears. The tracing on wet clay of the ears of wheat and the folds of the garment on the back of the object are also identical. Moreover, the clay of both objects is similar, which leads us to assume that they were made in the same workshop and in the same pottery series. However, the head of the figurine I,1a 2920 is completely different, a round-faced, with a lush hairdo, arranged in braids and with a floral wreath. The old Inventory book rightly states that this head is from another figurine.

Indeed, it is clearly visible that the head and body of terracotta I,1a 2920 are rather crudely joined together using a grayish-white gypsum-like substance. Actually it is impossible to say whether this restoration was undertaken in Roman times or already in the 19th century at the request of an Egyptian antiquity dealer in order to increase the cost of the object. After all, many terracottas have traces of white plaster, the presence of which could mislead the purchaser. It is unlikely that V.S. Golenischev was deceived in this purchase, considering that he possessed a complete figurine of the same type in his collection. This object is an interesting example of human entrepreneurial spirit.

A complete parallel to the terracotta head I,1a 2920 was found in the 2014 sales catalogue of New York’s Royal-Athena Galleries: in 1993, the object was sold in Great Britain at Christie’s, with the indication of origin from Alexandria and with the dating to the ca. 1st century A.D.49 Now we can say with certainty that the head for I,1a 2920 was borrowed from a figurine of a completely different type − the so-called oranta with raised hands.

ISIS − APHRODITE – ANASYROMENE

Figurine I,1a 2929 (see Fig. 6) depicts a woman in a chiton with the characteristic Isis knot on her chest. Unfortunately, the entire lower part of the statuette has been lost. Nevertheless, by analogy, we attribute this depiction to the type of the so-called Isis-Aphrodite-Anasyromene (Anasyrmene) − the standing goddess Aphrodite lifting the skirt of her dress and exposing the intimate parts of her body. Such statuettes were discovered at the excavations of Athribis in a domestic context.50 Many fragments of similar figurines of Aphrodite (late 3rd to the first half of the 2nd century B.C.) were found in tombs of the Alexandrian necropolis of Mustafa Pasha.51

51. Fischer 1994, 81, Anm. 73.

Figurine I,1a 2929 belongs, judging by analogies, to the Hellenistic period. It represents the goddess Aphrodite-Anasyromene identified with Isis, as attested, firstly, by the purely Greek iconography, and finally, by the headdress, representing the attributes both of Aphrodite (two floral wreaths being in the form of rolls, and the third of leaves), and of Isis (a royal crown of two feathers with a solar disk). One of the wreaths is crossed by a wide ribbon; the basileion of Isis is at the top of the floral wreath. Locks of curly hair are spread over the shoulders. The figurine shows traces of pinkish-white smudge, blue and red paint.

The motif associated with lifting the skirt of a dress and exposing intimate body parts is well known from the text of the Egyptian New Kingdom Trial of Horus and Seth: the goddess Hathor raised up her skirt, exposing her genitals in front of her father Ra in order to cheer him up.52 Herodotus reports that during the festival at Bubastis ‘some of the women make a noise with rattles, others play flutes all the way... and others stand up and lift their skirts’ (Hdt. II. 60). Diodorus reports about ritual actions during the funeral of the bull Apis, noting that only women can stand in his presence and while doing so they raise their robes and expose their genitals (Diod. I. 85. 3). Both festivals are connected with the fertility cult; the women involved obviously perform ritual dances and demonstrate ritual gestures, just the same as those shown on the terracotta figurines. H. Szymanska directly connected this type of representation with the report of Diodorus about the rituals in honor of Apis.53

53. Szymańska 2000, 81.

‘NAKED GODDESS’ OR ISIS APHRODITE?

Figurine I,1a 2848 (see Fig. 7) is a standing nude woman whose arms are stretched out along her body and tightly pressed against it. The legs are tightly closed (their lower part is not preserved). Her breasts and abdomen are emphasized. The basileion, a royal crown of Isis, is placed upon the calathus.

The style of this figurine is similar to that of the early Ptolemaic terracotta figurines from the workshops of Athribis in the Eastern Delta. The presence of archaic features has been noted by the researchers.54

Figurine I,1a 6889 (see Fig. 8) depicts a young nude woman with hands pressed to her hips. The woman has long legs, thin waist, slightly protruding abdomen and well shaped breasts. The body surface is poorly modeled, with marked folds under the abdomen and on the neck. Well-modeled, however, are the facial features, such as large almond-shaped eyes, a long nose, and puffy lips. The surface of the nose is slightly damaged. Middle-parted hair over her forehead are arranged in a rich hairstyle with short quiff; carefully curled locks fall over her shoulders. The hairstyle looks reminiscent of the corkscrew curls in the portraits of Hellenistic queens of the 2nd and 1st centuries B.C.55 The head of the goddess is crowned with a complicated and high headdress consisting of four floral wreaths put one atop the other. The lower wreath is tied with ribbons and decorated with leaves and flowers. Two ribbons with garlands of ivy leaves descend on the woman’s shoulders up to her elbows, which, as well as the headdress, resemble the style of the ribbons on the ceramic alabastra of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts I, 1a 2845, I, 1a 2863, and I, 1a 7991 dated to the late Ptolemaic and Roman Periods.56

56. Vassilieva, Malykh 2016, 988–993.

A noteworthy feature of this figurine is the advanced right leg. Usually similar terracotta figurines generally depict a standing woman figure with legs tightly closed.57 However, the recently conducted restoration and visual analysis of the clay showed that the lower part of the legs was not a later addition (as has been previously thought) but quite authentic attitude. Thus we have an example of the unique iconographic type of a walking ‘naked goddess’.

By analogies from the other museum’ collections we can imagine how such a figurine could have been painted: ribbons of wreaths – in yellow, blue, red colours; flower buds – in bright pink; garlands of ivy leaves – in emerald green; locks of hair and eyes – in black.58

Similar figurines of the ‘naked goddess’ can be dated to the early Roman Period (1st–2nd cent. A.D.).59 It is intended, of course, the standard type of the goddess standing to attention and her legs joined; meanwhile the ‘stephane’ wreaths can be arranged on her head not only horizontally, but also vertically, in the form of ‘halo’ circles superimposing one upon the other. Some of the figurines have an archaeological context and come from the Delta, such as the terracotta found in Tanis (in the dwelling house to the East of the ‘great temple’).60

60. Petrie 1885, 42, frontispiece, No. 11; Favard-Meeks 1998, 126, pl. XXII, 11 (British Museum, EA 22153).

The head of the female statuette I,1a 2803 (see Fig. 9) is bearing a hairdo with curled locks and a small floral wreath of Aphrodite. The wreath has a wide ribbon. The upper part of the headdress is not preserved, but this fragment indicates that there once should have been a calathus and a crown of Isis; similar heads were found in Athribis.61 On the basis of these hypothetical reconstructed elements, the head from the Moscow collection may be considered as a depiction of Isis-Aphrodite.

This type of terracotta figurines was widespread in Egypt from the end of the 4th century B.C. up to the 3rd century A.D. There are several points of view in historiography regarding the interpretation of the figurines. Sometimes this type of figurines has been called ‘concubines’ or ‘brides’ of the dead,62 less often ‘idols’ or ‘dolls.’63 However, such figurines were found not only in men’s burials, they also come from houses, public buildings (thermae) and sanctuaries.64 The erotic aspect of such depictions was emphasized by the nudity and the accent on purely female forms, especially the abdomen and thighs.

63. Kaufmann 1913, 102–103, Abb. 70.

64. Griesbach 2013, 24–30.

It is more widespread to designate such figurines as Isis-Aphrodite.65 The goddess Aphrodite, who in Graeco-Roman times was identified with Hathor, was extremely popular in Hellenistic Egypt; her cult was founded by Queen Arsinoe, wife of Ptolemy Philadelphus.66 The identification of Isis and Aphrodite, recorded in numerous objects of small sculptures from the 3rd century B.C. onwards, is due to some comparable functions of both goddesses, connected with love, beauty and femininity.67 At the same time, the term ‘Isis-Aphrodite’ is often used (as a synonym) along with ‘Hathor-Aphrodite’68 or simply ‘Hathor.’69

66. Fraser 1972, I, 197.

67. Bricault 2013, 484.

68. Ashton 2003, 84 (UC 48077).

69. Bailey 2008, No. 2995, 2997, 3000; Walker, Higgs 2001, 108–109, cat. 133; Weber 1914, Taf. 21, 200, 206.

In some contributions one can encounter such an apellation: ‘figurine of fertility or nude Isis-Aphrodite’;70 thus combining two variants of interpretation at once. Strictly speaking, in most cases these figurines have no Isiac attributes and the identification of Isis with the ‘goddesses of fertility’ remains problematic,71 although possible, taking into account the specificity of image of the myrionymous goddess.

71. Dunand 1990, 16.

More and more researchers are inclined to designate the forenamed type of terracotta as a ‘naked goddess,’72 because the nudity and a specific headdress (a floral wreath and/or calathus) belong to the iconography of different goddesses of love and fertility, from Aphrodite to Demeter and Isis. It should be noted that nudity was rather a feature of the Middle Eastern goddesses of fertility and sensual love, such as Ishtar or Hathor. The development of the type of the naked goddess dated back to the Early Hellenistic Period.73

73. Fischer 1994, 73–75.

The archaeological context of these figurines is diverse, with finds in houses and burials prevailing. A large amount of mass production was found in a villa in Athribis (2nd–3rd cent. A.D.),74 from the same place come terracotta figurines of Isis-Aphrodite found in the context of public buildings (thermae).75 Numerous figurines of the ‘naked goddess’ made of various materials (including terracotta) were found in a domestic context in Tanis (1st–2nd cent. A.D.).76 Heracleopolis Magna,77 Karanis (in the underground structures of granaries).78 Perhaps these were foundation deposits under buildings.79 The use of statuettes in living quarters can be easily explained by their symbolism of fertility, which bears the iconography of this kind of figurines. Depictions of ‘nakes goddesses’ were also common in funerary equipment, both in the burials of adults and children.80 The predominance of figurines of Isis-Aphrodite may be connected with the idea of the magical power of Isis, who revived Osiris.81 Therefore the terracottas representing the ‘naked goddess’ were also in demand for this − posthumous − side of life. The function of such figurines is not entirely clear; they could have been ex voto as protection of married life and a guarantee of a woman’s fertility; being the votive offerings, they could also serve as funerary figurines and contribute to rebirth in the other world.

75. Szymańska 2005, 37–41.

76. Petrie 1885, 41–50.

77. Petrie 1905, 27–29.

78. Gazda et al. 1978, 67.

79. Griesbach 2013, 29.

80. Weber 1914, 129–134, Nr. 202; Griesbach 2013, 31.

81. Bayer-Niemeier 1988, 43; Fischer 1994, 75, Anm. 16; Griesbach 2013, 30.

‘UNNAMED NAKED GODDESS’

Figurine-plaque I,1a 7973 (see Fig. 10) depicts a standing nude woman inside a naos. The woman is shown wearing a short round wig, standing at attention, her arms lying along her body. The abdomen and breasts are emphasized. The figurine probably have once been painted, as the plasterlike ground on the front is present in places. The fact that the figure is depicted standing in a small sanctuary pointed to its divine status. The portico of the small temple is rectangular, with a horizontal lintel resting on two columns represented in the form of papyrus stems. Adjacent to these tall columns are two other, lower ones, with lotus-shaped capitals (the right column cap is split off). At the base of the two columns there are two symmetrical figures of reclining lions: the figures are poorly preserved, but judging by analogies we can say with certainty that they are lions.82

Representations of goddesses inside temples are often found in small statuary, but, as a rule, the figure is shown in a Hellenized pose,83 often inside a Greek temple with a triangular pediment, but sometimes in an Egyptian naos with cobras-uraei.

The exact attribution of this kind of figurines is hardly possible. D. Bailey aptly defined this group of images as a ‘nameless goddess,’84 while calling each item as ‘a shrine with a naked goddess.’85 This interesting group includes representations of the goddess without any attributes. The parallels to this type go back to the period of the XXX dynasty covering the area from Tanis, Mendes, Naucratis and Memphis to Heracleopolis. The pose of goddesses is similar to the depictions of Hathor in Ptolemaic and Roman times, but the identification with them is not necessary. It is worth noting that R. Higgins who published material of Greek terracottas from the collection of the British Museum called a similar figure from Naucratis ‘Greek Aphrodite’ and dated it to the end of the 7th century B.C.86 Similar plaques are also known from the Fayoum oasis: nude women standing inside a room similar to the naos or aedicula, often with a little girl by their side.87 K. Kaufman qualifies them as votive palettes, figurines for bestowing offspring, and amulets of fertility − a kind of petition and gratitude for assistance in childbirth and in birth of a healthy infant. K. Kaufmann compares these votive plaques with ‘Aphrodite’ and the so-called naked goddess, images of which were found in the themenos of the temple of Aphrodite in Naucratis.88 D. Bailey also suggests that such images were used as ex votos to temples.89

85. Bailey 2008, 41–42, No. 3108–3110.

86. Higgins 1954, 404, No. 1542.

87. Kaufmann 1913, 102, Abb. 69–70.

88. Kaufmann 1913, 103, Abb. 70.

89. Bailey 2008, 19.

E. Bayer-Niemeier ascribes the depictions of two female figures, the big and the smaller one (a girl?), standing inside a naos with lotus-shaped columns,90 to the type of ‘votive offerings associated with fertility and sexuality.’91 Similar fgurines of women are defined by L. Török as ‘fertility ex-voto.’92 Another variation of this type is the depiction of nude women standing not inside the naos, but as if leaning against a stele with an oval top.93 A similar type of figurines on stone plaques is found in the collection of Vladimir Golenischev (Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts I,1a 5887 and 5914) and dates to the Ptolemaic Period; these plaques depict women standing against the background of a rectangular niche.94

91. Bayer-Niemeier 1988, 148, Kat. 266, 267.

92. Török 1995, pl. CVIII, CIX, No. 202–209

93. Bayer-Niemeier 1988, 148, Kat. 263–265.

94. Berlev, Hodjash 2004, 477, 479, Kat. 199, 201. Ср. Schürmann 1989, Taf. 172, No. 1037 – a plaque with a woman with her right arm bent at the elbow.

Indeed, these images were likely votive offerings to the temples. Numerous images of the goddess of this type were found in Memphis in deposits containing cult objects that had once been used in the temple, but then had been hidden as useless. In another cache, near the sacred lake at Mendes, the plaques depicting a “naked goddess” (or Isis-Aphrodite) were found: the clay plates show nude women inside a naos, with their legs joined together and their hands at their sides.95

Various analogies suggest that the goddess could be named as Aphrodite and Cybele (cf. the stele of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts depicting the Asian goddess Kedshet standing on a lion),96 originating from the Levant, while her prototype could have been Astarte, the goddess of the Bronze Age era; this is indicated by such details as lion figures on the base of the column, the capitals in the form of the head of Hathor or the images of Bes on the column shaft, − details found in other variations of this type.97 In fact, these are different images of the so-called Eastern goddess, to which we can also refer the ‘naked goddess’ or the ‘Eastern Aphrodite’ (Isis-Aphrodite), discussed above.

97. For references to analogies, see Bailey 2008, 20.

The dating of this type of figurines taking into account different variations, generally covers the duration from the Late Period (Sais) to the Early Hellenistic Period.98

Thus, the type of the ‘unnamed goddess’ should be ascribed to the same circle of fertility goddesses as the ‘naked goddess’ and Isis-Aphrodite, but without any specific attributes.

The Moscow collection of terracottas depicting Graeco-Roman Isis in different forms and with various attributes testifies to the diversity of iconographic images of the goddess, which were intended to embody in a small figurine several functions connected with the most important aspects of life in the Ptolemaic and Roman Periods. Given the lack of data on the terracottas’ findspots, it is difficult to say whether the views on the syncretic image of Isis were spread throughout Egypt or whether they were connected with the most important urban centers of Graeco-Roman Egypt concentrated on the Mediterranean coast, in the Delta and the Fayoum Oasis; all these regions being main areas of findspots of terracotta figurines of Isis. Visual analysis of the clay fabrics of the Moscow figurines does not allow us to determine their place of origin, although the texture and admixtures of the clay are more similar to those of the Fayoum and Middle Egyptian clays than to those of the Delta. In addition, the available material does not allow to identify whether certain iconographic variations of the image of Isis belong to specific geographic locations or production centers, which is primarily due to the wide variation of the image of the goddess in Graeco-Roman times.

Figurines depicting the goddess Isis reflect in one way or another the phenomenon common to her syncretic image − in Graeco-Roman Period this polyonymous goddess was identified with a large number of goddesses of the Egyptian and Greek pantheon. The best illustration of such syncretism is the iconographic types of Isis-Thermuthis and Isis-Demeter-Selene. Similar hybrids are typical of Roman times, when the goddess appears in different shapes illustrating her various incarnations: the coroplasters used the iconography of diverse deities to represent the multiple functions of Isis. Most of the traditional depictions of the goddess Isis show her as a woman holding the child Horus in her arms, which indicates the predominance of maternal functions in her image.99 In the Moscow collection there are only a few images demonstrating this aspect − the fragment of the lamp’ handle with a figure of Isis lactans.

Among the variants of the iconography of the so-called naked goddess, researchers count 64 (!) sub-types.100 The greatest variability is observed in the shape of a headdress. It was usually interpreted by coroplasters as a floral crown, which could also be understood as a Greek calaphus. Sometimes the floral motif could be executed in the form of an applique work. A floral crown or calaphus may lie upon one, two, rarely upon three wreaths, which are tied obliquely with a ribbon or a thin garland, sometimes leaves can be seen near the face. Jewelry on the neck are rarely present, even more rarely are the pendants.

As it becomes clear from the above examples, there were two variants of images of the so-called naked goddesses: the first represented female figures with a floral wreath/wreaths and garlands on their heads; the second depicted women with a wreath and/or calathus/basileion on their heads. The first version can be considered as a mere ‘naked goddess’, the second − due to the attributes of Isis – as the goddess Isis-Aphrodite. Thus the Moscow figurine I,1a 6889 belongs to the first variant, and the figurine I,1a 2848 to the second one. The position of the arms and legs of such figurines (with the joint legs and the arms resting along the hips, at side) is typical for the Egyptian visual canon, but generally this type demonstrates an interesting example of borrowing from the Greek tradition of iconography. It is worth noting that the Moscow figurine I,1a 6889 is just a deviation from this artistic principle, however the advanced leg is precisely an element of Egyptian statuary101 (for the Greek tradition the contraposto technique is characteristic). The depictions of the so-called nameless goddess are also executed within the framework of the Egyptian canon and are associated with the symbolism of fertility.

There are several variations of the image of Aphrodite-Anasyromene;102 her headdress is similar to that of the ‘naked goddess’, but the crown usually rests upon more number of wreaths and the decorations are present − garlands, flowers and leaves.103 There is also variability in pose − for example, there is a slight contraposto104 in the position of legs, sometimes the hands of the figurine don’t hold the skirt of the dress, but are lowered to the hips.105

103. Fink 2008, 294.

104. Fink 2008, 291, Abb. 4.

105. Fink 2008, 296, Abb. 5.

The Aphrodite-Anasyromene type, to which the figurine I,1a 2929 belongs, is close in its semantic content to the so-called naked goddesses. Both types are closely related not only to the idea of fertility, but also give emphasis on sexual attraction.106 While making the distinction between Aphrodite and Aphrodite-Anasyromene, it is necessary to consider the atmosphere of religious syncretism in Graeco-Roman Period, when Greek, Egyptian and Near Eastern goddesses were identified with each other, and thus borrowing different functions. Therefore the figurine of a ‘naked goddess’ with a particular set of attributes could be regarded in the appropriate context as Isis, Aphrodite and even Astarte, i.e. as a goddess connected not only with maternity and fertility, but also with love and eroticism. Aphrodite-Anasyromene and the ‘naked goddess’ in particular were associated with the image of the Eastern goddess.107 The relatively small size of such figurines (maximum height about 40 cm, and often much more smaller) may indicate their votive function, which indicates the popularity of images of this kind among ordinary people.108

107. Fischer 1994, 85, Anm. 130.

108. Bricault 2013, 485.

In the Moscow collection the type of figurines with the iconography of Isis-Aphrodite or the so-called naked goddess is the most numerous. The images of Isis-Aphrodite-Anasyromene and the ‘unnamed goddess’ are essentially a variation of the Isis types identified with Aphrodite and the ‘naked goddess’. The identification of terracottas from the Roman Period with Isis becomes particularly problematic because the figurines show the goddess in a variety of forms; their dating sometimes also floats within half a century or even a century (mid-1st to 2nd centuries A.D.).109

During the process of religious syncretism the image of a female deity with various attributes characteristic for many goddesses (Isis, Demeter, Aphrodite, Selene, Thermuthis) has been formed; this phenomenon allowed the coroplasts to create different versions of figurines intended both for cult actions in temples and for domestic sanctuaries. In fact, in the terracottas of Graeco-Roman Egypt the composite image of the goddess Isis, developed on the basis of the Egyptian tradition, with the addition of traits of the goddesses of Greek and Eastern pantheons, highlighting aspects of motherhood and femininity, received a visual embodiment.

Библиография

- 1. Aponasenko, A.N. (ed.) 2019: Viktoria Kal’vatone: sud’ba odnogo shedevra. Katalog vystavki [The Calvatone Victory: The Fate of a Masterpiece. Exhibition Catalog]. Saint Petersburg.

- 2. Ashton, S.-A. 2003: Petrie’s Ptolemaic and Roman Memphis. London.

- 3. Attula, R. 2001: Griechisch-römische Terrakotten aus Ägypten. Bestandskatalog der figürlichen Terrakotten. Rostock.

- 4. Bailey, D. 2008: Catalogue of the Terracottas in the British Museum. Vol. IV. Ptolemaic and Roman Terracottas from Egypt. London.

- 5. Bayer-Niemeier, E. 1988: Liebieghaus – Museum alter Plastik. Bildwerke der Sammlung Kaufmann. Bd. I. Griechisch-römische Terrakotten. Frankfurt.

- 6. Bergmann, J. 1970: Isis-Seele und Osiris-Ei. Zwei дgyptologische Studien zu Diodorud Siculus I. 27. 4–5. Uppsala.

- 7. Berlev, O.D., Hodjash, S.I. 2004: Skulptura drevnego Egipta v sobranii GMII im. A.S. Pushkina [Sculpture of ancient Egypt in the collection of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. Moscow].

- 8. Berlev, O.D., Vassilieva, O.A., Dyuzheva, O.P. et al. (eds.) 2002: Put’ k bessmertiyu. Pamyatniki drevneegipetskogo iskusstva v sobranii GMII im. A.S. Pushkina. Katalog vystavki [The Path to Immortality. The Monuments of Ancient Egyptian Art in the collection of the Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts. Catalogue of the Exhibition]. Moscow.

- 9. Boutantin, C. 2006: Production de terres cuites et cultes domestiques de Memphis à l’époque impériale. Chronique d’Égypte 81/161–162, 311–334.

- 10. Breccia, E. 1926: Le rovine e i monumenti di Canopo: Teadelfia e il Tempio Pneferôs. Bergamo.

- 11. Breccia, E. 1934: Terrecotte figurate greche e greco-egizie del museo di Alessandria. (Monuments de l’Égypte gréco-romaine, II.2). Bergamo.

- 12. Bricault, L. 1994: Isis-Myrionyme. In: C. Berger, G. Clerc, N.-Ch. Grimal (eds.), Hommages а Jean Leclant. Vol. III. Études isiaques. Le Caire, 67–86.

- 13. Bricault, L. 2013: Les cultes isiaques dans le Monde Gréco-Romain. Documents réunis, traduits et commentés par L. Bricault. Paris.

- 14. Dunand, Fr. 1967: Les représentations de l’Agathodémon. Bulletin de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale 67, 9–48.

- 15. Dunand, Fr. 1979: Religion populaire en Égypte Romaine. Les terres cuites isiaques du Musée du Caire. Leiden.

- 16. Dunand, Fr. 1990: Catalogue des terres cuites gréco-romaines d’Égypte. Paris.

- 17. Eisenberg, J.M. (ed.) 2014: Art of the Ancient World. Greek, Etruscan, Roman, Byzantine, Egyptian, and Near Eastern Antiquities. Royal-Athena Galleries. Vol. XXV. New York–London.

- 18. Ewigleben, C., Grumbkow, J. von. (Hrsg.) 1991: Götter, Gräber und Grotesken. Tonfiguren aus dem Alltagsleben im römischen Ägypten. Hamburg.

- 19. Favard-Meeks, C. 1998: Mise à jour des ouvrages de Flinders Petrie sur les fouilles de Tanis. In: P. Brissaud, Ch. Zivie-Coche (eds.), Tanis: Travaux récents sur le Tell Sân el-Hagar. Mission française des fouilles de Tanis 1987–1997. Paris, 101–178.

- 20. Fink, M. 2008: ‘Näckte Göttin’ und Anasyroméne. Zwei Motive – eine Deutung? (I. Teil). Chronique d’Égypte 83/165–166, 289–317.

- 21. Fischer, J. 1994: Griechisch-Römische Terrakotten aus Ägypten. Die Sammlungen Sieglin und Schreiber. Dresden, Leipzig, Stuttgart, Tübingen. Tübingen.

- 22. Fjeldhagen, M. 1995: Catalogue Graeco-Roman Terracottas from Egypt. Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek. Copenhagen.

- 23. Fraser, P.M. 1972: Ptolemaic Alexandria. Vol. I–III. New York.

- 24. Gallazzi, C., Hadji-Minaglou, G. 2019: Trésors inattendus. 30 ans de fouilles et de coopération à Tebtynis (Fayoum). Le Caire.

- 25. Gallazzi, C., Hadji-Minaglou, G. 2000: Tebtynis I. La reprise des fouilles et le quartier de la chapelle d’Isis-Thermouthis. (Fouilles de l’Institut français d’archéologie orientale, 42). Le Caire.

- 26. Gazda, E.K., Hessenbruch, C., Allen M.L., Hutchinson, V. 1978: Guardians of the Nile. Sculptures from Karanis in the Fayoum (c. 250 BC–AD 450). Ann Arbor.

- 27. Graves, R. 2001: Mify drevney Gretsii [The Greek Myths]. Moscow.

- 28. Грейвс, Р. Мифы древней Греции. Пер. К.П. Лукьяненко под ред. А.А. Тахо-Годи. М.

- 29. Griesbach, J. (Hrsg.). 2013: GRYPTISCH. Griechisch–Ägyptisch. Tonfiguren vom Nil. Würzburg.

- 30. Higgins, R.A. 1954: Catalogue of the Terracottas in the Department of Greek and Roman Antiquities British Museum. Vol. I. Greek, 730–330 B.C. London.

- 31. Hodjash, S., Berlev, O. 1982: The Egyptian Reliefs and Stelae in the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts, Moscow. Leningrad.

- 32. Hussein, Nahla Mohamed Ahmed. 2016: Kiman Fariss, Krokodilopolis in griechisch-römischer Zeit: archäologische Untersuchung der Terrakotta-Figuren. PhD Diss., Freien Universität. Berlin.

- 33. Jucker, H. 1961: Das Bildnis im Blätterkelch. Geschichte und Bedeutung einer römischen Porträtform. Bd. I–II. Olten.

- 34. Kaufmann, C.M. 1913: Ägyptische Terrakotten der griechisch-römischen und koptischen Epoche. Cairo.

- 35. Ladynin, I.A. 2018: [Life and death of one Apis: from the second Persian rule to the satrapy of Ptolemy]. In: Drevniy Vostok i Antichnyy mir. Sbornik nauchnykh trudov kafedry istorii drevnego mira istoricheskogo fakul’teta MGU. Vyp. 9 [Ancient East and Ancient World. Collection of Scientific Works of the Department of the History of the Ancient World of the Historical Faculty of the Lomonossov Moscow State University. Issue 9]. Moscow, 35–55.

- 36. Lintz, Y., Coudert, M. (dir.) 2013: Antinoé. Momies, textiles, céramiques et autres antiques. Paris.

- 37. Livshits, I.G. (ed.) 1979: Skazki i povesti drevnego Egipta [Tales and Stories of Ancient Egypt]. Leningrad.

- 38. Mollard-Besques, S. 1963: Musée Nationale du Louvre. Catalogue raisonné des figurines et reliefs en terre cuite grecs, étrusques et romains. II. Myrina. Illustrations. Paris.

- 39. Myśliwiec, K., Bakr Said, M. 1999: Polish-Egyptian excavations at Tell Atrib in 1994–1995. Études et Travaux 18, 180–219.

- 40. Pavlov, V.V., Hodjash, S.I., 1985: Egipetskaya plastika malykh form [Egyptian Plastic of Small Forms]. Moscow.

- 41. Penna, V. (ed.) 2016: Heads and Tails. Tales and Bodies. Engraving the Human Figure from Antiquity to the Early Modern Period. Ghent.

- 42. Perdrizet, P. 1921: Les terres cuites grecques d’Égypte de la collection Fouquet. Paris.

- 43. Petrie, W.M.F. 1885: Tanis. Bd. I. 1883–1884. London.

- 44. Petrie, W.M.F. 1905: Roman Ehnasya (Herakleopolis Magna) 1904. London.

- 45. Philipp, H. 1972: Terrakotten aus Ägypten im Ägyptischen Museum Berlin. Berlin.

- 46. Quaegebeur, J. 1975: Le Dieu йgyptien Shai dans la religion et l’onomastique. Leuven.

- 47. Redford, S. 1988: The first season of excavations at Mendes (1991). Journal of the Society of the Studies of Egyptian Antiquities 18, 49–79.

- 48. Schürmann, W. 1989: Katalog der antiken Terrakotten im Badischen Landesmuseum Karlsruhe. Göteborg.

- 49. Smith, H. 1971: Preliminary report on the excavations at North Saqqâra, 1969–1970. Journal of Egyptian Archaeology 57/1, 3–13.

- 50. Smith, H. 1972: Dates of the obsequies of the Mothers of Apis. Revue d’égyptologie 24, 176–187.

- 51. Stanwick, P.E. Portraits of the Ptolemies. Greek Kings as Egyptian Pharaohs. Austin, 2002.

- 52. Szymańska, H. 2000: Tell Atrib excavations 1999. In: M. Gawlikowski, W.A. Daszewski (eds.), Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean XI. Reports 1999. Warsaw, 77–82.

- 53. Szymańska, H. 2005: Terres cuites d’Athribis. Turnhout.

- 54. Török, L. 1995: Hellenistic and Roman Terracottas in Egypt. Roma.

- 55. Totti, M. 1985: Ausgewahlte Texte der Isis-Serapis-Religion. (Subsidia Epigrapha, 12). Hildesheim–New York.

- 56. Tran Tam Tinh, V. 1973: Isis Lactans. Corpus des monuments gréco-romains d'Isis allaitant Harpocrate. (EPRO, 37). Leiden.

- 57. Vanderlip, V.F. 1972: The Four Hymns of Isidoros and the Cult of Isis. (American Studies in Papyrology, 12). Toronto.

- 58. Vassilieva, O.A. 2013: [Terracottas from the collection of the State Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts: Representations of the Isis]. Trudy Gosudarstvennogo Ermitazha. T. LXVI. Peterburgskie egiptologicheskie chteniya 2011–2012 [Transactions of the State Hermitage Museum. Vol. 66. St. Petersburg Egyptological Readings 2011–2012]. Saint Petersburg, 55–67.

- 59. Vassilieva, O.A., Malykh, S.E. 2016: [Ancient Egyptian relief ceramics of Greek-Roman times from the collection of Pushkin State Museum of Fine Arts]. Vestnik drevney istorii [Journal of Ancient History] 76/4, 981–1010.

- 60. Walker, S., Higgs, P. (eds.). 2001: Cleopatra of Egypt. From History to Myth. London.

- 61. Weber, W. 1914: Die ägyptisch-griechischen Terrakotten. (Königliche Museen zu Berlin. Mitteilungen aus der ägyptischen Sammlung, II). Berlin.

- 62. Zych, I. 2004: Marina El-Alamein. Some ancient terracotta lamps from Marina. In: M. Gawlikowski, W.A. Daszewski (eds.), Polish Archaeology in the Mediterranean XV. Reports 2003. Warsaw, 77–90.

2. Bricault 1994.