- Код статьи

- S032103910015611-5-1

- DOI

- 10.31857/S032103910015611-5

- Тип публикации

- Статья

- Статус публикации

- Опубликовано

- Авторы

- Том/ Выпуск

- Том 81 / Выпуск 2

- Страницы

- 684-697

- Аннотация

The article is devoted to three tombstones from the excavations of Chersonesos in Taurica. Two gravestones preserved the names of the buried persons: Aurelius Viator and Sabinus; the third is nameless. The portraits of the buried are carved on the monuments. Each of them holds a bird in his hands. Judging by numerous analogies, birds were a common attribute of children’s funeral portraits in antiquity and became a symbolic indication of childhood, as they were common pets. Keeping and caring for pets was an important part of education and a favorite pastime for children in the Roman Empire.

- Ключевые слова

- Chersonesos in Tauris, tombstone, Aurelius Viator, Sabinus, portrait, children, birds, soldier’s clothes, everyday life

- Дата публикации

- 28.06.2021

- Год выхода

- 2021

- Всего подписок

- 11

- Всего просмотров

- 191

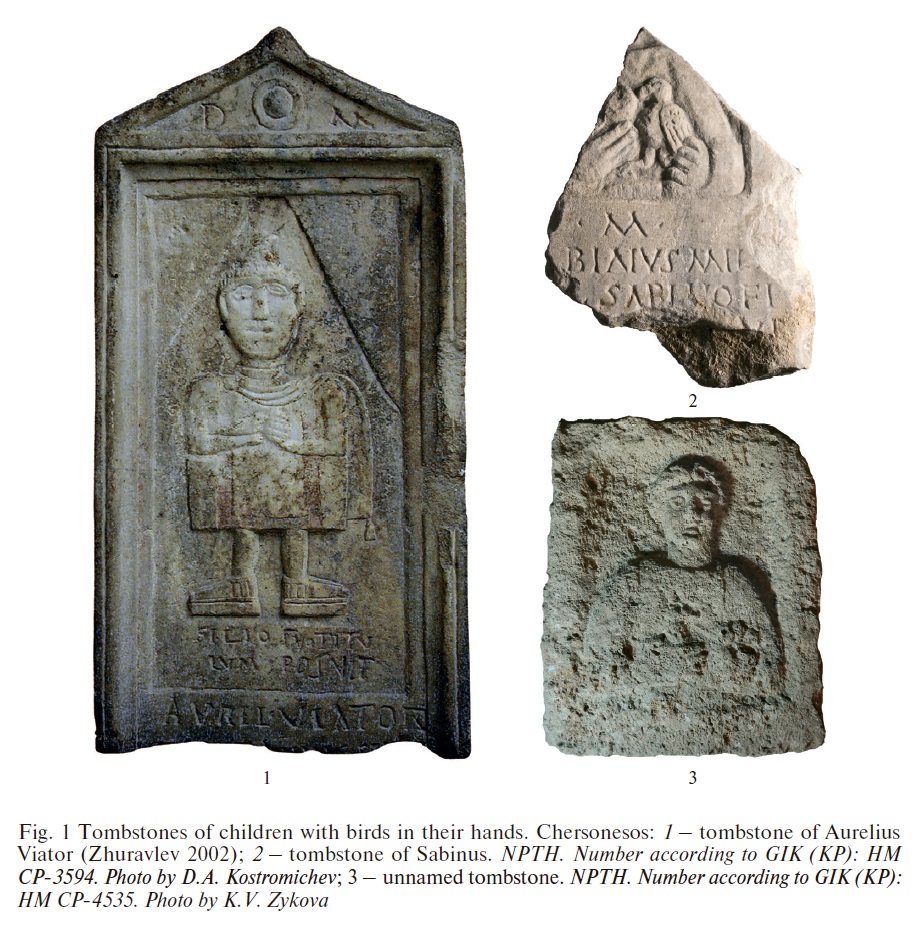

In 1892, during the excavations of the southern section of Chersonesos in Taurica’s necropolis, a marble burial stele with a Latin epitaph and a fully preserved image of the deceased was discovered (Fig. 1, 1). The stele was used for the second time as one of the stones for the lining of a child's grave (No. 77), which had been looted before excavations1. At present, the monument is kept in the collection of the State Historical Museum2. The stele has been repeatedly published with descriptions of the text's image, translations, and commentaries3. The date of the monument is determined within the 3rd century A.D. 4

In the upper part of the stele in the edicule, a full-length frontal view of the entombed man is depicted. He is dressed in a short tunic, with a cloak fastened with a fibula, a pointed cap on his head, holding a bird and fruit in his hands. At the bottom of the burial stele there is a Latin epitaph. The first four lines of the inscription are fully preserved5: D(is) M(anibus)./ Filio suo titu/ lum posuit/ Aurel(io) Viatori/ [---] – "To the gods Manes. To son Aurelius Viator put a tombstone inscription... ."

The end of the text has not been preserved. V. V. Latyshev believed that Aurelius Viator dedicated the inscription, and the name of his son was not mentioned6. E. I. Solomonik defined that the name of Aurelius Viator was given in the dative case. It was Aurelius` father who dedicated the tombstone to his son7. This observation signifies the identity of the name and the person portrayed on the tombstone. The reading by Solomonik has not been further challenged.

7. Solomonik 1983, 68.

Despite the clarity of the text and completeness of the image, there is still no unanimous understanding of the monument. Researchers have been split up as to the social affiliation of the buried man. Two views emerged, each based on either the text of the inscription or the iconography of the image. Both versions have several proponents. Based on the text, the epigraphers speculated that Aurelius Viator was the son of a Roman soldier but was not a soldier himself8. Based on the nature of the relief, art historians thought that the person depicted on the tombstone wore military clothing and a mustache, and therefore must be considered a soldier9. Both opinions in each case were formulated only in the abstract and were not supported by detailed evidence. Obviously, only one of these versions can be true. To answer the question whether Aurelius Viator was a soldier, it is necessary to examine the pros and cons in more detail, as well as to pay attention to details that have not previously been used to solve the problem.

9. Maksimova, Nalivkina 1955, 319–320, рис. 36; Ivanova et al. 1976, 126, № 391; Chubova et al. 2008, 121; Doroshko 2012, 111.

The whole appearance persuades proponents of the buried soldier's status of the character. The clothing of Aurelius Viator indeed resembles that of a soldier. Each of the three elements depicted – tunic, cloak, and sandals – are part of the list of the Roman soldier10. However, the soldier's tunic and cloak themselves were in no way different from the clothing of wealthy citizens11. The Roman army did not have a uniform in the modern sense. Their military equipment determined visual identification of soldiers12. In the surviving pictorial monuments of the first centuries A.D., in the absence of weapons, the only signs that we are dealing with a soldier are a military belt and military sandals.

11. Sander 1963, 148; Hoss 2012, 29.

12. Bishop, Coulston 1993, 196.

We can find the confirmation in written sources. Petronius (Satir. 82) describes the remarkable adventure of Encolpius, who conceived, disguised as a soldier, to take revenge. For this purpose, the jealous man put on a belt and sword, but on the way, he was unmasked because of the Greek sandals on his feet. The Roman military open shoes (caligae) were a type of sandals characterized by a thick sole lined with many iron nails13. The author of the tomb of Aurelius Viator paid considerable attention to the depiction of the shoes. The straps covering the instep of the foot and ankle are shown. The longitudinal lace pulling the straps from the sole is visible. The thick sole draws it`s attention. But we have to admit that regardless of the sculptor's intention to show military or civilian shoes, the relief does not show the main distinguishing detail – the iron nails on the sole14. Another obstacle to identifying the sandals of Aurelius Viator with the military caligae is that by the time of his life, the caligae were going out of use. Archaeological evidence suggests that heavy military sandals ceased in the first quarter of the second century A.D.15 From that time on, only calcei, shoes that completely covered the heel, foot, and toes, remained used by the Roman army.

14. Here is an example of a shoe with a similar cut: a child's sandal from Bordeaux (Coulon 1994, 70).

15. Bishop, Coulston 1993, 119; James 2004, 59.

A more important and unambiguous meaning is the depiction of the belt (balteus, cingulum) on soldiers' tombstones and other images of soldiers16. Two types of Roman military portrait tombstones were most popular during the Empire period. The first type depicted soldiers in full armor. The second type showed soldiers dressed in a belted tunic and cloak17. The belt was the attribute that unmistakably distinguished soldiers from civilians; the sword depicted was not mandatory, although it was common. Examples of the tombstone steles depicting belts and weapons are numerous18. The tombstones of Aurelius Sylvanus and Marcus Mecilius can serve as such examples in Chersonesos19. In contrast to the above-mentioned examples, the portrait of Aurelius Viator is deprived of the belt. This is a fundamental argument against the possible soldier status of Aurelius.

17. Speidel 2012, 1–4.

18. Coulston 1987, 141–146; Bishop, Coulston 1993, 125, fig. 85; James 2004, 61, fig. 24, 25; Ďurianová 2011, 49–55; Papagianni 2013, 800.

19. Solomonik 1983, 58–61, No 31, 33.

Of course, the close connection between Aurelius Viator and the Roman garrison of the city cannot be denied. His name and epitaph language eloquently testify to it. All Latin inscriptions in Chersonesos are connected with Roman servicemen or their families. For this reason, we can conclude with a high probability that Aurelius' father was a serviceman or a veteran of the Roman army. There is also evidence that the section of the necropolis near the Southern city walls where the stele was found was used in the 3rd century AD for burials of Roman soldiers and officers. Also, in 1892, two graves of soldiers were discovered near the stele20.

The portrait's notable details can be pointed out as one of the arguments in favor of Aurelius' soldierly status. Some scholars have suggested that he has a mustache on his face21, i.e., he is an adult. This view is controversial. In general, the portrait is a vivid example of the so-called provincial-Roman style. The flat relief is far from a realistic image. Certain details of the portrait are difficult to interpret unambiguously. Thus, in my opinion, the nasolabial folds were taken as the image of a mustache, which is conveyed by two dee sharp furrows.

It is striking that the carver provided the figure with a disproportionately large head. Many researchers of the monument paid attention to this feature, describing it as follows: "a disproportionately short male figure"22; "the small figure of the deceased with a clearly outlined outline and an almost geometrically correct construction is completely disproportionate"23; "the depiction of the male figure... with gross disproportion (an inordinately large head and a short torso),24" "shortened body proportions.25" Distortion of proportions is the norm for the fine art of late Roman times. Nevertheless, such detail may not be accidental. In Roman art, children were depicted in this way, with a somewhat enlarged head26.

23. Maksimova, Nalivkina 1955, 319, 320.

24. Solomonik 1983, 68.

25. Zubar’ 2004, 466.

26. Minten 2000–2001, 75.

One element of the image has not previously been considered an argument in discussing whether Aurelius Viator was a soldier or not. It seems that it is the depiction of objects in his hands that finally resolves the issue of the interpretation of the character. The dead man holds a bird in his right hand and a large fruit (a grape or a cone) in his left hand. The bird in the hands of Aurelius Viator is his pet: a songbird or a pigeon. In particular, domestic animals and birds were an understandable symbol of childhood for contemporaries in antiquity. Like children today, boys and girls growing up in Roman cities kept pets and cared for their pets. This activity, along with games, was a favorite childhood activity and an important aspect of upbringing27.

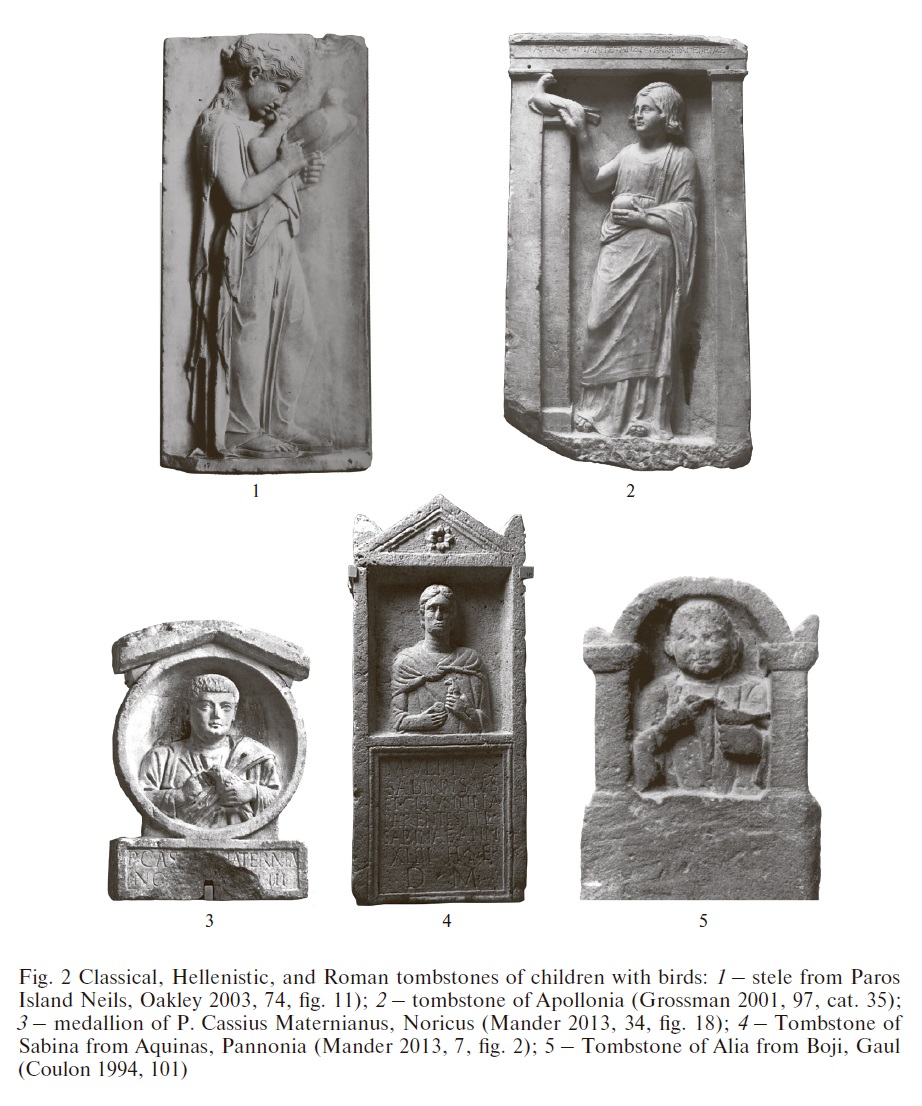

This attribute of childhood became a symbolic indication of age on images as early as classical Greece. Tombstones representing a single child figure appeared in Asia Minor and on the Aegean Islands28. The most famous stele found on Paros is the most heartfelt and highly artistic depiction of a child in ancient art29 (Fig. 2, 1). The motif of children holding birds is often found on tombstones in Attica30. In the Hellenistic era, this type of tombs continued to be popular3231 (Fig. 2, 2).

29. Oakley 2003, 180, 181; Beaumont 2003, 74, fig. 11.

30. Grossman 2001, 12; no. 3; Neils, Oakley 2003, 307, 308; cat. no.125; Grossman 2013, 91–92; no. 42; Margariti 2017, V, IX, XI, cat. no. E 6, E 12, E 15, E 25, E 26, E 41, E 68, E 82, E 88.

31. Vorster 1983, 331, 332, 338, 339, 342, 348–350, 353, 356, 364, Taf. 12, 1–3; 14, 2; 16, 1–3; 17, 3; 18, 3; 20, 2; 23, 1; Spiliopoulou-Donderer 1990; Grossman 2001, 69, 95, 96; no. 24, 35; Oakley 2003, 189; cat. no.126.

During the Roman Empire, the tradition spread throughout the provinces. As an illustration of this tradition, J. Mander calculated a large selection of Roman tombstones depicting children. On 174 tombstones, we see children with domestic animals32. Children's tombstones are known to depict the deceased accompanied with rabbits, dogs, and cats33. However, the most beloved character was the pet bird34. For the Imperial period, at least 118 tombstones with children and birds are known35 (Fig. 2, 3–5). The same tradition existed in the Middle East. On the burial reliefs of Palmyra, children were often depicted with birds and grapes in their hands36.

33. Vorster 1983, 360, 361, 371, 372, Taf. 18, 1; 20, 1, 3; 21, 1; Huskinson 1996, pl. 10, 2; Johns 2003, 54–60, fig. 1; Grossman 2001, 18–20; no. 5.

34. Pfuhl, Möbius 1979, 510, 522, 523, 528, Kat. Nr. 2112, 2187–2192; Taf. 304, 2112; 312, 2190–2192; Wujewski 1991, 45, pl. 57; Ortiz 1993, no. 242; Coulon 1994, 99–105; Huskinson 1996, 39, pl. 1, 3; Mesihović 2011, 50–52; Grossman 2013, 205, 207, no. 342, 347.

35. Mаnder 2013, 37, fig. 19, 20, tab. 5.

36. Parlasca 1990, 137, 142, Abb. 1, 16; Heyn 2010, 639, fig. 7; See also the reliefs from the Hermitage collection: inv. no. DV-4176; DV-4177.

It is noteworthy that this tradition, which is Greek in origin, made its way into Chersonesos in the 2nd and 3rd centuries as a part of provincial-Roman culture through the mediation of Roman garrison servicemen. This portrait of Aurelius Viator in Chersonesos is not the only one that depicts a child with a bird. There are two more tombstones of the same series. One of them is a portrait marble insert in tombstone with Latin inscription, which survived partially (Fig. 1, 2). The relief depicts a bird in the left hand of the character and round fruit, held in the right hand close to the bird's beak. Below the Latin inscription is carved as follows: "To the gods Manes. ...Sabinus, soldier..., to son Sabinus... put37. The authors of Chersonesos sculpture vault considered the depicted man to be a soldier38. The inscription follows that the soldier was the father of the deceased, who was also named Sabinus. The situation when both father and son were soldiers at the same time is unlikely. It is much more plausible to assume that Sabinus junior was a child39. This is convinced not only by the inscription text but also by the familiar attributes in his hands.

38. Ivanova et al. 1976, 127, № 394.

39. Solomonik 1983, 60.

The second anepigraphic limestone tombstone is completely preserved, but its surface is heavily weathered40 (Fig. 1, 3). Nevertheless, the nature of the portrait suggests that the person depicted on it is still very young. In his left hand, we can see a bird. We can see an object in the right hand, which, by analogy with the portraits of Aurelius Viator and Sabinus, can be considered a fruit. The listed tombstones date from the 2nd–3rd centuries A.D. All three images are not symbolic but quite realistic portraits of adolescents with animals represented in the same manner. These birds were the pets of young Chersonesos inhabitants who never got a chance to grow up.

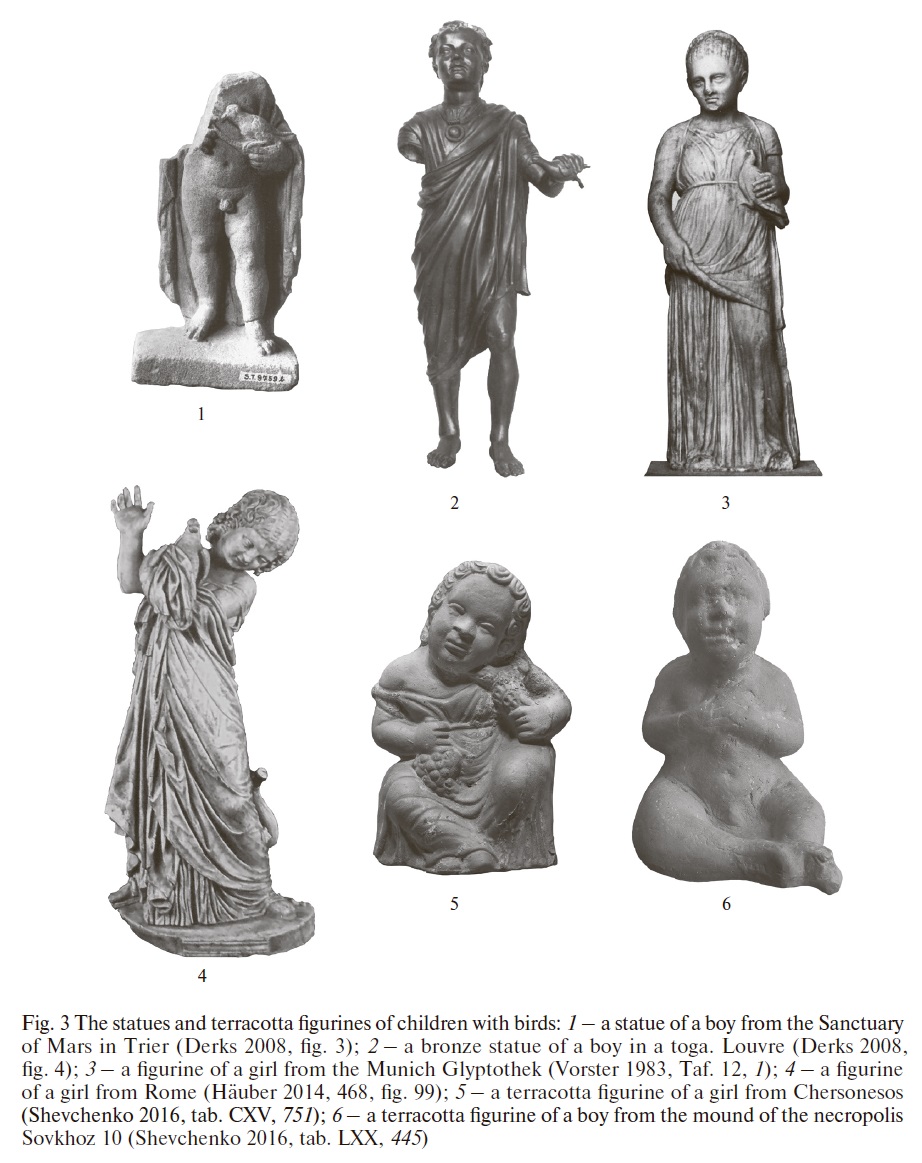

The burial portraits preserved the examples of images of children together with domestic animals. In red-figure paintings, playing with pets is one of the usual children's activities41. In stone sculpture, birds and puppies, with which children were often depicted, are known in Classical, Hellenistic, and Roman times 42(Fig. 3, 3, 4). G.D. Belov, who published a marble statue of Eros with a bird from Chersonesos, pointed to a big group of marble statuettes in the Hermitage collection showing boys with birds43. Findings from the Mars Sanctuary in Trier play an important role in understanding the significance of these sculptures. In inscriptions from there the deity is accompanied by Mars Iovantucarus, i.e. "the one who loves youth". During the excavations of the sanctuary, a series of statues of boys holding birds was found (Fig. 3, 1). These sculptures in the sanctuary were dedications of parents by vow44.

42. Havé-Nikolaus 1998, 179–181, Kat. Nr. 48, Taf. 1, 2; Beaumont 2003, 77–79, fig. 14, 15, 17; Häuber 2014, 585, 586, fig. 99.

43. Belov 1959, 22, 23, fig. 8.

44. Faust, Kuhnen 1996, 186–188, Kat. Nr. 33a–b; Derks 2008, 194.

Toreutics also provides examples of such representations: the bronze statue of a boy in a toga and holding a bird in his hand from the Louvre45 (fig. 3, 2); a bronze figure of Eros holding a bunch of grapes and a bird decorated a chariot from Mauretania46; the Metropolitan Museum has a statuette of a girl playing with a puppy47.

46. Boube-Piccot 1980, 283, no. 494.

47. Richter 1915, 160, 161, fig. 375.

Scenes of various children's games are present on the funerary stelai48. The most varied are the game scenes on a series of children's sarcophagi from various museums in Europe. Among the plots are playing with nuts, quackery, rolling a hoop, etc.49 These activities are indulged in by young children, while images of domestic animals most often accompany portraits of adolescents. As an illustration of this tradition, J. Haskinson notes that one of the explanations for this is a symbolic reference to the localization of the portrait in a domestic, private setting. At the same time, some images are quite realistic50.

49. Huskinson 1996, 16, 17.

50. Huskinson 1996, 88, cat. no. 1, 46, 47, 49; 5, 15; 8, 22, 26; 9, 43.

Coroplast gives many examples of depictions of children accompanied by domestic animals. Some terracotta figurines were obviously cheaper versions of offerings, copying stone and bronze statues. As such, terracottas depicting children with birds in their hands may have been used as gifts of parents as a thank-you for divine protection in the sanctuaries of gods, patrons of childhood51.

Terracotta images of children with birds and animals appear in the Northern Black Sea region not earlier than the middle of 2nd century B.C.52 In the necropolis of Kepoi in Bosporus, in burial 3 of barrow 17 was found 19 terracottas, among them, there are images of a boy with a goose, a boy with a doe, and a girl with a dog. The burial dates from the middle to the end of the 2nd century B.C.53 Bosporan statuettes depicting children and dogs as well as children and geese are collected in the work of A.A. Zavoikin54. In the context of burials and sanctuaries, such genre terracottas are often interpreted as images of gods in infancy or adolescence accompanied by animals with a symbolic essence (most often chthonic)55. Such a conclusion is difficult to dispute when the terracottas come from burials where every item of burial inventory is in one way or another associated with representations of the afterlife. Still, let us note that the plots of terracottas with children playing with or feeding animals were suggested by life56. Undoubtedly, some of the figurines of children accompanied by pets represent humans rather than gods.

53. Usacheva 1983, 80, fig. 2, 11–13, 15; Zhuravlev, et al. 2006, 28, 35, 36, рис. 15, 1–3.

54. Zavoykin 2006.

55. Zavoykin 2006, 160, 161.

56. Many of the terracottas clearly depict genre scenes. For example, children watching cockfights: Neils, Oakley 2003, 282, cat. no. 94.

We can find examples of similar terracotta figurines in Chersonesos. A figurine of a little girl holding a bird and a bunch of grapes was found in tomb 101357 (Fig. 3, 5). Another complete figurine showing a boy with a bird (Fig. 3, 6) was found in the mound of necropolis Sovkhoz 10 in the nearby area of Chersonesos58. Several fragmented terracottas from Chersonesos could also depict children, but their incomplete preservation makes it difficult to be certain59.

58. Strzheletskiy et al. 2003–2004, 175, fig. 33, Shevchenko 2016, 80, cat. No 445.

59. Shevchenko 2016, 59, 104, 136, 137, cat. No 286, 287, 633, 878.

The above examples of images of children with birds leave no doubt that the portrait tombstone of Aurelius Viator depicts a child, most likely a teenager. This raises the question of why his clothing is so similar to that of a soldier. The answer can be found if we take into account a tradition which was quite widespread in the Roman army. The single portrait was not the only tombstone relief, and often many relatives were represented on the monument. Many tombstones depicted fathers along with their children. On such tombstones, there are numerous examples of depictions of sons with clothes, hairstyle, and facial features that repeat the appearance of their fathers. As an illustration of this tradition, J. Mander gives the tombstone of Aurelius Beatus, trumpeter of the Second Auxiliary Legion found at Aquincum. Aurelia Quintilila erected the monument to her husband, who died in battle, and her son Vitalinus, who lived for 4 years, 11 months, and 18 days. The monument shows Vitalinus next to his father. The image of the son is identical to the figure of Aurelius Beat in such details as face, hairstyle, pose, and military clothes60.

The clothing of soldiers' sons imitated the appearance of their fathers not only in the fine arts but also in real life. To be convinced of this, it is enough to recall the famous explanation of the nickname of Gaius Caesar given by Suetonius in his biography (Cal. 9): "He owed his nickname "Caligula" to a camp joke, because he grew up among soldiers, dressed as a common soldier". The soldierly appearance of Aurelius Viator is an example of such traditions spreaded in a near-army environment. The young man was likely waiting for a military career, and the burial portrait conveys the image which the soldier's father wanted to depict: a child from a wealthy family, standing out by his clothing against the background of ordinary Greek Chersonesos inhabitants, following in his father's footsteps, a future soldier. This interpretation even explains the possible presence of a moustache in the portrait.

In my opinion, the degree of the symbolism of the images on the portrait tombstones of Chersonesos should not be exaggerated. In a certain sense, of course, both the gravestone itself and the subjects depicted on it are symbolic. Still, if we deal with a portrait, this symbolism should hardly be considered deeper than replacing an authentic image or object with its artistic embodiment. The idea of finding deep symbolism in portraits of children with birds pecking fruit is directly contradicted by the fact that we know no such portraits of adults. If the bird were understood as a symbol of the soul61 or initiation into some spiritual knowledge62, it would be impossible to explain why birds appear only in depictions of children. We cannot seriously assume that adults were perceived as spiritless beings or that the soul of adults took some other (non-bird) form.

62. Wujewski 1991, 45, 50.

A telling analogy to the degree of the symbolism of the three children's portrait tombstones with birds is the well-known group of burial stele from the 4th–3rd centuries BC from Chersonesos. In addition to the names, they contain concise symbols indicating the gender and age of the entombed people. Thus, the staffs clearly indicate the advanced age of the entombed. The swords on the porticoes indicate citizen warriors in the prime of life, the strigils and grease pans belong to young men engaged in gymnastic exercises and preparing for adulthood63. The staffs, swords, and strigils are symbolic in the same way as the pets of Aurelius Viator and Sabinus: they figuratively indicate the typical occupation of a person at a certain age64, i.e., they are intended to emphasize the social position of the entombed person.

64. Sokolov 2000, 320, 371.

As mentioned above, the bird in hand was not the only pet option when depicting a child. Portraits of children with dogs, rabbits, cats, and horses were also common in Roman provinces. The variety of animals65 indicates that there was no strict canon for the depiction and the choice of animal probably depended on the preferences of the child himself. From this point of view, it was important to indicate a pet for the customers of the tombstones, and the choice of a particular animal was not so crucial. If this reasoning is correct, then we are a direct reflection of the preferences of the young population of Roman cities. Judging by the greater popularity of children's portraits accompanied by birds, it was keeping feathered pets that children paid the most attention to.

V.I. Kadeev characterizes the daily activities of children in the city as follows: "It is likely that little Chersonesos inhabitants rode on a stick, played blindman's buff and with pets, bowled a hoop like their mates from other ancient Greek cities, but, unfortunately, we have no direct evidence of this.66" I believe that the three children's burial portraits discussed in this article may well be considered as such evidence. What was theoretically known about children's daily routines in Chersonesos is now given a form of evidence, supported by facts: children played with their pets in the streets and courtyards of Chersonesos, cages with singing birds were in children's rooms, and pigeon-houses completed the image of the city above the roofs of the houses.

Библиография

- 1. Beaumont, L.A. 2003: The changing face of childhood. In: J. Neils, J.H. Oakley (eds.), Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past. New Haven–London, 59–83.

- 2. Belov, G.D. 1959: [Report on the excavations in Chersonese in 1955]. Khersonesskiy sbornik [Chersonesus Collected Articles] 5, 13–69.

- 3. Bishop, M.C., Coulston, J.C.N. 1993: Roman Military Equipment from the Punic Wars to the Fall of Rome. London.

- 4. Boube-Piccot, Chr. 1980: Les bronzes antiques du Maroc. III: Les chars et l’attelage. Rabat.

- 5. Bradley, K. 1998: The sentimental education of the Roman child: the role of pet-keeping. Latomus 57/3, 523–557.

- 6. Chubova, A.P., Kolesnikova, L.G., Fedorov, B.N. 2008: Arkhitektura i iskusstvo Khersonesa Tavricheskogo. V v. do n.e. – IV v. n.e. [Architecture and Art of Tauric Chersonese. 5th Cent. BC – 4th Cent. AD]. Moscow.

- 7. Colling, D. 2011: Les scènes de banquet funéraire ou Totenmahlreliefs originaires d’Arlon. Bulletin trimestriel de l’Institut Archéologique du Luxembourg 87/4, 155–176.

- 8. Coulon, G. 1994: L’Enfant en Gaule romaine. Paris.

- 9. Coulston, J.C. 1987: Roman military equipment on third century tomb-stones. In: M. Dowson (ed.), Roman Military Equipment: The Accoutrements of War. Proceedings of the Third Roman Military Equipment Seminar, Nottingham 1985. Oxford, 141–156.

- 10. Danilenko, V.N. 1969: [Grave steles]. Soobshcheniya Khersonesskogo muzeya [Reports of The Chersonese Museum] 4, 29–44.

- 11. Derks, T. 2008: Les rites de passage et leur manifestation matérielle dans les sanctuaires des Trévires. In: D. Castella, M.-F. Meylan Krause (eds.), Topographie sacrée et rituels: Le cas d’Aventicum, capitale des Helvètes. Actes du colloque international d’Avenches, 2–4 novembre 2006. Basel, 191–204.

- 12. Doroshko, V.V. 2012: [Roman military footwear from the excavations of Chersonese and its surroundings]. In: D.V. Zhuravlev, K.B. Firsov (eds.), Evraziya v skifo-sarmatskoe vremya. Pamyati Iriny Ivanovny Gushchinoy [Eurasia in the Scythian and Sarmatian Time. In Memory of Irina Ivanovna Gushchina]. Moscow, 100–113.

- 13. Doroshko, V.V., Zhuravlev, D.V. 2018: [Two graves of Roman soldiers from the necropolis of Chersonesos Taurica]. Vestnik drevney istorii [Journal of Ancient History] 78/2, 349–364.

- 14. Ďurianová, A. 2011: Darstellungen von Soldaten und militärischen Dienern auf pannonischen Steindenkmälern. In: M. Verčik (ed.), Rüstung und Waffen in der Antike. Trnava, 35–69.

- 15. Faust, S., Kuhnen, H.-P. 1996: Religio Romana: Wege zu den Göttern im antiken Trier. Trier.

- 16. Grossman, J.B. 2001: Greek Funerary Sculpture: Catalogue of the Collections at the Getty Villa. Los Angeles.

- 17. Grossman, J.B. 2013: Funerary Sculpture. (The Athenian Agora, 35). Princeton.

- 18. Häuber, C. 2014: The Eastern Part of the Mons Oppius in Rome: The Sanctuary of Isis et Serapis in Regio III, the Temples of Minerva Medica, Fortuna Virgo and Dea Syria, and the Horti of Maecenas. Roma.

- 19. Havé-Nikolaus, F. 1998: Untersuchungen zu den kaiserzeitlichen Togastatuen griechischer Provenienz. Kaiserliche und private Togati der Provinzen Achaia, Creta (et Cyrene) und Teilen der Provinz Macedonia. Mainz am Rhein.

- 20. Heyn, M.K. 2010: Gesture and identity in the funerary art of Palmyra. American Journal of Archaeology 114/4, 631–661.

- 21. Hoorn, G. van. 1951: Choes and Anthesteria. Leiden.

- 22. Hoss, S. 2012: The Roman military belt. In: M.-L. Nosch (ed.), Wearing the Cloak: Dressing the Soldier in Roman Times. Oxford–Oakville, 29–44.

- 23. Huskinson, J. 1996: Roman Children’s Sarcophagi: Their Decoration and Its Social Significance. Oxford.

- 24. Ivanova, A.P., Chubova, A.P., Kolesnikova, L.G. 1976: Antichnaya skul’ptura Khersonesa: Katalog [Antique Sculpture of Chersonese: Catalog]. Kiev.

- 25. James, S. 2004: The Excavations at Dura-Europos conducted by Yale University and the French Academy of Inscriptions and Letters 1928 to 1937. Final Report VII. The Arms and Armour and Other Military Equipment. London.

- 26. Johns, C. 2003: The tombstone of Laetus’ daughter: cats in Gallo-Roman sculpture. Britannia 34, 53–63.

- 27. Kadeev, V.I. 1996: Khersones Tavricheskiy. Byt i kul’tura (I–III vv. n.e.) [Tauric Chersonese. Way of Life and Culture (I–III Cent. AD)]. Khar’kov.

- 28. Kostromichev, D.A. 2016: [Was Aurelius Viator a soldier? One aspect of children’s subculture in Chersonese]. In: Uvarovskie Tavricheskie cht-eniya «Drevnosti Yuga Rossii». Tezisy dokladov i soobshcheniy Mezhdunarodnoy nauchnoy konferentsii [Uvarov Taurida Readings “Antiquities of South Russia”. Abstracts and Reports of the International Scientific Conference]. Sevastopol’, 27–29.

- 29. Kosciuszko-Walużynicz, K.K. 1894: [Enumeration of antiquities found in 1892 in a burial ground near the southern city wall of Chersonese]. Otchet Imperatorskoy arkheologicheskoy komissii za 1892 g. [Report of Imperial Archaeological Commission for 1892], 101–123.

- 30. Latyshev, V.V. 1895: Grecheskie i latinskie nadpisi, naydennye v yuzhnoy Rossii v 1892–1894 gg. [Greek and Latin Inscriptions Found in South-ern Russia in 1892–1894]. Saint Petersburg.

- 31. Maksimova, M.I., Nalivkina, M.A. 1955: [Sculpture]. In: V.F. Gaydukevich, M.I. Maksimova (eds.), Antichnye goroda Severnogo Prichernomor’ya: ocherki istorii i kul'tury [Ancient Cities of the Northern Black Sea Region: Essays on History and Culture]. Moscow–Leningrad, 297–324.

- 32. Mander, J. 2013: Portraits of Сhildren on Roman Funerary Monuments. Cambridge.

- 33. Margariti, K. 2017: The Death of the Maiden in Classical Athens. Oxford.

- 34. Mesihović, S. 2011: Antiqvi homines Bosnae. Sarajevo.

- 35. Minten, E. 2000–2001: Roman children and their pets: a socio-iconographical survey. Opuscula Romana 25–26, 73–77.

- 36. Neils, J., Oakley, J.H. 2003: Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past. New Haven–London.

- 37. Nikolaeva, E.Ya. 1974: [Terracotta from the city of Kepoi]. In: M.M. Kobylina (ed.), Terrakotovye statuetki. Ch. 4: Pridon’e i Tamanskiy poluostrov [Terracotta Figurines. Pt. 4: Don Region and Taman Peninsula]. Moscow, 13–15.

- 38. Oakley, J.H. 2003: Death and the child. In: J. Neils, J.H. Oakley (eds.), Coming of Age in Ancient Greece: Images of Childhood from the Classical Past. New Haven–London, 163–194.

- 39. Ortiz, G. 1993: The George Ortiz Collection. Antiquities from Ur to Byzantium. Berne.

- 40. Paetz gen. Schieck, A., 2012: A late Roman painting of an Egyptian officer and the layers of its perception. On the relation between images and textile finds. In: M.-L. Nosch (ed.), Wearing the Cloak: Dressing the Soldier in Roman Times. Oxford–Oakville, 85–108.

- 41. Papagianni, E. 2013: Grabreliefs römischer Soldaten aus Griechenland: Beobachtungen zu ihrer Typologie und Ikonographie. In: N. Cambi, G. Koch (eds.), Funerary Sculpture of the Western Illyricum and Neigh-bouring Regions of the Roman Empire: Proceedings of the International Scholarly Conference held in Split from September 27th to the 30th 2009. Split, 795–814.

- 42. Parlasca, K. 1990: Palmyrenische Skulpturen in Museen an der amerikanischen Westküste. In: M. True, G. Koch (eds.), Roman Funerary Mon-uments in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Vol. 1. Malibu, 133–144.

- 43. Pfuhl, E., Möbius, H. 1979: Die ostgriechischen Grabreliefs. Textband 2. Mainz.

- 44. Posamentir, R. 2011: The Polychrome Grave Stelai from the Early Hellenistic Necropolis. (Chersonesan Studies, 1). Austin.

- 45. Richter, G.M.A. 1915: Greek, Etruscan and Roman Bronzes. New York.

- 46. Sander, E. 1963: Die Kleidung des römischen Soldaten. Historia: Zeitschrift für Alte Geschichte 12, 144–166.

- 47. Shevchenko, A.V. 2016: Terrakoty antichnogo Khersonesa i ego blizhney sel’skoy okrugi [Terracotta of Ancient Chersonese and Its Near Rural Neighborhood]. Simferopol’.

- 48. Sokolov, G.I. 2000: Ol’viya i Khersones (ionicheskoe i doricheskoe iskusstvo) [Olbia and Chersonese (Ionic and Doric Art)]. Moscow.

- 49. Solomonik, E.I. 1983: Latinskie nadpisi Khersonesa Tavricheskogo [Latin Inscriptions of Tauric Chersonese]. Moscow.

- 50. Spiliopoulou-Donderer, I. 1990: Das Grabrelief der Apollonia im J. Paul Getty Museum. In: M. True, G. Koch (eds.), Roman Funerary Monu-ments in the J. Paul Getty Museum. Vol. 1. Malibu, 5–14.

- 51. Speidel, M. 2012: Dressed for the occasion. clothes and context in the Roman army. In: M.-L. Nosch (ed.), Wearing the Cloak: Dressing the Sol-dier in Roman Times. Oxford–Oakville, 1–12.

- 52. Strzheletskiy, S.F., Vysotskaya, T.N., Ryzhova, L.Yu., Zhestkova, G.I. 2003–2004: [The population in the neighborhood of Chersonesos Tauricus in the first half of the first millennium AD (by materials of the necropolis “Sovkhoz No. 10”)]. Stratum plus 4, 27–277.

- 53. Стржелецкий, С.Ф., Высотская, Т.Н., Рыжова, Л.Ю., Жесткова, Г.И. Население округи Херсонеса в первой половине I тысячелетия новой эры (по материалам некрополя «Совхоз № 10»). Stratum plus 4, 27–277.

- 54. Usacheva, O.N. 1983: [Terracotta figurines from the burial mound near Kepoi]. Kratkie soobshcheniya Instituta arkheologii [Brief Communica-tions of the Institute of Archaeology] 174, 77–82.

- 55. Vorster, C. 1983: Griechische Kinderstatuen. Köln.

- 56. Woods, D. 1993: The ownership and disposal of military equipment in the late Roman army. Journal of Roman Military Equipment Studies 4, 55–65.

- 57. Wujewski, T. 1991: Anatolian Sepulchral Stelae in Roman Times. Poznan.

- 58. Zavoykin, A.A. 2006: [Two subjects in the terracotta complex at the sanctuary of Eleusinian goddesses (Beregovoi 4)]. In: D.V. Zhuravlev (ed.), Severnoe Prichernomor’e v epokhu antichnosti i srednevekov’ya [Northern Black Sea Region in Antiquity and the Middle Ages]. Moscow, 158–168.

- 59. Zhuravlev, D.V. 1997: [Collections from Chersonese in the State Historical Museum]. Vestnik drevney istorii [Journal of Ancient History] 3, 194–207.

- 60. Zhuravlev, D.V. (ed.) 2002: Na krayu oykumeny. Greki i varvary na severnom beregu Ponta Evksinskogo [On the Edge of Ecumene. Greeks and Barbarians on the Northern Coast of the Pontus Euxinus]. Moscow.

- 61. Zhuravlev, D.V., Il’ina, T.A., Lomtadze, G.A., Sudarev, N.I. 2006: [Materials from burial mound of Kepoi necropolis: a burial mound 17 (18)]. In: D.V. Zhuravlev (ed.), Severnoe Prichernomor’e v epokhu antichnosti i srednevekov’ya [Northern Black Sea Region in Antiquity and the Middle Ages]. Moscow, 12–46.

- 62. Zubar’, V.M. 1994: Khersones Tavricheskiy i Rimskaya imperiya. Ocherki voenno-politicheskoy istorii [Tauric Chersonese and Roman Empire. Es-says on Military and Political History]. Kiev.

- 63. Zubar’, V.M. et al. (eds.) 2004: Khersones Tavricheskiy v seredine I v. do n.e. – VI v. n.e. Ocherki istorii i kul’tury [Tauric Chersonese in the Middle of the 1st Century BC – 6th Century AD. Essays on History and Culture]. Kharkov.

2. Zhuravlev 1997, 199, fig. 5, 1.

3. Latyshev 1895, 16, 17, No 15; IOSPE I2, 566; Solomonik 1983, 67, 68, No. 42; Zhuravlev 2002, 90, No 379.

4. Latyshev 1895, 16; Solomonik 1983, 68.